Lancelot-Grail

The work of unknown authorship, presenting itself as a chronicle of actual events, retells the legend of King Arthur by focusing on the love affair between Lancelot and Guinevere, the religious quest for the Holy Grail, and the life of Merlin.

Most prominently, they involve the Holy Grail, the vessel that contained the blood of Christ, which is searched for by many members of the Round Table until Lancelot's son Galahad ultimately emerges as the winner of this sacred journey.

Together, the two prose cycles with their abundance of characters and stories represent a major source of the legend of Arthur as they constituted the most widespread form of Arthurian literature of the late medieval period, during which they were both translated into multiple European languages and rewritten into alternative variants, including having been partially turned into verse.

They also inspired various later works of Arthurian romance, eventually contributing the most to the compilation Le Morte d'Arthur that formed the basis for a modern canon of Arthuriana that is still prevalent today.

[4] These characters are described as the scribes in service of Arthur who recorded the deeds of the Knights of the Round Table, including the grand Grail Quest, as relayed to them by the eyewitnesses of the events beings told in the story.

It is uncertain whether the medieval readers actually believed in the truthfulness of the centuries-old "chronicle" characterisation or if they recognised it as a contemporary work of creative fiction.

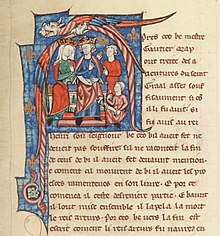

[5] Welsh writer Gautier (Walter) Map (c. 1140 – c. 1209) is attributed to be the editing author, as can be seen in the notes and illustrations in some manuscripts describing his discovery in an archive at Salisbury of the chronicle of Camelot, supposedly dating from the times of Arthur, and his translation of these documents from Latin to Old French as ordered by Henry II of England[6] (the location was changed from Salisbury to the mystical Avalon in a later Welsh redaction[7]).

There might have been either a single master-mind planner, the so-called "architect" (as first called so by Jean Frappier, who compared the process to building a cathedral[11]), who may have written the main section (Lancelot Proper), and then overseen the work of multiple other anonymous scribes.

[17] Today it is believed by some (such as editors of the Encyclopædia Britannica[18]) that a group of anonymous French Catholic monks wrote the cycle – or at least the Queste part (where, according to Fanni Bogdanow, the text's main purpose is to convince sinners to repent[19]).

[22] Richard Barber described the Cistercian theology of the Queste as unconventional and complex but subtle, noting its success in appealing to the courtly audience accustomed to more secular romances.

[23] The Lancelot-Grail Cycle may be divided into three[18] main branches, although more usually into five,[24] with the romances Queste and Mort regarded as separate from the Vulgate Lancelot (the latter possibly initially standalone in the original so-called "short version").

[28] The cycle has a narrative structure close to that of a modern novel in which multiple overlapping events featuring different characters may simultaneously develop in parallel and intertwine with each other through the technique known as interlace (French: entrelacement).

Set several centuries prior to the main story, it is derived from Robert de Boron's poem Joseph d'Arimathie [fr] with new characters and episodes added.

[37] It primarily deals with a series of episodes of Lancelot's early life and with the courtly love between him and Queen Guinevere, as well as his deep friendship with Galehaut, interlaced with the adventures of Gawain and other knights such as Yvain, Hector, Lionel, and Bors.

[17] The actual [Conte de la] Charrette ("[Tale of the] Cart"), an incorporation of a prose rendition of Chrétien's poem, spans only a small part of the Vulgate text.

[40][41][42][43] It was perhaps originally an independent romance that would begin with Lancelot's birth and finish with a happy ending for him, discovering his true identity and receiving a kiss from Guinevere when he confesses his love for her.

The Lancelot-Graal Project website lists (and links to the scans of many of them) close to 150 manuscripts in French,[50] some fragmentary, others, such as British Library Add MS 10292–10294, containing the entire cycle.

Perhaps because it was so vast, copies were made of parts of the legend which may have suited the tastes of certain patrons, with popular combinations containing only the tales of either Merlin or Lancelot.

[37][58] Along with the Prose Tristan, both the Post-Vulgate and the Vulgate original were among the most important sources for Thomas Malory's seminal English compilation of Arthurian legend, Le Morte d'Arthur (1470),[28][59] which has become a template for many modern works.