Eleanor of Aquitaine

Twelfth century Aquitaine was a relatively vast and somewhat ill-defined area of modern-day France, stretching from the Loire in the north to the Pyrenees in the south, and from the Atlantic to the west to the Massif Central to the east.

[56] Since kidnapping an heiress was seen as a viable option for obtaining a title and lands,[57] when William X knew that he was dying, he placed Eleanor in the care of King Louis VI of France as her guardian, since she would be orphaned.

The Pope, recalling similar attempts by William X to exile supporters of Innocent from Poitou and replace them with priests loyal to himself, may have blamed Eleanor for this,[78] but stated that Louis was only "a foolish schoolboy" and should be taught not to meddle in such matters.

[83] Both Theobald, who had taken his sister under protection, and Bernard of Clairvaux protested to the Pope, who convened a council, voided both the annulment from Countess Eleanor and marriage to Petronilla, excommunicated one bishop and suspended the other two.

For a year the royal army laid waste to the Champagne countryside, but since Theobald showed no signs of backing down, Louis took personal charge of the assault in 1143, which focused on the siege of the town of Vitry.

Noting a lack of enthusiasm among the French nobility, Louis postponed further action till Easter 1146, having recruited Bernard of Clairveaux to deliver a message supporting his crusade at Vézelay on 31 March.

There they were met by envoys from Manuel Komnenos (r. 1143–1180), the Byzantine Emperor,[99] and followed the river via Klosterneuburg and through Hungary, reaching Belgrade and the Eastern Empire by mid-August and then, crossing the Danube, to Adrianople and finally Constantinople, five days later, on 4 October 1147.

On the day of their crossing of Mount Cadmus, Louis took charge of the rear of the column, where the unarmed pilgrims and the baggage trains were, while the vanguard was commanded by the Aquitainian, Geoffrey de Rancon, and instructed to set camp on the plateau before the next pass.

They reached the summit of Cadmus, one of the highest in their path, but Rancon, in concert with Louis's uncle Amadeus III, Count of Savoy and Maurienne,[n] chose to continue on through the pass to the next valley, judging it a better campsite.

"[106][107][104] The chronicler William of Tyre, writing between 1170 and 1184 and thus perhaps too long after the event to be considered historically accurate, placed the blame for this disaster firmly on the amount of baggage being carried, much of it reputedly belonging to Eleanor and her ladies, and the presence of non-combatants.

[p][114][94] At King Roger's court in Potenza, Eleanor had learned of the death of her uncle Raymond, who had been beheaded by Nureddin's (Nur ad-Din) Muslim forces at the Battle of Inab, on 29 June.

[117][118] From Tusculum, the couple travelled north through Italy, visiting Rome and then crossing the Alps to reach France and finally arriving in Paris around 11 November 1149, after an absence of two and a half years.

Chroniclers such as Giraldus Cambrensis (Gerald of Wales), William of Newburgh and Walter Map later implied that something happened between Henry and Eleanor, eleven years his senior, that contributed to the dissolution of her marriage with Louis.

[124] Any such dissolution would require a complex political realignment, separating the Aquitanian and Capetian possessions and jurisdictions, and in the autumn of 1151 the couple made a tour of the duchy during which much of the French presence, such as garrisons, was replaced with Eleanor's people.

[127][77] On 21 March, the four archbishops, with the approval of Pope Eugenius, granted an annulment on grounds of consanguinity within the fourth degree; Eleanor was Louis's third cousin once removed, and shared common ancestry with Robert II of France and his wife Constance of Arles.

[145] Within a month, Henry departed with the intention of pursuing his claim to the throne of England[z] but now had to deal with Louis's invasion of Normandy, which he easily repelled within six weeks,[146] signing a truce, so that by the autumn of that year he was able to return to Aquitaine.

[156][157] Relatively little is known about Eleanor during the reign of Henry II, in that the chroniclers barely mention her, other than to note when she was with the King, and biographies have been built on these itineraries and surviving official documents, including letters,[158] writs and charters.

Geoffrey was betrothed to Constance of Brittany[194] and negotiations were begun to marry Joanna to King William II of Sicily[196] and John to Alicia, eldest daughter of Humbert III, Count of Savoy.

[195] From Paris, William of Newburgh recounts, "the younger Henry, devising evil against his father from every side by the advice of the French king, went secretly into Aquitaine where his two youthful brothers, Richard and Geoffrey, were living with their mother, and with her connivance, so it is said, he incited them to join him.

[an][229][230] Gerald of Wales states that Henry considered having his marriage annulled on the grounds of consanguinity during 1175, requesting a visit from a papal legate to discuss the matter further, and meeting with Cardinal Pierlone at Winchester on 1 November, who dissuaded him from this course.

[234] While Eleanor remained confined, she was not strictly a prisoner, but rather in a form of "house arrest" although stripped of her revenues, and in the later part of this period enjoyed some greater freedoms from 1177 onwards and particularly after 1184, and would witness the death of two more of her sons (Henry and Geoffrey) and her daughter Matilda, but very little information exists about these years.

Her death would much later lead to myths concerning Eleanor's putative involvement[ao] that grew more elaborate over the centuries, and for a long time were accepted as established facts, further building her Black Legend, despite virtually no contemporary evidence to support this.

[53][236][193] Some chroniclers, including Gerald of Wales, Ralph Niger, Roger of Hoveden and Ranulf Higden state that Henry then began an affair with the sixteen-year-old Alys of France, a matter complicated by the fact that she was betrothed to his son Richard and was also the daughter of Louis VII, who became alarmed on hearing this news.

[260] On 2 February 1190, Eleanor joined Richard at the Chateau of Bures, Normandy, where he continued to make preparations, and a family conclave was held at Nonancourt with John in attendance at which arrangements for the administration of England in the King's absence were finalised.

It was during the spring of 1190 that negotiations began with the Navarrese House of Jiménez regarding Berengaria, daughter of Sancho VI of Navarre, though such an alliance would require the approval of Philip in breaking Richard's betrothal.

[274][255] In the Holy Land, Richard made little progress in his quest to capture Jerusalem, and by late 1192 was forced to arrange a truce with Saladin, and sent Joanna and Berengaria back to Sicily in September, departing from Acre himself on 9 October.

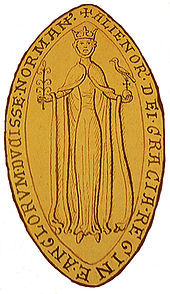

Some romanesque carvings, such as those at the Cloisters in New York and Chartres[331] and Bordeaux cathedrals have been attributed to her but these cannot be substantiated,[319][317][326] while completely erroneous claims from medieval art have frequently been used to illustrate articles and books about her, such as a queen from the 14th century Codex Manesse.

[374] Eleanor of Aquitaine is thought to be the chunegin von Engellant (Queen of England) mentioned in the 12th century poem "Were diu werlt alle min," in Carl Orff's Carmina Burana.

Flower and Hawk is a monodrama for soprano and orchestra, written by American composer Carlisle Floyd in 1972, in which Eleanor relives memories of her time as queen, and at the end hears the bells that toll for Henry's death, and in turn, her freedom.

Most of these were clerics, like William of Tyre, John of Salisbury, Mathew Paris, Helinand de Froidment and Aubri des Trois Fontaines and based their assessments on "the common talk of the day".

Louvre Museum