W. S. Gilbert

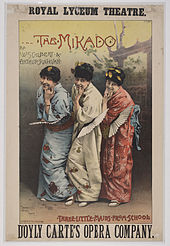

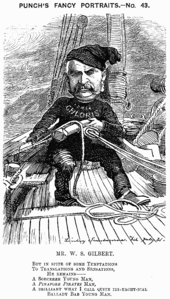

Sir William Schwenck Gilbert (18 November 1836 – 29 May 1911) was an English dramatist, librettist, poet and illustrator best known for his collaboration with composer Arthur Sullivan, which produced fourteen comic operas.

After brief careers as a government clerk and a lawyer, Gilbert began to focus, in the 1860s, on writing light verse, including his Bab Ballads, short stories, theatre reviews and illustrations, often for Fun magazine.

In 1859, he joined the Militia, a part-time volunteer force formed for the defence of Britain, which he served in until 1878 (in between writing and other work), reaching the rank of captain.

Written and rushed to the stage in 10 days, Dulcamara, or the Little Duck and the Great Quack, a burlesque of Gaetano Donizetti's L'elisir d'amore, proved extremely popular.

As Jessie Bond vividly described it, "stilted tragedy and vulgar farce were all the would-be playgoer had to choose from, and the theatre had become a place of evil repute to the righteous British householder.

[27] From 1869 to 1875, Gilbert joined with one of the leading figures in theatrical reform, Thomas German Reed (and his wife Priscilla), whose Gallery of Illustration sought to regain some of theatre's lost respectability by offering family entertainments in London.

[28] The environment of the German Reeds' intimate theatre allowed Gilbert quickly to develop a personal style and freedom to control all aspects of production, including set, costumes, direction and stage management.

[33] During this time, Gilbert perfected the 'topsy-turvy' style that he had been developing in his Bab Ballads, where the humour was derived by setting up a ridiculous premise and working out its logical consequences, however absurd.

Thus the Learned Judge marries the Plaintiff, the soldiers metamorphose into aesthetes, and so on, and nearly every opera is resolved by a deft moving of the goalposts ... His genius is to fuse opposites with an imperceptible sleight of hand, to blend the surreal with the real, and the caricature with the natural.

He collaborated with Gilbert Arthur à Beckett on The Happy Land (1873), a political satire (in part, a parody of his own The Wicked World), which was briefly banned because of its unflattering caricatures of Gladstone and his ministers.

[42] He sought realism in acting, settings, costumes, and movement, if not in content of his plays (although he did write a romantic comedy in the "naturalist" style, as a tribute to Robertson, Sweethearts).

[44] Robertson "introduced Gilbert both to the revolutionary notion of disciplined rehearsals and to mise-en-scène or unity of style in the whole presentation – direction, design, music, acting.

"[35] Gilbert prepared meticulously for each new work, making models of the stage, actors and set pieces, and designing every action and bit of business in advance.

Gilbert worked again with Clay on Happy Arcadia (1872), and with Alfred Cellier on Topsyturveydom (1874), as well as writing several farces, operetta libretti, extravaganzas, fairy comedies, adaptations from novels, translations from the French, and the dramas described above.

The story portrays some "innocent" Scottish rustics making a living by throwing trains off the lines and then charging the passengers for services and, in parallel, romance being gladly thrown over in favour of monetary gain.

A New York Times reviewer wrote in 1879, "Mr Gilbert, in his best work, has always shown a tendency to present improbabilities from a probable point of view, and in one sense, therefore, he can lay claim to originality; fortunately this merit in his case is supported by a really poetic imagination.

In [Engaged] the author gives full swing to his humor, and the result, although exceedingly ephemeral, is a very amusing combination of characters – or caricatures – and mock-heroic incidents.

After a dispute with Carte over the division of profits, the other Comedy Opera Company partners hired thugs to storm the theatre one night to steal the sets and costumes, intending to mount a rival production.

[82] In addition, Gilbert's political satire often poked fun at those in the circles of privilege, while Sullivan was eager to socialise among the wealthy and titled people who would become his friends and patrons.

"[86] The scholar Andrew Crowther has commented: After all, the carpet was only one of a number of disputed items, and the real issue lay not in the mere money value of these things, but in whether Carte could be trusted with the financial affairs of Gilbert and Sullivan.

Nevertheless, the partnership had been so profitable that, after the financial failure of the Royal English Opera House, Carte and his wife sought to reunite the author and composer.

[87] In 1891, after many failed attempts at reconciliation by the pair, Tom Chappell, the music publisher responsible for printing the Gilbert and Sullivan operas, stepped in to mediate between two of his most profitable artists, and within two weeks had succeeded.

[94] After casting Nancy McIntosh in Utopia, Limited, he and his wife developed an affection for her, and she eventually gained the status of an unofficially adopted daughter, moving to Grim's Dyke to live with them.

[95] A statue of Charles II, carved by Danish sculptor Caius Gabriel Cibber in 1681, was moved in 1875 from Soho Square to an island in the lake at Grim's Dyke, where it remained when Gilbert purchased the property.

Aware of this general impression, he claimed that "If you give me your attention",[114] the misanthrope's song from Princess Ida, was a satiric self-reference, saying: "I thought it my duty to live up to my reputation.

The neat articulation of incredibilities in Gilbert's plots is perfectly matched by his language ... His dialogue, with its primly mocking formality, satisfies both the ear and the intelligence.

His verses show an unequalled and very delicate gift for creating a comic effect by the contrast between poetic form and prosaic thought and wording ... How deliciously [his lines] prick the bubble of sentiment.

[129][130] Gilbert's lyrics employ punning, as well as complex internal and two and three-syllable rhyme schemes, and served as a model for such 20th century Broadway librettists and lyricists as P. G. Wodehouse,[131] Cole Porter,[132] Ira Gershwin,[133] Lorenz Hart and Oscar Hammerstein II.

[n 14] In addition, people continue to write biographies about Gilbert's life and career,[136] and his work is not only performed, but frequently parodied, pastiched, quoted and imitated in comedy routines, film, television and other popular media.

Its leading exponents lampoon and send up the major institutions and public figures of the day, wielding the weapon of grave and temperate irony with devastating effect, while themselves remaining firmly within the Establishment and displaying a deep underlying affection for the objects of their often merciless attacks.