WWVB

WWVB is a longwave time signal radio station near Fort Collins, Colorado and is operated by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

The normal signal transmitted from WWVB is 70 kW ERP and uses a 60 kHz carrier wave yielding a frequency uncertainty of less than 1 part in 1012.

[4] In 2011, NIST estimated the number of radio clocks and wristwatches equipped with a WWVB receiver at over 50 million.

[7] At midnight on April 7, 2024, WWVB's south antenna was disabled due to damage sustained during high winds.

On May 20, 2024, NIST announced that the necessary replacement parts were being manufactured and shipped, with expected service restoration at the end of September 2024.

As early as 1904, the United States Naval Observatory (USNO) was broadcasting time signals from the city of Boston as an aid to navigation.

This experiment and others like it made it evident that LF and VLF signals could cover a large area using a relatively low power.

By 1923, NIST radio station WWV had begun broadcasting standard carrier signals to the public on frequencies ranging from 75 to 2,000 kHz.

Over the years, many radio navigation systems were designed using stable time and frequency signals broadcast on the LF and VLF bands.

This site became the home of WWVB and WWVL, a 20 kHz station that was moved from the mountains west of Boulder.

As part of a WWVB modernization program in the late 1990s, the decommissioned WWVL antenna was refurbished and incorporated into the current phased array.

This resulted in the introduction of many new low-cost radio controlled clocks that "set themselves" to agree with NIST time.

WWVB's Colorado location makes the signal weakest on the U.S. east coast, where urban density also produces considerable interference.

[12] Use of 40 kHz would permit use of dual-frequency time code receivers already produced for the Japanese JJY transmitters.

Funding, which was allocated as part of the 2009 ARRA "stimulus bill", expired before the impasse could be resolved,[14] and it is now unlikely to be built.

This requires no additional transmitters or antennas, and phase modulation had already been used successfully by the German DCF77 and French TDF time signals.

Each consists of four 400-foot (122 m) towers that are used to suspend a "top-loaded monopole" (umbrella antenna), consisting of a diamond-shaped "web" of several cables in a horizontal plane (a capacitive "top-hat") supported by the towers, and a downlead (vertical cable) in the middle that connects the top-hat to a "helix house" on the ground.

The combination of the downlead and top-hat is designed to replace a single, quarter-wavelength antenna, which, at 60 kHz, would have to be an impractical 4,100 feet (1,250 m) tall.

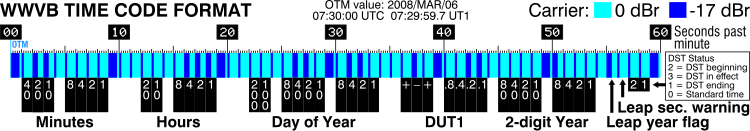

The other 53 seconds provide data bits which encode the current time, date, and related information.

The phase shift begins 0.1 s after the corresponding UTC second, so that the transition occurs while the carrier amplitude is low.

[15]: 2–4 The use of phase-shift keying allows a more sophisticated (but still very simple by modern electronics standards) receiver to distinguish 0 and 1 bits far more clearly, allowing improved reception on the East Coast of the United States where the WWVB signal level is weak, radio frequency noise is high, and the MSF time signal from the U.K. interferes at times.

This phase step was equivalent to "cutting and pasting" 1⁄8 of a 60 kHz carrier cycle, or approximately 2.08 μs.

The widest dark blue blocks — the longest intervals (0.8 s) of reduced carrier strength — are the markers, occurring in seconds 0, 9, 19, 29, 39, 49, and 59.

Of the remaining dark blue blocks, the narrowest represent reduced carrier strength of 0.2 seconds duration, hence data bits of value zero.

The DST status bits indicate United States daylight saving time rules.

[15] Like the amplitude-modulated code, the time is transmitted in the minute after the instant it identifies; clocks must increment it for display.

The phase-modulated code contains additional announcement bits useful for converting the broadcast UTC to civil time.

Also, since longwave signals tend to propagate much farther at night, the WWVB signal can reach a larger coverage area during that time period, which is why many radio-controlled clocks are designed to automatically synchronize with the WWVB time code during local nighttime hours.

The radiation pattern of WWVB antennas is designed to present a field strength of at least 100 μV/m over most of the continental United States and Southern Canada during some portion of the day.

Positioning receiving antennas away from electronic equipment helps to reduce the effects of local interference.