Milling (machining)

In a precise face milling operation, the revolution marks will only be microscopic scratches due to imperfections in the cutting edge.

For example, if several workpieces need a slot, a flat surface, and an angular groove, a good method to cut these (within a non-CNC context) would be gang milling.

Today, CNC mills with automatic tool change and 4- or 5-axis control obviate gang-milling practice to a large extent.

The spindle can generally be lowered (or the table can be raised, giving the same relative effect of bringing the cutter closer or deeper into the work), allowing plunge cuts and drilling.

A mill-drill is similar in basic configuration to a very heavy drill press, but equipped with an X-Y table and a much larger column.

They also typically use more powerful motors than a comparably sized drill press, most are muti-speed belt driven with some models having a geared head or electronic speed control.

A mill drill also typically raises and lowers the entire head, including motor, often on a dovetailed (sometimes round with rack and pinion) vertical column.

Other differences that separate a mill-drill from a drill press may be a fine tuning adjustment for the Z-axis, a more precise depth stop, the capability to lock the X, Y or Z axis, and often a system of tilting the head or the entire vertical column and powerhead assembly to allow angled cutting-drilling.

Because the cutters have good support from the arbor and have a larger cross-sectional area than an end mill, quite heavy cuts can be taken enabling rapid material removal rates.

This allows the table feed to be synchronized to a rotary fixture, enabling the milling of spiral features such as hypoid gears.

Work in which the spindle's axial movement is normal to one plane, with an endmill as the cutter, lends itself to a vertical mill, where the operator can stand before the machine and have easy access to the cutting action by looking down upon it.

When combined with the use of conical tools or a ball nose cutter, it also significantly improves milling precision without impacting speed, providing a cost-efficient alternative to most flat-surface hand-engraving work.

The older a machine, the greater the plurality of standards that may apply (e.g., Morse, Jarno, Brown & Sharpe, Van Norman, and other less common builder-specific tapers).

In pocket milling the material inside an arbitrarily closed boundary on a flat surface of a work piece is removed to a fixed depth.

For large-scale material removal, contour-parallel tool path is widely used because it can be consistently used with up-cut or down-cut method during the entire process.

[17] Milling machines evolved from the practice of rotary filing—that is, running a circular cutter with file-like teeth in the headstock of a lathe.

From a history-of-technology viewpoint, it is clear that the naming of this new type of machining with the term "milling" was an extension from that word's earlier senses of processing materials by abrading them in some way (cutting, grinding, crushing, etc.).

Milling wooden blanks results in a low yield of parts because the machines single blade would cause loss of gear teeth when the cutter hit parallel grains in the wood.

Other Connecticut clockmakers like James Harrison of Waterbury, Thomas Barnes of Litchfield, and Gideon Roberts of Bristol, also used milling machines to produce their clocks.

"[24] However, subsequent scholars, including Robert S. Woodbury[25] and others,[26] have improved upon Roe's early version of the history and suggest that just as much credit—in fact, probably more—belongs to various other inventors, including Robert Johnson of Middletown, Connecticut; Captain John H. Hall of the Harpers Ferry armory; Simeon North of the Staddle Hill factory in Middletown; Roswell Lee of the Springfield armory; and Thomas Blanchard.

Baida cites Battison's suggestion that the first true milling machine was made not by Whitney, but by Robert Johnson of Middletown.

[26] The late teens of the 19th century were a pivotal time in the history of machine tools, as the period of 1814 to 1818 is also the period during which several contemporary pioneers (Fox, Murray, and Roberts) were developing the planer,[27] and as with the milling machine, the work being done in various shops was undocumented for various reasons (partially because of proprietary secrecy, and also simply because no one was taking down records for posterity).

Some of the key men in milling machine development during this era included Frederick W. Howe, Francis A. Pratt, Elisha K. Root, and others.

It solved the problem of 3-axis travel (i.e., the axes that we now call XYZ) much more elegantly than had been done in the past, and it allowed for the milling of spirals using an indexing head fed in coordination with the table feed.

[31][32] Around the end of World War I, machine tool control advanced in various ways that laid the groundwork for later CNC technology.

It was small enough, light enough, and affordable enough to be a practical acquisition for even the smallest machine shop businesses, yet it was also smartly designed, versatile, well-built, and rigid.

Beginning in the 1930s, ideas involving servomechanisms had been in the air, but it was especially during and immediately after World War II that they began to germinate (see also Numerical control > History).

This technological development milieu, spanning from the immediate pre–World War II period into the 1950s, was powered by the military capital expenditures that pursued contemporary advancements in the directing of gun and rocket artillery and in missile guidance—other applications in which humans wished to control the kinematics/dynamics of large machines quickly, precisely, and automatically.

But during the 1960s and 1970s, NC evolved into CNC, data storage and input media evolved, computer processing power and memory capacity steadily increased, and NC and CNC machine tools gradually disseminated from an environment of huge corporations and mainly aerospace work to the level of medium-sized corporations and a wide variety of products.

Manufacturers have started producing economically priced CNCs machines small enough to sit on a desktop which can cut at high resolution materials softer than stainless steel.

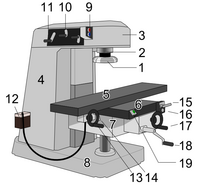

1: base

2: column

3: knee

4 & 5: table (x-axis slide is integral)

6: overarm

7: arbor (attached to spindle)