History of printing in East Asia

Printing in East Asia originated in China, evolving from ink rubbings made on paper or cloth from texts on stone tablets, used during the sixth century.

The semi-mythical record of him therefore describes his usage of the printing process to deliberately bewilder onlookers and create an image of mysticism around himself.

The Suishu jingjizhi, the blibography of the official history of the Sui dynasty, includes several ink-squeeze rubbings, believed to have led to the early duplication of texts that inspired printing.

This coincides with the reign of Wu Zetian, during which the Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra, which advocates the practice of printing apotropaic and merit-making texts and images, was translated by Chinese monks.

[15][16] The oldest extant evidence of woodblock prints created for the purpose of reading are portions of the Lotus Sutra discovered at Turpan in 1906.

This copy of the Diamond Sutra is 14 feet (4.3 metres) long and contains a colophon at the inner end, which reads: Reverently [caused to be] made for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong [i.e. 11 May, AD 868 ].

[3][16] The Diamond Sutra was closely followed by the earliest extant printed almanac, the Qianfu sinian lishu (乾符四年曆書), dated to 877.

The engraver uses a set of sharp-edged tools to cut away the uninked areas of the wood block in essence raising an inverse image of the original calligraphy above the background.

ukiyo-e is based on kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, beautiful women, landscapes of sightseeing spots, historical tales, and so on, and Hokusai and Hiroshige are the most famous artists.

A copy of the Buddhist Dharani Sutra called the Pure Light Dharani Sutra (Korean: 무구정광대다라니경; Hanja: 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經; RR: Mugu jeonggwang dae darani-gyeong), discovered in Gyeongju, South Korea in a Silla dynasty pagoda that was repaired in 751 CE,[26][27] was undated but must have been created sometime before the reconstruction of the Shakyamuni Pagoda (Korean: 석가탑; Hanja: 釋迦塔) of Bulguk Temple, Gyeongju Province in 751 CE.

In 1248 the complete Goryeo Daejanggyeong numbered 81,258 printing blocks of magnolia wood carved on both sides, 52,330,152 characters, 1496 titles, and 6568 volumes.

Around fifty pieces of Medieval Arabic blockprinting have been found in Egypt printed between 900 and 1300 in black ink on paper by the rubbing method in the Chinese style.

[39] Bi Sheng (990–1051) developed the first known movable-type system for printing in China around 1040 AD during the Northern Song dynasty, using ceramic materials.

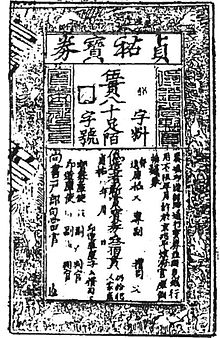

Another sample of Song dynasty money of the same period in the collection of Shanghai Museum has two empty square holes above Ziliao as well as Zihou, due to the loss of two copper movable types.

In 1725, the Qing dynasty government made 250,000 bronze movable-type characters and printed 64 sets of the encyclopedic Complete Classics Collection of Ancient China (《古今圖書集成》).

[40][54] In 1298, Wang Zhen (王禎), a Yuan dynasty governmental official of Jingde County, Anhui Province, China, re-invented a method of making movable wooden types.

This system was later enhanced by pressing wooden blocks into sand and casting metal types from the depression in copper, bronze, iron or tin.

[41] In 1322, a Fenghua county officer Ma Chengde (馬稱德) in Zhejiang, made 100,000 wooden movable types and printed 43 volume Daxue Yanyi (《大學衍義》).

Even as late as 1733, a 2300-volume Wuying Palace Collected Gems Edition (《武英殿聚珍版叢書》) was printed with 253,500 wooden movable type on order of the Yongzheng Emperor, and completed in one year.

[56] A particular difficulty posed the logistical problems of handling the several thousand logographs whose command is required for full literacy in the Chinese language.

A potential solution to the linguistic and cultural bottleneck that held back movable type in Korea for two hundred years appeared in the early 15th century—a generation before Gutenberg would begin working on his own movable type invention in Europe—when Koreans devised a simplified alphabet of 24 characters called Hangul, which required fewer characters to typecast.

[8] [63] The moveable type printing-press seized from Korea by Toyotomi Hideyoshi's forces in 1593 was also in use at the same time as the printing press from Europe.

[8][64] Tokugawa Ieyasu established a printing school at Enko-ji in Kyoto and started publishing books using domestic wooden movable type printing-press instead of metal from 1599.

[8] The great pioneers in applying movable type printing press to the creation of artistic books, and in preceding mass production for general consumption, were Honami Kōetsu and Suminokura Soan.

At their studio in Saga, Kyoto, the pair created a number of woodblock versions of the Japanese classics, both text and images, essentially converting emaki (handscrolls) to printed books, and reproducing them for wider consumption.

[65] For aesthetic reasons, the typeface of the Saga-bon, like that of traditional handwritten books, adopted the renmen-tai (ja), in which several characters are written in succession with smooth brush strokes.

[66][67][68] Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, craftsmen soon decided that the semi-cursive and cursive script style of Japanese writings was better reproduced using woodblocks.

[citation needed] It is unknown whether metal movable types used from the late 15th century in China were cast from moulds or carved individually.

Additionally, the ink traditionally used in Chinese printing, typically composed of pine soot bound with glue, didn't work well with the tin originally used for type.

[72] Instead, printing in East Asia remained an unmechanized, laborious process with pressing the back of the paper onto the inked block by manual "rubbing" with a hand tool.