NSA warrantless surveillance (2001–2007)

During the Obama administration, the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) continued to defend the warrantless surveillance program in court, arguing that a ruling on the merits would reveal state secrets.

The complete details of the executive order are not public, but according to administration statements,[4] the authorization covers communication originating overseas from or to a person suspected of having links to terrorist organizations or their affiliates even when the other party to the call is within the US.

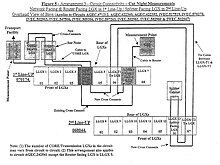

The precise scope of the program remains secret, but the NSA was provided total, unsupervised access to all fiber-optic communications between the nation's largest telecommunication companies' major interconnected locations, encompassing phone conversations, email, Internet activity, text messages and corporate private network traffic.

[19] CRS released a report on the NSA program, "Presidential Authority to Conduct Warrantless Electronic Surveillance to Gather Foreign Intelligence Information", on January 5, 2006 that concluded: While courts have generally accepted that the President has the power to conduct domestic electronic surveillance within the United States inside the constraints of the Fourth Amendment, no court has held squarely that the Constitution disables the Congress from endeavoring to set limits on that power.

In Hamdi v. Rumsfeld (2004) the government claimed that AUMF authorized the detention of U.S. citizens designated as an enemy combatant despite its lack of specific language to that effect and notwithstanding the provisions of 18 U.S.C.

In that case, the Court ruled: [B]ecause we conclude that the Government's second assertion ["that § 4001(a) is satisfied, because Hamdi is being detained "pursuant to an Act of Congress" [the AUMF]"] is correct, we do not address the first.

[35] According to a lawsuit filed against other telecommunications companies for violating customer privacy, AT&T began preparing facilities for the NSA to monitor "phone call information and Internet traffic" seven months before 9/11.

[43][29][44] Judicial Watch, a watchdog group, discovered that at the time of the ruling Taylor "serves as a secretary and trustee for a foundation that donated funds to the ACLU of Michigan, a plaintiff in the case".

On August 17, 2007, FISC said it would consider a request by the ACLU that asked the court to make public its recent, classified rulings on the scope of the government's wiretapping powers.

The Supreme Court has used the "necessary and proper" clause to affirm broad Congressional authority to legislate as it sees fit in the domestic arena,[83] but has limited its application in foreign affairs.

Such circumstances include the persons, property and papers of individuals crossing the border of the United States and those of paroled felons; prison inmates, public schools and government offices; and of international mail.

They noted that all of the Federal courts of appeal had considered the issue and concluded that constitutional power allowed the president to conduct warrantless foreign intelligence surveillance.

The legality of surveillance involving US persons and extent of this authorization is the core of this controversy which includes: Because of its highly classified status, the implementation of the TSP is not fairly known by the public.

[108][109] Klein's January 16, 2004 statement included additional details regarding the construction of an NSA monitoring facility in Room 641A of 611 Folsom Street in San Francisco, the site of a large SBC phone building, three floors of which were occupied by AT&T.

[113] They concluded that the likely architecture of the system created serious security risks, including the danger that it could be exploited by unauthorized users, criminally misused by trusted insiders or abused by government agents.

Supporters claimed that the President's Constitutional duties as commander in chief allowed him to take all necessary steps in wartime to protect the nation and that AUMF activated those powers.

In such a separation of powers dispute, Congress bears burden of proof to establish its supremacy: the Executive branch enjoys the presumption of authority until an Appellate Court rules against it.

[120] Whether "proper exercise" of Congressional war powers includes authority to regulate the gathering of foreign intelligence is a historical point of contention between the Executive and Legislative branches.

Presidents have long contended that the ability to conduct surveillance for intelligence purposes is a purely executive function, and have tended to make broad assertions of authority while resisting efforts on the part of Congress or the courts to impose restrictions.

Assistant Attorney General for Legislative Affairs, William Moschella, wrote: As explained above, the President determined that it was necessary following September 11 to create an early warning detection system.

In addition, any legislative change, other than the AUMF, that the President might have sought specifically to create such an early warning system would have been public and would have tipped off our enemies concerning our intelligence limitations and capabilities.FBI Special Agent Coleen Rowley, in her capacity as legal counsel to the Minneapolis Field Office[130] recounted how FISA procedural hurdles had hampered the FBI's investigation of Zacarias Moussaoui (the so-called "20th hijacker") prior to the 9/11 attacks.

[135] However, Chief Judge Walker stated, during the September 12, 2008 hearing in the EFF class-action lawsuit, that the Klein evidence could be presented in court, effectively ruling that AT&T's trade secret and security claims were unfounded.

"[138] Cole, Epstein, Heynmann, Beth Nolan, Curtis Bradley, Geoffrey Stone, Harold Koh, Kathleen Sullivan, Laurence Tribe, Martin Lederman, Ronald Dworkin, Walter Dellinger, William Sessions and William Van Alstyne wrote, "the Justice Department's defense of what it concedes was secret and warrantless electronic surveillance of persons within the United States fails to identify any plausible legal authority for such surveillance.

This is domestic surveillance over American citizens for whom there is no evidence or proof that they are involved in any illegal activity, and it is in contravention of a statute of Congress specifically designed to prevent this.Law professor Robert M. Bloom and William J. Dunn, a former Defense Department intelligence analyst, claimed:[142] President Bush argues that the surveillance program passes constitutional inquiry based upon his constitutionally delegated war and foreign policy powers, as well as from the congressional joint resolution passed following the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks.

The specific regulation by Congress based upon war powers shared concurrently with the President provides a constitutional requirement that cannot be bypassed or ignored by the President.Law professor Jordan Paust argued:[143] any so-called inherent presidential authority to spy on Americans at home (perhaps of the kind denounced in Youngstown (1952) and which no strict constructionist should pretend to recognize), has been clearly limited in the FISA in 18 U.S.C.

[4] Critics pointed out that the first warrantless surveillance occurred before the adoption of the U.S. Constitution, and the other historical precedents cited by the administration were before FISA's passage and therefore did not directly contravene federal law.

Hayden implied that decisions on whom to intercept under the wiretapping program were being made on the spot by a shift supervisor and another person, but refused to discuss details of the specific requirements for speed.

[171] DOJ sent a 42-page white paper to Congress on January 19, 2006 stating the grounds upon which it was felt the NSA program was legal, which restated and elaborated on reasoning Gonzales used at the December press conference.

[39] In introducing their resolution to committee,[178] they quoted Supreme Court Justice Sandra Day O'Connor's opinion that even war "is not a blank check for the President when it comes to the rights of the Nation's citizens".

Leahy and Kennedy also asserted that Gonzales had "admitted" at a press conference on December 19, 2005, that the Administration did not seek to amend FISA to authorize the NSA spying program because it was advised that "it was not something we could likely get."