Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War

[1] The shock of the Union defeat at the First Battle of Bull Run in July 1861, with demoralized troops wandering the streets of the capital, caused President Abraham Lincoln to order extensive fortifications and a large garrison.

[1] When Lincoln was assassinated in Ford's Theater in April 1865,[2] thousands flocked into Washington to view the coffin, further raising the profile of the city.

The new president, Andrew Johnson, wanted to dispel the funereal atmosphere and organized a program of victory parades, which revived public hopes for the future.

In February 1861, the Peace Congress, a last-ditch attempt by delegates from 21 of the 34 states to avert what many saw as the impending civil war, met in the city's Willard Hotel.

When Brigadier General Irvin McDowell's beaten and demoralized army staggered back into Washington after the stunning Confederate victory at the First Battle of Bull Run.

Upon hearing a Union regiment singing "John Brown's Body" as the soldiers marched beneath her window, the resident Julia Ward Howe wrote the patriotic "Battle Hymn of the Republic" to the same tune.

Warehouses, supply depots, ammunition dumps, and factories were established to provide and distribute material for the Union armies, and civilian workers and contractors flocked to the city.

[9] Washington became a popular place for formerly enslaved people to congregate, and many were employed in constructing the ring of fortresses that eventually surrounded the city.

One notable exception was during the Battle of Fort Stevens on July 11–12, 1864 in which Union soldiers repelled troops under the command of Confederate Lieutenant General Jubal A.

[10] Hospitals in the Washington area became significant providers of medical services to wounded soldiers needing long-term care after they had been transported to the city from the front lines over the Long Bridge or by steamboat at the Wharf.

The Army Corps of Engineers constructed a new aqueduct that brought 10,000 US gallons (38,000 L; 8,300 imp gal) of fresh water to the city each day.

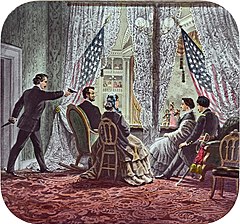

[19] On April 14, 1865, just days after the end of the war, Lincoln was shot in Ford's Theater by John Wilkes Booth during the play Our American Cousin.

Scores of residents and workers were questioned during the growing investigation, and some were detained or arrested on suspicion of having aided the assassins or for a perception that they were withholding information.

[25] Lincoln's body was displayed in the Capitol rotunda,[26] and thousands of Washington residents and as throngs of visitors stood in long queues for hours to glimpse the fallen president.

Following the identification and eventual arrest of the actual conspirators, the city was the site of the trial and execution of several of the assassins, and Washington was again the center of the nation's media attention.

On May 9, 1865, the new president, Andrew Johnson, declared that the rebellion had virtually ended, and he planned with government authorities a formal review to honor the victorious troops.

The mood in Washington was now one of gaiety and celebration, and the crowds and soldiers frequently engaged in singing patriotic songs as column passed the reviewing stand in front of the White House, where Johnson, General-in-Chief Ulysses S. Grant, senior military leaders, the Cabinet, and leading government officials awaited.

Other important personalities of the Civil War born in the immediate Washington area included Confederate Senator Thomas Jenkins Semmes, Union general John Milton Brannan, John Rodgers Meigs (whose death sparked a significant controversy throughout the North), and Confederate brigade commander Richard Hanson Weightman.