Water scarcity

[5] This can happen due to an increase in the number of people in a region, changing living conditions and diets, and expansion of irrigated agriculture.

Such symptoms could be "growing conflict between users, and competition for water, declining standards of reliability and service, harvest failures and food insecurity".

A previous definition in Millennium Development Goal 7, target 7.A, was simply the proportion of total water resources used, without taking EFR into consideration.

[32] In 2019 the World Economic Forum listed water scarcity as one of the largest global risks in terms of potential impact over the next decade.

Other examples are economic competition for water quantity or quality, disputes between users, irreversible depletion of groundwater, and negative impacts on the environment.

[41] By 2025, 1.8 billion people will be living in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity, and two-thirds of the world population could be under stress conditions.

[42] By 2050, more than half of the world's population will live in water-stressed areas, and another billion may lack sufficient water, MIT researchers find.

The drying out of wetlands globally, at around 67%, was a direct cause of a large number of people at risk of water stress.

It also said: "Water insufficiency is often due to mismanagement, corruption, lack of appropriate institutions, bureaucratic inertia and a shortage of investment in both human capacity and physical infrastructure".

The U.S. Geological Survey estimates that subsidence has affected more than 17,000 square miles in 45 U.S. states, 80 percent of it due to groundwater usage.

In the case of wetlands, a lot of ground has been simply taken from wildlife use to feed and house the expanding human population.

People were not as wealthy as today, consumed fewer calories and ate less meat, so less water was needed to produce their food.

[65] In building on the data presented here by the UN, the World Bank[66] goes on to explain that access to water for producing food will be one of the main challenges in the decades to come.

They expanded the irrigation sector which made it possible to increase food production and development in rural areas.

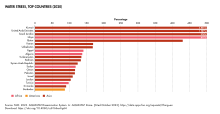

They are India, China, United States of America, Pakistan, Iran, Bangladesh, Mexico, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, and Italy.

To avoid a global water crisis, farmers will have to increase productivity to meet growing demands for food.

There is now ample evidence that greater hydrologic variability and climate change have had a profound impact on the water sector, and will continue to do so.

[87] The United Nations' FAO states that by 2025 1.9 billion people will live in countries or regions with absolute water scarcity.

A reduction in runoff will affect the ability to irrigate crops and will reduce summer stream flows necessary to keep dams and reservoirs replenished.

This situation is particularly acute for irrigation in South America, where numerous artificial lakes are filled almost exclusively by glacial melt.

[90] Central Asian countries have also been historically dependent on the seasonal glacier melt water for irrigation and drinking supplies.

These would take into account the entire water cycle: from source to distribution, economic use, treatment, recycling, reuse and return to the environment.

However, the use of virtual water estimates may offer no guidance for policymakers seeking to ensure they are meeting environmental objectives.

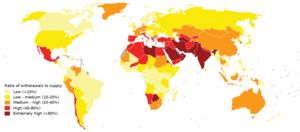

The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) published a map showing the countries and regions suffering most water stress.

[citation needed] Most of South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, southern China and India will face water supply shortages by 2025.

For these regions, scarcity will be due to economic constraints on developing safe drinking water, and excessive population growth.

In Nigeria, some reports have suggested that increase in extreme heat, drought and the shrinking of Lake Chad is causing water shortage and environmental migration.

[130] These glaciers are the sources of Asia's biggest rivers – Ganges, Indus, Brahmaputra, Yangtze, Mekong, Salween and Yellow.

Unless population growth can be slowed quickly, it is feared that there may not be a practical non-violent or humane solution to the emerging world water shortage.

Scholars such as Mexico's Armand Peschard-Sverdrup have argued that this tension has created the need for new strategic transnational water management.