Water table

In areas with sufficient precipitation, water infiltrates through pore spaces in the soil, passing through the unsaturated zone.

At increasing depths, water fills in more of the pore spaces in the soils, until a zone of saturation is reached.

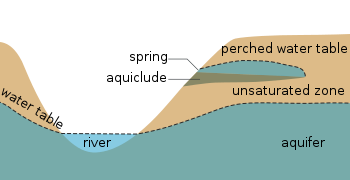

Below the water table, in the zone of saturation, layers of permeable rock that yield groundwater are called aquifers.

In less permeable soils, such as tight bedrock formations and historic lakebed deposits, the water table may be more difficult to define.

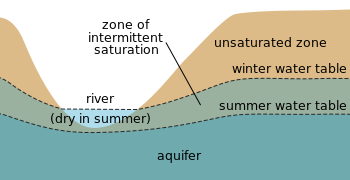

In undeveloped regions with permeable soils that receive sufficient amounts of precipitation, the water table typically slopes toward rivers that act to drain the groundwater away and release the pressure in the aquifer.

The water table does not always mimic the topography due to variations in the underlying geological structure (e.g., folded, faulted, fractured bedrock).

It is non-renewable by present-day rainfall due to its depth below the surface, and any extraction causes a permanent change in the water table in such regions.

This is conspicuous in Berlin, which is built on sandy, marshy ground, and the water table is generally 2 meters below the surface.