Interpersonal ties

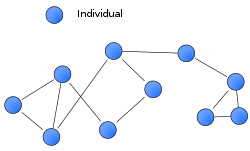

In social network analysis and mathematical sociology, interpersonal ties are defined as information-carrying connections between people.

[4] One of the earliest writers to describe the nature of the ties between people was German scientist and philosopher, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe.

The analogy shows how strong marriage unions are similar in character to particles of quicksilver, which find unity through the process of chemical affinity.

In 1973, stimulated by the work of Rapoport and Harvard theorist Harrison White, Mark Granovetter published The Strength of Weak Ties.

[6] To obtain data for his doctoral thesis, Granovetter interviewed dozens of people to find out how social networks are used to land new jobs.

[9] In 1970, Granovetter submitted his doctoral dissertation to Harvard University, entitled "Changing Jobs: Channels of Mobility Information in a Suburban Community".

For his research, Dr. Granovetter crossed the Charles River to Newton, Massachusetts where he surveyed 282 professional, technical, and managerial workers in total.

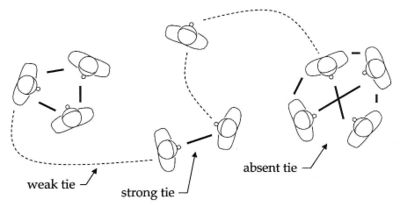

[12] It may follow that individuals with few bridging weak ties will be deprived of information from distant parts of the social system and will be confined to the provincial news and views of their close friends.

The first one refers to the fact that the Granovetter definition of the strength of a tie is a curvilinear prediction and his question is "how do we know where we are on this theoretical curve?".

Strong ties constitute a base of trust that can reduce resistance and provide comfort in the face of uncertainty.

"He called this particular type of strong tie philo and define philos relationship as one that meets the following three necessary and sufficient conditions: The combination of these qualities predicts trust and predicts that strong ties will be the critical ones in generating trust and discouraging malfeasance.

Starting in the late 1940s, Anatol Rapoport and others developed a probabilistic approach to the characterization of large social networks in which the nodes are persons and the links are acquaintanceship.

This effort led to an important and non-obvious Structure Theorem for signed graphs,[14] which was published by Frank Harary in 1953.

For instance, in 1952 Herbert A. Simon produced a mathematical formalization of a published theory of social groups by constructing a model consisting of a deterministic system of differential equations.

[3] Adding any network-based means of communication such as a new IRC channel, a social support group, a Webboard lays the groundwork for connectivity between formerly unconnected others.

They are only activated, i.e. converted from latent to weak, by some sort of social interaction between members, e.g. by telephoning someone, attending a group-wide meeting, reading and contributing to a Webboard, emailing others, etc.

These are started by individuals with a particular interest in a subject who may begin by posting information and providing the means for online discussion.

[16] Granovetter's 1973 work proved to be crucial in the individualistic approach of the social network theory as seen by the number of references in other papers.

Sparrowe & Linden (1997) argue how the position of a person in a social network confer advantages such organizational assimilation, and job performance (Sparrowe et al., 2001); Burt (1992) expects it to result in promotions, Brass (1984) affiliates centrality with power and Friedkin (1993) with influence in decision power.

Blau and Fingerman, drawing from these and other studies, refer to weak ties as consequential strangers, positing that they provide some of the same benefits as intimates as well as many distinct and complementary functions.

[18] In the early 1990s, US social economist James D. Montgomery contributed to economic theories of network structures in the labour market.

[19] In 1992, Montgomery explored the role of "weak ties", which he defined as non-frequent and transitory social relations in the labour market.