Weber problem

It was formulated by the famous French mathematician Pierre de Fermat before 1640, and it can be seen as the true beginning of both location theory, and space-economy.

E. Weiszfeld published a paper in 1937 with an algorithm for the Fermat-Weber problem.

As the paper was published in Tohoku Mathematical journal, and Weiszfeld immigrated to USA and changed his name to Vaszoni, his work was not widely known.

[1] Kuhn and Kuenne[2] independently found a similar iterative solution for the general Fermat problem in 1962, and, in 1972, Tellier[3] found a direct numerical solution to the Fermat triangle problem, which is trigonometric.

It was first formulated, and solved geometrically in the triangle case, by Thomas Simpson in 1750.

Kuhn and Kuenne's solution applies also to the case of polygons having more than three sides.

It was first formulated and solved, in the triangle case, in 1985 by Luc-Normand Tellier.

[6] In 1992, Chen, Hansen, Jaumard and Tuy found a solution to the Tellier problem for the case of polygons having more than three sides.

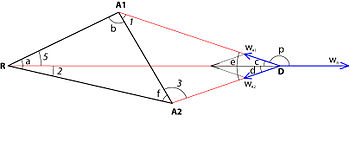

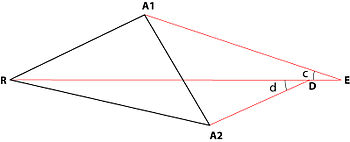

Evangelista Torricelli’s geometrical solution of the Fermat triangle problem stems from two observations: It can be proved that the first observation implies that, at the optimum, the angles between the AD, BD, CD straight lines must be equal to 360° / 3 = 120°.

Torricelli deduced from that conclusion that: Simpson's geometrical solution of the so-called "Weber triangle problem" (which was first formulated by Thomas Simpson in 1750) directly derives from Torricelli's solution.

Simpson and Weber stressed the fact that, in a total transportation minimization problem, the advantage to get closer to each attraction point A, B or C depends on what is carried and on its transportation cost.

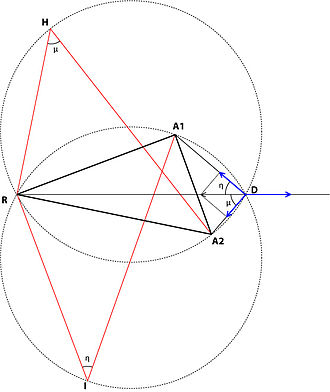

That third circumference crosses the two previous ones at the same point D. A geometrical solution exists for the attraction-repulsion triangle problem.

[7] That geometrical solution differs from the two previous ones since, in this case, the two constructed force triangles overlap the △A1A2R location triangle (where A1 and A2 are attraction points, and R, a repulsion one), while, in the preceding cases, they never did.

More than 332 years separate the first formulation of the Fermat triangle problem and the discovery of its non-iterative numerical solution, while a geometrical solution existed for almost all that period of time.

That explanation lies in the possibility of the origins of the three vectors oriented towards the three attraction points not coinciding.

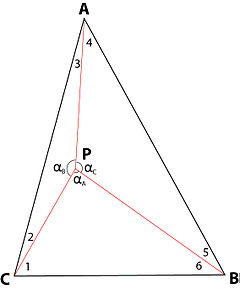

If those origins do coincide and lie at the optimum location P, the vectors oriented towards A, B, C, and the sides of the △ABC location triangle form the six angles ∠1, ∠2, ∠3, ∠4, ∠5, ∠6, and the three vectors form the ∠αA, ∠αB, ∠αC angles.

Unfortunately, this system of six simultaneous equations with six unknowns is undetermined, and the possibility of the origins of the three vectors oriented towards the three attraction points not coinciding explains why.

However, the optimal location P has disappeared because of the triangular hole that exists inside the triangle.

In fact, as Tellier (1972)[8] has shown, that triangular hole had exactly the same proportions as the "forces triangles" we drew in Simpson's geometrical solution.

In order to solve the problem, we must add to the six simultaneous equations a seventh requirement, which states that there should be no triangular hole in the middle of the location triangle.

Here as in the previous case, the possibility exists for the origins of the three vectors not to coincide.

Tellier's trigonometric solution of this problem is the following: When the number of forces is larger than three, it is no longer possible to determine the angles separating the various forces without taking into account the geometry of the location polygon.

In this method, to find an approximation to the point y minimizing the weighted sum of distances

an initial approximation to the solution y0 is found, and then at each stage of the algorithm is moved closer to the optimal solution by setting yj + 1 to be the point minimizing the sum of weighted squared distances

The Varignon frame provides an experimental solution of the Weber problem.

For the attraction–repulsion problem one has instead to resort to the algorithm proposed by Chen, Hansen, Jaumard and Tuy (1992).

[11] In the world of spatial economics, repulsive forces are omnipresent.

In fact a substantial portion of land value theory, both rural and urban, can be summed up in the following way.

The Tellier problem preceded the emergence of the New Economic Geography.

It is seen by Ottaviano and Thisse (2005)[12] as a prelude to the New Economic Geography (NEG) that developed in the 1990s, and earned Paul Krugman a Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences in 2008.