History of Wales

In the post-Roman period, a number of Welsh kingdoms formed in present-day Wales, including Gwynedd, Powys, Ceredigion, Dyfed, Brycheiniog, Ergyng, Morgannwg, and Gwent.

The 18th century saw the beginnings of two changes that would greatly affect Wales: the Welsh Methodist revival, which led the country to turn increasingly nonconformist in religion, and the Industrial Revolution.

[6][7][8] Following the last ice age, Wales became roughly the shape it is today by about 8000 BC and was inhabited by small numbers (a few hundred) of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.

The most notable examples of megalithic tombs include Bryn Celli Ddu and Barclodiad y Gawres on Anglesey,[11] Pentre Ifan in Pembrokeshire, and Tinkinswood Burial Chamber in the Vale of Glamorgan.

[13][14] The historian John Davies theorised that the story of Cantre'r Gwaelod's drowning and tales in the Mabinogion, of the waters between Wales and Ireland being narrower and shallower, may be distant folk memories of this time.

[28] A second wave (c. 500 BC- 200 BC) of migration of Celtic tribes from Eastern Europe emerged in Britain and established stone hut circle roundhouse settlements within or near the previously inhabited hillfort enclosures.

It is these campaigns of conquest that are the most widely known feature of Wales during the Roman era due to the spirited but unsuccessful defence of their homelands by two native tribes, the Silures and the Ordovices.

The Demetae of southwestern Wales seem to have quickly made their peace with the Romans, as there is no indication of war with Rome, and their homeland was not heavily planted with forts nor overlaid with roads.

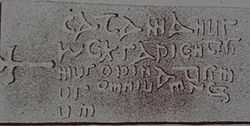

[36] He is given as the ancestor of a Welsh king on the Pillar of Eliseg in the 9th century,[43] erected nearly 500 years after he left Britain, and he appears in lists of the Fifteen Tribes of Wales.

[49] It has been suggested that this battle finally severed the land connection between Wales and the kingdoms of the Hen Ogledd ("Old North"), the Brittonic-speaking regions of what is now southern Scotland and northern England, including Rheged, Strathclyde, Elmet and Gododdin, where Old Welsh was also spoken.

According to Davies, this had been with the agreement of king Elisedd ap Gwylog of Powys, as this boundary, extending north from the valley of the River Severn to the Dee estuary, gave him Oswestry.

On the Long Mountain near Trelystan, the dyke veers to the east, leaving the fertile slopes in the hands of the Welsh; near Rhiwabon, it was designed to ensure that Cadell ap Brochwel retained possession of the Fortress of Penygadden."

Rhodri's grandson Hywel Dda (r. 900–50) founded Deheubarth out of his maternal and paternal inheritances of Dyfed and Seisyllwg in 930, ousted the Aberffraw dynasty from Gwynedd and Powys and then codified Welsh law in the 940s.

The Kingdom of Gwynedd was established in North West Wales during the year 401 by Cunedda Wledig, a Roman soldier who hailed from Manaw Gododdin (Scotland) to pacify the invading fellow Celts from Ireland.

This kingdom originally extended east into areas now in England, and its ancient capital, Pengwern, has been variously identified as modern Shrewsbury or a site north of Baschurch.

According to the chronicle Brut y Tywysogion, Godfrey Haroldson carried off two thousand captives from Anglesey in 987, and the king of Gwynedd, Maredudd ab Owain is reported to have redeemed many of his subjects from slavery by paying the Danes a large ransom.

His son, Owain Gwynedd, allied with Gruffydd ap Rhys of Deheubarth won a crushing victory over the Normans at the Battle of Crug Mawr in 1136 and annexed Ceredigion.

Friendship broke down and John invaded parts of Gwynedd in 1211, taking Llywelyn's eldest son as hostage, and also forcing the surrender of territory in north-east Wales.

[99] His son Dafydd ap Llywelyn followed him as ruler of Gwynedd, but King Henry III of England would not allow him to inherit his father's position elsewhere in Wales.

[105] A series of subsequent disputes, including the imprisonment of Llywelyn's wife Eleanor, culminated in a declaration of war and the first invasion by King Edward I of England in November 1276.

After passing the Statute of Rhuddlan, which restricted Welsh law,[114] Edward constructed a series of castles to maintain his dominance: Beaumaris, Caernarfon, Harlech and Conwy.

Wales was overwhelmingly Royalist in the Wars of the Three Kingdoms in the early 17th century, though there were some notable exceptions such as John Jones Maesygarnedd and the Puritan writer Morgan Llwyd.

[158] Kenneth O. Morgan argues that the 1850-1914 era: was a story of growing political democracy with the hegemony of the Liberals in national and local government, of an increasingly thriving economy in the valleys of South Wales, the world's dominant coal-exporting area with massive ports at Cardiff and Barry, increasingly buoyant literature and a revival in the eisteddfod, and of much vitality in the nonconformist chapels especially after the short-lived impetus from the ‘great revival’, Y Diwygiad Mawr, of 1904–5.

Since 1865, the Liberal Party had held a parliamentary majority in Wales and, following the general election of 1906, only one non-Liberal Member of Parliament, Keir Hardie of Merthyr Tydfil, represented a Welsh constituency at Westminster.

[162] In December 1918, Lloyd George was re-elected as the head of a Conservative-dominated coalition government, and his poor handling of the 1919 coal miners' strike was a key factor in destroying support for the Liberal party in south Wales.

[166] After economic growth in the first two decades of the 20th century, Wales's staple industries endured a prolonged slump from the early 1920s to the late 1930s, leading to widespread unemployment and poverty.

[169] In the immediate period after the Second World War there was a strong revival in economic growth, accompanied by greater personal material well-being for the poorer elements of society as a result of the new systems of social welfare.

[177] This policy, begun in 1934, was enhanced by the construction of industrial estates and improvements in transport communications,[177] most notably the M4 motorway linking south Wales directly to London.

It was believed that the foundations for stable economic growth had been firmly established in Wales during this period, but this was shown to be optimistic after the recession of the early 1980s saw the collapse of much of the manufacturing base that had been built over the preceding forty years.

[194] Various public and private sector bodies have adopted bilingualism to a varying degree and (since 2011) Welsh is the only official (de jure) language in any part of Great Britain.