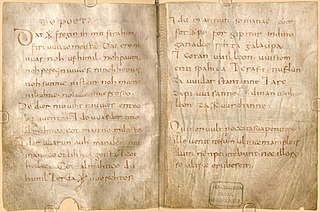

Wessobrunn Prayer

The poem is named after Wessobrunn Abbey, a Benedictine monastery in Bavaria, where the sole manuscript containing the text was formerly kept.

[5] The language has some Bavarian characteristics (cootlîh, paum, pereg) besides traces of Low German or Anglo-Saxon influence, specifically in the first line (dat is Low German; gafregin ih parallels OS gifragn ik and AS ȝefraeȝn ic).

[6] Anglo-Saxon influence is further suggested by the scribe's representation of the word enti "and" (with one exception) by Tironian et (⁊), and by the use of a "star-rune" 🞵 (a bindrune combining g and i) to represent the syllable ga-[7] shared by only one other manuscript, also Bavarian, viz., Arundel MS 393 in the British Library.

[9] The text was printed, without attempts at an interpretation, by Bernhard Pez in 1721,[10] again in Monumenta Boica in 1767, under the title De Poeta * Kazungali,[11] and again by Johann Wilhelm Petersen, Veränderungen und Epochen der deutschen Hauptsprache (1787).

[13] The word Kazungali printed in the 1767 transcription was interpreted as the name of the poem's author, but this was recognized as mistaken by Docen (1809).

63r), where [ars] poetica is glossed with "x kazungali" (with an "asterisk" symbol reminiscent of the "star-rune" but with horizontal bar).

Some features in the first section reflect the language and idiom of Germanic epic poetry, using alliteration and poetic formulae known from the Norse, Anglo-Saxon and Old Saxon traditions (ero ... noh ufhimil, manno miltisto, dat gafregin ih).

The cosmological passages in the poem have frequently been compared to similar material in the Voluspa, and in the Rigvedic Nasadiya Sukta.

Against this, Wackernagel (1827:17ff) holds that the emphasis of a creatio ex nihilo is genuinely Christian and not found in ancient cosmogonies.

⁊ du mannun ſomanac coot forᛡpi· for gipmir indina ganada rehta galaupa: ⁊ cotan uuilleon· uuiſtóm· enti ſpahida.

Dô dar niuuiht ni uuas enteô ni uuenteô, enti dô uuas der eino almahtîco cot, manno miltisto, enti (dar uuârun auh)[23] manakê mit inan[24] cootlîhhê geistâ.

One of the most unusual settings is by the German composer Helmut Lachenmann in his Consolation II (1968), in which component phonetic parts of the words of the prayer are vocalised separately by the 16 solo voices in a texture of vocal 'musique concrète'.

More recent interpretations by composers in the classical tradition include those by Felix Werder in 1975 for voice and small orchestra, and by Michael Radulescu in two works: De Poëta in 1988 for four choirs and bells, and in another arrangement of 1991 re-worked in 1998 for soprano and organ.

Canadian-born composer Joy Decoursey-Porter features the text in her piece for SSAATTBB a capella voices, There Was the One.

Medieval folk groups have adapted the text, including Estampie in their album Fin Amor (2002), and In Extremo in Mein rasend Herz (2005).