Western hunter-gatherer

WHGs share a closer genetic relationship to ancient and modern peoples in the Middle East and the Caucasus than earlier European hunter-gatherers.

[3] These Magdalenian peoples largely descended from earlier Western European Cro-Magnon groups that had arrived in the region over 30,000 years ago, prior to the Last Glacial Maximum.

This date was subsequently put further back in time by the findings of the Yana Rhinoceros Horn Site to around 38kya, shortly after the divergence of West-Eurasian and East-Eurasian lineages.

[7][11] Vallini et al. 2022 argues that the dispersal and split patterns of West Eurasian lineages was not earlier than c. 38,000 years ago, with older Initial Upper Paleolithic European specimens, such as those found in the Zlaty Kun, Peștera cu Oase and Bacho Kiro caves, being unrelated to Western hunter-gatherers but closer to Ancient East Eurasians or basal to both.

[3] A 2022 study proposed that the WHG/Villabruna population genetically diverged from hunter-gatherers in the Middle East and the Caucasus around 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum.

[13] WHG genomes display higher affinity for ancient and modern Middle Eastern populations when compared against earlier Paleolithic Europeans such as Gravettians.

The affinity for ancient Middle Eastern populations in Europe increased after the Last Glacial Maximum, correlating with the expansion of WHG (Villabruna or Oberkassel) ancestry.

The paternal haplogroup C-V20 can still be found in men living in modern Spain, attesting to this lineage's longstanding presence in Western Europe.

The Villabruna cluster also carried the Y-haplogroup R1b (R1b-L754), derived from the Ancient North Eurasian haplogroup R*, indicating "an early link between Europe and the western edge of the Steppe Belt of Eurasia.

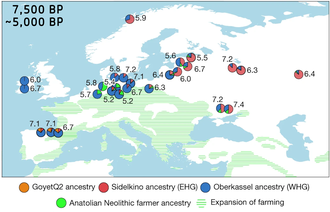

[3][17] A 2023 study found that relative to earlier Western European Cro-Magnon populations like the Gravettians, that Magdalenian-associated Goyet-Q2 cluster carried significant (~30%) Villabruna ancestry even prior to the major expansion of WHG-related groups north of the Alps.

[3] The study suggests that Oberkassel ancestry was mostly already formed before expanding, possibly around the west side of the Alps, to Western and Central Europe and Britain, where sampled WHG individuals are genetically homogeneous.

This, and the survival of specific Y-DNA haplogroup C1 clades previously observed among early European hunter-gatherers, suggests relatively higher genetic continuity in southwest Europe during this period.

[3] The WHG were also found to have contributed ancestry to populations on the borders of Europe such as early Anatolian farmers and Ancient Northwestern Africans,[19] as well as other European groups such as eastern hunter-gatherers.

[20] EHGs are modeled to derive varying degrees of ancestry from a WHG-related lineage, ranging from merely 25% to up to 91%, with the remainder being linked to geneflow from Paleolithic Siberians (ANE) and perhaps Caucasus hunter-gatherers.

Samples from the Ukrainian Mesolithic and Neolithic were found to cluster tightly together between WHG and EHG, suggesting genetic continuity in the Dnieper Rapids for a period of 4,000 years.

The analysis suggested that WHGs were once widely distributed from the Atlantic coast in the West, to Sicily in the South, to the Balkans in the Southeast, for more than six thousand years.

The Early European Farmer (EEF) component was identified based on the genome of a woman buried c. 7,000 years ago in a Linear Pottery culture grave in Stuttgart, Germany.

[34][35] Around 6000 BC, the WHGs of Italy were almost completely genetically replaced by EEFs (two G2a2) and one Haplogroup R1b, although WHG ancestry slightly increased in subsequent millennia.

[49] Some authors have expressed caution regarding skin pigmentation reconstructions: Quillen et al. (2019) acknowledge studies that generally show that "lighter skin color was uncommon across much of Europe during the Mesolithic", including studies regarding the “dark or dark to black” predictions for the Cheddar Man, but warn that "reconstructions of Mesolithic and Neolithic pigmentation phenotype using loci common in modern populations should be interpreted with some caution, as it is possible that other as yet unexamined loci may have also influenced phenotype.

"[50] Geneticist Susan Walsh at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, who worked on Cheddar Man project, said that "we simply don't know his skin colour".

[52] A 2024 research into the genomic ancestry and social dynamics of the last hunter-gatherers of Atlantic France has stated that "phenotypically, we find some diversity during the Late Mesolithic in France", at which two of the WHG's sequenced in the study "likely had pale to intermediate skin pigmentation", but "most individuals carry the dark skin and blue eyes characteristic of WHGs" of the studied samples.