Vector bundle

could be a topological space, a manifold, or an algebraic variety): to every point

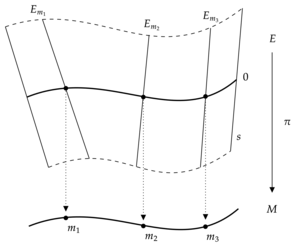

(e.g. a topological space, manifold, or algebraic variety), which is then called a vector bundle over

For example, the tangent bundle of the sphere is non-trivial by the hairy ball theorem.

In general, a manifold is said to be parallelizable if, and only if, its tangent bundle is trivial.

In the following, we focus on real vector bundles in the category of topological spaces.

A real vector bundle consists of: where the following compatibility condition is satisfied: for every point

Often the definition of a vector bundle includes that the rank is well defined, so that

over which the bundle trivializes via the composite function is well-defined on the overlap, and satisfies for some

The set of transition functions forms a Čech cocycle in the sense that for all

We can also consider the category of all vector bundles over a fixed base space X.

With the pointwise addition and scalar multiplication of sections, F(U) becomes itself a real vector space.

If s is an element of F(U) and α: U → R is a continuous map, then αs (pointwise scalar multiplication) is in F(U).

Not every sheaf of OX-modules arises in this fashion from a vector bundle: only the locally free ones do.

(The reason: locally we are looking for sections of a projection U × Rk → U; these are precisely the continuous functions U → Rk, and such a function is a k-tuple of continuous functions U → R.) Even more: the category of real vector bundles on X is equivalent to the category of locally free and finitely generated sheaves of OX-modules.

A rank n vector bundle is trivial if and only if it has n linearly independent global sections.

Each of these operations is a particular example of a general feature of bundles: that many operations that can be performed on the category of vector spaces can also be performed on the category of vector bundles in a functorial manner.

This fails if X is not compact: for example, the tautological line bundle over the infinite real projective space does not have this property.

Usually this metric is required to be positive definite, in which case each fibre of E becomes a Euclidean space.

More generally, one can typically understand the additional structure imposed on a vector bundle in terms of the resulting reduction of the structure group of a bundle.

[2] Specifically, one must require that the local trivializations are Banach space isomorphisms (rather than just linear isomorphisms) on each of the fibers and that, furthermore, the transitions are continuous mappings of Banach manifolds.

Depending on the required degree of smoothness, there are different corresponding notions of Cp bundles, infinitely differentiable C∞-bundles and real analytic Cω-bundles.

The most important example of a C∞-vector bundle is the tangent bundle (TM, πTM, M) of a C∞-manifold M. A smooth vector bundle can be characterized by the fact that it admits transition functions as described above which are smooth functions on overlaps of trivializing charts U and V. That is, a vector bundle E is smooth if it admits a covering by trivializing open sets such that for any two such sets U and V, the transition function is a smooth function into the matrix group GL(k,R), which is a Lie group.

Namely, the tangent space Tv(Ex) at any v ∈ Ex can be naturally identified with the fibre Ex itself.

This identification is obtained through the vertical lift vlv: Ex → Tv(Ex), defined as The vertical lift can also be seen as a natural C∞-vector bundle isomorphism p*E → VE, where (p*E, p*p, E) is the pull-back bundle of (E, p, M) over E through p: E → M, and VE := Ker(p*) ⊂ TE is the vertical tangent bundle, a natural vector subbundle of the tangent bundle (TE, πTE, E) of the total space E. The total space E of any smooth vector bundle carries a natural vector field Vv := vlvv, known as the canonical vector field.

More formally, V is a smooth section of (TE, πTE, E), and it can also be defined as the infinitesimal generator of the Lie-group action

As a preparation, note that when X is a smooth vector field on a smooth manifold M and x ∈ M such that Xx = 0, the linear mapping does not depend on the choice of the linear covariant derivative ∇ on M. The canonical vector field V on E satisfies the axioms Conversely, if E is any smooth manifold and V is a smooth vector field on E satisfying 1–4, then there is a unique vector bundle structure on E whose canonical vector field is V. For any smooth vector bundle (E, p, M) the total space TE of its tangent bundle (TE, πTE, E) has a natural secondary vector bundle structure (TE, p*, TM), where p* is the push-forward of the canonical projection p: E → M. The vector bundle operations in this secondary vector bundle structure are the push-forwards +*: T(E × E) → TE and λ*: TE → TE of the original addition +: E × E → E and scalar multiplication λ: E → E. The K-theory group, K(X), of a compact Hausdorff topological space is defined as the abelian group generated by isomorphism classes [E] of complex vector bundles modulo the relation that, whenever we have an exact sequence

KO-theory is a version of this construction which considers real vector bundles.

The famous periodicity theorem of Raoul Bott asserts that the K-theory of any space X is isomorphic to that of the S2X, the double suspension of X.

In algebraic geometry, one considers the K-theory groups consisting of coherent sheaves on a scheme X, as well as the K-theory groups of vector bundles on the scheme with the above equivalence relation.

The two constructs are naturally isomorphic provided that the underlying scheme is smooth.