Wiglaf of Mercia

The causes of the fluctuating fortunes of Mercia and Wessex are a matter of speculation, but it may be that Carolingian support influenced both Ecgberht's ascendancy and the subsequent Mercian recovery.

[7] It was probably Beornwulf whose defeat of the kingdom of Powys and destruction of the fortress of Deganwy are recorded in a Welsh chronicle, the Brut y Tywysogion, in 823, and it is clear that Mercia was still a formidable military power at that time.

In 825 Beornwulf was decisively defeated by Ecgberht, King of Wessex, at the battle of Ellendun, and died the next year in an unsuccessful invasion of East Anglia.

[22] The immediate consequence of Ecgberht's defeat of Beornwulf in 825 at the battle of Ellendun had been the loss of Mercian control over the south-eastern kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, Essex and East Anglia; Beornwulf's and Ludeca's disastrous military expeditions against East Anglia in 826 and 827 also confirmed Mercia's loss of control of that kingdom.

[24] These events led the anonymous scribe who wrote the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle to describe Ecgberht as the eighth bretwalda, or 'Ruler of Britain'.

[28] A charter of 836 has also been cited as evidence that Wiglaf was acting as an independent ruler at that time; it records a council at Croft, in Leicestershire, attended by the Archbishop of Canterbury and eleven bishops, including some from West Saxon sees.

Wiglaf refers to the assembly as "my bishops, duces, and magistrates", indicating not only a recovery of control over his own territory, but some level of authority over the southern church.

[6] Perhaps more surprisingly, given the new strength of Wessex, it appears that the territory along the middle Thames which had formed the heartland of the Gewisse (the precursor people of the 9th-century West Saxon state) remained firmly in Mercian hands.

[29] In the west, either Wiglaf or his successor, Beorhtwulf, brought the Welsh back under Mercian control at some point prior to 853, when a rebellion against Mercia is recorded.

[33] In East Anglia, King Æthelstan minted coins, possibly as early as 827, but more likely c. 830 after Ecgberht's influence was reduced with Wiglaf's return to power in Mercia.

This demonstration of independence on East Anglia's part is not surprising, as it was probably Æthelstan who was responsible for the defeat and death of both Beornwulf and Ludeca.

[6] Both Wessex's sudden rise to power in the late 820s, and the subsequent failure to retain this dominant position, have been examined by historians looking for underlying causes.

[34] The lack of detailed information about Mercian and Wessex administration makes other theories hard to evaluate: for example, it has been suggested that the West Saxons had a stable tributary system that contributed to its success, or that Wessex's mixed Saxon and British population, natural frontiers, and capable administrators were key factors.

The Rhenish and Frankish commercial networks collapsed at some time in the 820s or 830s, and in addition, a rebellion broke out in February 830 against Louis the Pious, the first of a series of internal conflicts that lasted through the 830s and beyond.

In this view, the withdrawal of Frankish influence would have left East Anglia, Mercia and Wessex to find a balance of power not dependent on outside aid.

Ecgberht's influence was certainly reduced after 830, but Mercia never recovered control of the south-east, except possibly for Essex, and East Anglia remained independent.

[37][38] One such charter of Wiglaf's, granting privileges to the monastery of Hanbury in 836, does not exempt the monks from the duty of constructing ramparts, indicating a concern for defence.

The descent of Beorhtwulf is not known, but it appears that dynastic tension was a continuing factor in the Mercian succession, in contrast to Wessex, where Ecgberht established a dynasty that lasted with little disturbance throughout the 9th century.

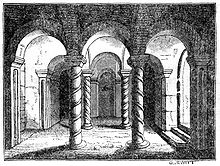

[45] The monastery church on the site at that time was probably constructed by Æthelbald of Mercia to house the royal mausoleum; other burials there include that of Wigstan, Wiglaf's grandson.