Wilhelm Wundt

[7] Born in the German Confederation at a time that was considered very economically stable, Wundt grew up during a period in which the reinvestment of wealth into educational, medical and technological development was commonplace.

– Students (or visitors) who were later to become well known included Vladimir Mikhailovich Bekhterev (Bechterev), Franz Boas, Émile Durkheim, Edmund Husserl, Bronisław Malinowski, George Herbert Mead, Edward Sapir, Ferdinand Tönnies, Benjamin Lee Whorf.

[21] According to Wirth (1920), over the summer of 1920, Wundt "felt his vitality waning ... and soon after his eighty-eighth birthday, he died ... a gentle death on the afternoon of Tuesday, August 3" (p.

Wundt considered that reference to the subject (Subjektbezug), value assessment (Wertbestimmung), the existence of purpose (Zwecksetzung), and volitional acts (Willenstätigkeit) to be specific and fundamental categories for psychology.

Using the example of volitional acts, Wundt describes possible inversion in considering cause and effect, ends and means, and explains how causal and teleological explanations can complement one another to establish a co-ordinated consideration.

Leibniz described apperception as the process in which the elementary sensory impressions pass into (self-)consciousness, whereby individual aspirations (striving, volitional acts) play an essential role.

The fundamental task is to work out a comprehensive development theory of the mind – from animal psychology to the highest cultural achievements in language, religion and ethics.

Unlike other thinkers of his time, Wundt had no difficulty connecting the development concepts of the humanities (in the spirit of Friedrich Hegel and Johann Gottfried Herder) with the biological theory of evolution as expounded by Charles Darwin.

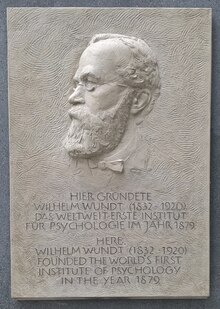

The initial conceptual outlines of the 30-year-old Wundt (1862, 1863) led to a long research program, to the founding of the first Institute and to the treatment of psychology as a discipline, as well as to a range of fundamental textbooks and numerous other publications.

As a result of his medical training and his work as an assistant to Hermann von Helmholtz, Wundt knew the benchmarks of experimental research, as well as the speculative nature of psychology in the mid-19th century.

The observed differences were intended to contribute towards supporting Wundt's theory of emotions with its three dimensions: pleasant – unpleasant, tense – relaxed, excited – depressed.

Wundt (1888) critically analysed the, in his view, still disorganised intentions of Lazarus and Steinthal and limited the scope of the issues by proposing a psychologically constituted structure.

The topics range from agriculture and trade, crafts and property, through gods, myths and Christianity, marriage and family, peoples and nations to (self-)education and self-awareness, science, the world and humanity.

Motives frequently quoted in cultural development are: division of labour, ensoulment, salvation, happiness, production and imitation, child-raising, artistic drive, welfare, arts and magic, adornment, guilt, punishment, atonement, self-education, play, and revenge.

Kant had argued against the assumption of the measurability of conscious processes and made a well-founded, if very short, criticism of the methods of self-observation: regarding method-inherent reactivity, observer error, distorting attitudes of the subject, and the questionable influence of independently thinking people,[66] but Wundt expressed himself optimistic that methodological improvements could be of help here.

In the introduction to his Grundzüge der physiologischen Psychologie in 1874, Wundt described Immanuel Kant and Johann Friedrich Herbart as the philosophers who had the most influence on the formation of his own views.

Wundt's position was decisively rejected by several Christianity-oriented psychologists and philosophers as a psychology without soul, although he did not use this formulation from Friedrich Lange (1866), who was his predecessor in Zürich from 1870 to 1872.

"Metaphysics is the same attempt to gain a binding world view, as a component of individual knowledge, on the basis of the entire scientific awareness of an age or particularly prominent content.

[99] Wundt interpreted intellectual-cultural progress and biological evolution as a general process of development whereby, however, he did not want to follow the abstract ideas of entelechy, vitalism, animism, and by no means Schopenhauer's volitional metaphysics.

He believed that the source of dynamic development was to be found in the most elementary expressions of life, in reflexive and instinctive behaviour, and constructed a continuum of attentive and apperceptive processes, volitional or selective acts, up to social activities and ethical decisions.

While logic, the doctrine of categories, and other principles were discussed by Wundt in a traditional manner, they were also considered from the point of view of development theory of the human intellect, i.e. in accordance with the psychology of thought.

The university's stock consists of 6,762 volumes in western languages (including bound periodicals) as well as 9,098 special print runs and brochures from the original Wundt Library.

At the start of the First World War, Wundt, like Edmund Husserl and Max Planck, signed the patriotic call to arms as did about 4,000 professors and lecturers in Germany, and during the following years he wrote several political speeches and essays that were also characterized by the feeling of a superiority of German science and culture.

The psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin described the pioneering spirit at the new Leipzig Institute in this fashion: "We felt that we were trailblazers entering virgin territory, like creators of a science with undreamt-of prospects.

One could consider Wundt's gradual concurrence with Kant's position, that conscious processes are not measurable on the basis of self-observation and cannot be mathematically formulated, to be a major divergence.

None of his Leipzig assistants and hardly any textbook authors in the subsequent two generations have adopted Wundt's broad theoretical horizon, his demanding scientific theory or the multi-method approach.

The XXII International Congress for Psychology in Leipzig in 1980, i.e. on the hundredth jubilee of the initial founding of the institute in 1879, stimulated a number of publications about Wundt, also in the US[120] Very little productive research work has been carried out since then.

Wundt's more demanding, sometimes more complicated and relativizing, then again very precise style can also be difficult – even for today's German readers; a high level of linguistic competence is required.

He tried to connect the fundamental controversies of the research directions epistemologically and methodologically by means of a co-ordinated concept – in a confident handling of the categorically basically different ways of considering the interrelations.

Here, during the founding phase of university psychology, he already argued for a highly demanding meta-science meta-scientific reflection – and this potential to stimulate interdisciplinarity und perspectivism (complementary approaches) has by no means been exhausted.

Southwest University Chongqing, China