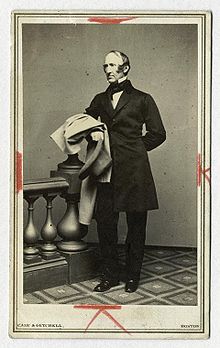

Wendell Phillips

[1] According to another Black attorney, Archibald Grimké, as an abolitionist leader he is ahead of William Lloyd Garrison and Charles Sumner.

[8][9] Like many of Phillips' fellow abolitionists who honored the free-produce movement, he condemned the purchase of cane sugar and clothing made of cotton, since both were produced by the labor of slaves.

[14] In 1845, in an essay titled "No Union With Slaveholders", he argued that the country would be better off, and not complicit in their guilt, if it let the slave states secede: The experience of the fifty years...shows us the slaves trebling in numbers—slaveholders monopolizing the offices and dictating the policy of the Government—prostituting the strength and influence of the Nation to the support of slavery here and elsewhere—trampling on the rights of the free States, and making the courts of the country their tools.

The trial of fifty years only proves that it is impossible for free and slave States to unite on any terms, without all becoming partners in the guilt and responsible for the sin of slavery.

[15] Bostonians gathered at Faneuil Hall to discuss Elijah P. Lovejoy's murder by a mob outside his abolitionist newspaper's office in Alton, Illinois, on November 7.

At Faneuil Hall, Massachusetts attorney general James T. Austin defended the pro-slavery mob, comparing their actions to 1776 patriots who fought against the British and declaring that Lovejoy "died as the fool dieth!

They made important connections and Ann wrote of them meeting Elizabeth Pease and being particularly impressed by the Quaker abolitionist Richard D. Webb.

Phillips' new wife was one of a number of female delegates, who included Lucretia Mott, Mary Grew, Sarah Pugh, Abby Kimber, Elizabeth Neall and Emily Winslow.

According to the history of the women's rights movement of Susan B. Anthony's and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Phillips spoke as the convention opened, scolding the organizers for precipitating an unnecessary conflict: When the call reached America we found that it was an invitation to the friends of the slave of every nation and of every clime.

[citation needed] In 1854, Phillips was indicted for his participation in the celebrated attempt to rescue Anthony Burns, a captured fugitive slave, from a jail in Boston.

On the eve of the Civil War, Phillips gave a speech at the New Bedford Lyceum in which he defended the Confederate States' right to secede: A large body of people, sufficient to make a nation, have come to the conclusion that they will have a government of a certain form.

This position was rejected by nationalists like Abraham Lincoln, who insisted on holding the Union together while gradually ending slavery.

[19] Disappointed with what he regarded as Lincoln's slow action, Phillips opposed his reelection in 1864, breaking with Garrison, who supported a candidate for the first time.

[citation needed] In the July 3, 1846, issue of The Liberator he called for securing women's rights to their property and earnings as well as to the ballot.

He wrote: I have always thought that the first right restored to woman would be that of the full and unfettered control of all her property and earnings, whether she were married or unmarried.

He was a close adviser of Lucy Stone, and a major presence at most of the conventions, for which he wrote resolutions defining the movement's principles and goals.

[25] Phillips's philosophical ideal was mainly self-control of the animal, physical self by the human, rational mind, although he admired martyrs like Elijah Lovejoy and John Brown.

[further explanation needed] The Puritan ideal of a Godly Commonwealth through a pursuit of Christian morality and justice, however, was the main influence on Phillips's nationalism.

[citation needed] As Northern victory in the Civil War seemed more imminent, Phillips, like many other abolitionists, turned his attention to the questions of Reconstruction.

In 1864, he gave a speech at the Cooper Institute in New York arguing that enfranchisement of freedmen should be a necessary condition for the readmission of Southern states to the Union.

"[28] As Radical Republicans in Congress broke with Johnson and pursued their own Reconstruction policies through the Freedmen's Bureau bills and the Civil Rights Act of 1866, their views converged increasingly with Phillips'.

[31] As the Reconstruction era came to a close, Phillips increased his attention to other issues, such as women's rights, universal suffrage, temperance, and the labor movement.

[32] Phillips was also active in efforts to gain equal rights for Native Americans, arguing that the Fifteenth Amendment also granted citizenship to Indians.

[34] Public opinion turned against Native American advocates after the Battle of the Little Bighorn in July 1876, but Phillips continued to support the land claims of the Lakota (Sioux).

[39] On February 12, a memorial service was held at the Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church on Sullivan Street in New York City.

In July 1915, a monument was erected in Boston Public Garden to commemorate Phillips, inscribed with his words: "Whether in chains or in laurels, liberty knows nothing but victories."

[44] A phrase from his speech of January 20, 1861, "I think the first duty of society is justice,"[45] sometimes wrongly attributed to Alexander Hamilton, appears on various courthouses around the United States, including in Nashville, Tennessee.