Alfred Moore Waddell

This event is considered to be the only successful coup d'état to have taken place on U.S. soil, and helped to initiate an era of severe racial segregation and disenfranchisement of African-Americans throughout the South.

[3] He attended Bingham's School and Caldwell Institute before enrolling in the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, graduating in 1853.

In July 1860, Waddell purchased the most influential Whig newspaper in the Cape Fear region, the Wilmington Daily Herald, and used it as a platform to promote his views opposing secession.

"[4] During The Civil War, Waddell joined the Confederacy as an adjutant, in 1861, rising to the rank of lieutenant colonel in the Third Cavalry, which later became known as the Forty-First North Carolina Regiment.

[4] Waddell remained active in the Democratic Party after his defeat, becoming a highly sought after political speaker and campaigner.

[2] He was a delegate to the Democratic National Conventions in 1880, where he supported Union General Winfield Scott Hancock for president and was also a member of the platform committee.

[4] Following The Civil War, in 1868, North Carolina ratified the 14th Amendment, resulting in the recognition of Reconstruction, and in the state legislature and governorship falling under Republican rule.

Democrats greatly resented this "radical" change, which they deemed as being brought about by blacks, Unionist carpetbaggers, and race traitors.

[7] As the Democrats chipped away at Republican rule, things came to a head with the 1876 gubernatorial campaign of Zebulon B. Vance, a former Confederate soldier and governor.

[8] However, in that region, poor white cotton farmers, fed up with the capitalism of big banks and railroad companies, had aligned themselves with the labor movement.

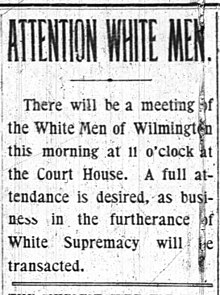

[12] Simmons created a speakers bureau, stacking it with talented orators who he could deploy to deliver the message across the state.

[9] Leading up to the November election, in August 1898, white men began to abandon the Fusion coalition when Alexander Manly, the owner of Wilmington's sole black newspaper, "The Daily Record," wrote an editorial responding to a speech supporting lynchings, by printing that many white women were not raped by black men, but willingly slept with them.

[9] This provided an opening for Democrats, now referring to themselves as "The "white man's party," as "evidence" supporting their claims of predatory blacks.

[15] However, Waddell set himself apart from the other speakers through his rousing ability to incite through propaganda, which he cemented with a blistering closing to his speech when he proclaimed, "We will never surrender to a ragged raffle of Negroes, even if we have to choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses.

[13] Shortly after delivering it, The Red Shirts began riding through the state, on horseback, terrorizing black citizens and voters.

The committee was tasked with "directing the execution of the provisions of the resolutions" within "The White Declaration of Independence," a document authored by the Secret Nine which called for the removal of voting rights for blacks, and for the overthrow of the newly elected interracial government.

"[9][16]Democrats won the election in Wilmington by 6,000 votes, a sizable shift from the Fusion Party's 5,000-vote edge just two years prior.

However, the Fusion Party remained intact in Wilmington, the North Carolina city with the greatest concentration of black wealth and economic power.

"[17] He proclaimed, to the raucous crowd of 600, that the U.S. Constitution "did not anticipate the enfranchisement of an ignorant population of African origin," that "never again will white men of New Hanover County permit black political participation" that "the Negro stop antagonizing our interests in every way, especially by his ballot," and that the city "give to white men a large part of the employment heretofore given to Negroes.

[9][10][19] On November 26, 1898, Collier's Weekly published an article in which Waddell wrote about the government overthrow entitled, "The Story of The Wilmington, North Carolina, Race Riots" Despite vowing to "choke the Cape Fear River with carcasses," and the fact that some members of the white mob posed for a photograph in front of the charred remnants of "The Daily Record," Waddell painted himself in the article as a reluctant non-violent leader – or accidental hero – "called upon" to lead under "intolerable conditions."

He painted the white mob not as murderous lawbreakers, but as peaceful, law-abiding citizens who simply wanted to restore law and order.

He also portrayed any violence committed by whites as either being accidental or executed in self-defense, effectively laying blame on both sides:[9][10] "Demand was made for the negroes to reply to our ultimatum to them [to destroy the black newspaper and leave town forever, or have it destroyed/be removed by force], and their reply was delayed or sent astray (whether purposely or not, I do not know), and that caused all the trouble.

when so conservative a man as Colonel Waddell talks about filling the river with dead niggers, I want to get out of town!'

"[19][21]Waddell's account, and his effective label of "race riot," ignored the fact that the overthrow was a carefully planned conspiracy, turned the coup into an event that "spontaneously happened," helped usher in the Solid South, and set the precedent for the application of the term "race riot," that is still used today.