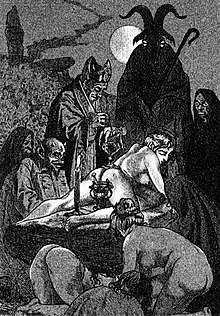

Witches' Sabbath

A compilation of German folklore by Jakob Grimm in the 1800s (Kinder und HausMärchen, Deutsche Mythologie) seems to contain no mention of hexensabbat or any other form of the term sabbat relative to fairies or magical acts.

In contrast to German and English counterparts, French writers (including Francophone authors writing in Latin) used the term more frequently, albeit still relatively rarely.

[16] In 1668, a late date relative to the major European witch trials, German writer Johannes Praetorius published "Blockes-Berges Verrichtung", with the subtitle "Oder Ausführlicher Geographischer Bericht/ von den hohen trefflich alt- und berühmten Blockes-Berge: ingleichen von der Hexenfahrt/ und Zauber-Sabbathe/ so auff solchen Berge die Unholden aus gantz Teutschland/ Jährlich den 1.

[17] As indicated by the subtitle, Praetorius attempted to give a "Detailed Geographical Account of the highly admirable ancient and famous Blockula, also about the witches' journey and magic sabbaths".

Conventibus is the word Spee uses most frequently to denote a gathering of witches, whether supposed or real, physical or spectral, as seen in the first paragraph of question one of his book.

First, belief in the real power of witchcraft grew during the late medieval and early-modern Europe as a doctrinal view in opposition to the canon Episcopi gained ground in certain communities.

[24] Bristol University's Ronald Hutton has encapsulated the witches' sabbath as an essentially modern construction, saying: [The concepts] represent a combination of three older mythical components, all of which are active at night: (1) A procession of female spirits, often joined by privileged human beings and often led by a supernatural woman; (2) A lone spectral huntsman, regarded as demonic, accursed, or otherworldly; (3) A procession of the human dead, normally thought to be wandering to expiate their sins, often noisy and tumultuous, and usually consisting of those who had died prematurely and violently.

Norman Cohn argued that they were determined largely by the expectations of the interrogators and free association on the part of the accused, and reflect only popular imagination of the times, influenced by ignorance, fear and religious intolerance towards minority groups.

[29] Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches' Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil's anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, lepers, Muslims and Jews.

[30] The term is the same as the normal English word "Sabbath" (itself a transliteration of Hebrew "Shabbat", the seventh day, on which the Creator rested after creation of the world), referring to the witches' equivalent to the Christian day of rest; a more common term was "synagogue" or "synagogue of Satan"[31] possibly reflecting anti-Jewish sentiment, although the acts attributed to witches bear little resemblance to the Sabbath in Christianity or Jewish Shabbat customs.

Other historians, including Carlo Ginzburg, Éva Pócs, Bengt Ankarloo and Gustav Henningsen hold that these testimonies can give insights into the belief systems of the accused.

[35]Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness.

In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as Apuleius, is the use of unguents conferring the power of "flight" and "shape-shifting.

], permitting not only an assessment of their likely pharmacological effects – based on their various plant (and to a lesser extent animal) ingredients – but also the actual recreation of and experimentation with such fat or oil-based preparations.

For a long time the only dissenting voices were those of the people who, referring back to the Canon episcopi, saw witches and sorcerers as the victims of demonic illusion.

In the sixteenth century scientists like Cardano or Della Porta formulated a different opinion : animal metamorphoses, flights, apparitions of the devil were the effect of malnutrition or the use of hallucinogenic substances contained in vegetable concoctions or ointments...But no form of privation, no substance, no ecstatic technique can, by itself, cause the recurrence of such complex experiences...the deliberate use of psychotropic or hallucinogenic substances, while not explaining the ecstasies of the followers of the nocturnal goddess, the werewolf, and so on, would place them in a not exclusively mythical dimension.– in short, a substrate of shamanic myth could, when catalysed by a drug experience (or simple starvation), give rise to a 'journey to the Sabbath', not of the body, but of the mind.

[40] The alkaloids Atropine, Hyoscyamine and Scopolamine present in these Solanaceous plants are not only potent and highly toxic hallucinogens, but are also fat-soluble and capable of being absorbed through unbroken human skin.