Wittenberg interpretation of Copernicus

One such place that these debates existed was the University of Wittenberg which was home to many astronomers, astrologists and mathematicians, such as Erasmus Reinhold, Philip Melanchthon, Caspar Peucer, Georg Rheticus, and Albrecht Hohenzollern.

[2] The work of such figures became known as the Wittenberg Interpretation, which historians recognise as important in fostering acceptance for the heliocentric explanation of the universe, and the wider shift of public views over time; and the beginning of the Scientific Revolution.

His teachings included Ptolemy's Libri de judiciis astrologicis, and emphasized a connection between astronomical events and God.

[4] In 1536, Melanchthon appointed Georg Joachim Rheticus and Erasmus Reinhold, two of his previous students, to chairs of Lower and Higher Mathematics.

Peucer mainly cited Copernican quantitative material in order to help explain celestial motions, even though it was different from scripture, and to discuss absolute distances of the sun, moon and earth.

[6] Notably, the members of the circle admired the teachings of Italian scholars, with Rheticus supporting the views of Girolamo Cardano, and Peucer being well read in the works of Pietro Pomponazzi.

[8] He strongly believed that unusual events that did not follow the natural laws was due to divine intervention either by God or the devil.

[8] Copernicus's heliocentric theory was inspired by the research of Aristotle and firmly followed the laws of natural science without consideration for divine intervention.

[4] Peucer thought that the Copernican theory, heliocentric model could be interpreted in a geocentric way without changing the original hypotheses.

[4] Peucer's work Hypotyposes orbium coelestium states that the Copernican model could be utilized if two more spheres were added.

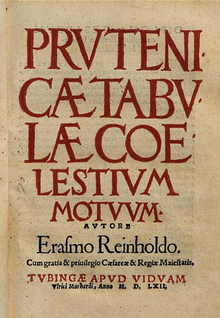

[10] Reinhold initially became acquainted with Copernican theory through the writings of Georg Joachim Rheticus, an astronomer and colleague who also worked closely with Melanchthon at the University.

Before De Revolutionibus orbium coelestium was published, Reinhold gained information regarding Copernican theory, specifically regarding the movement of the moon, from Narratio prima.

In additional annotations, Reinhold continually mentions how new Copernican theory simplifies astronomical motion by erasing the need for an equant, an idea previously introduced by the geocentric model of the Ptolemaic system.

[4] This new idea, the rejection of the equant, is the source of Reinhold’s praise of Copernicus and Copernican theory, as it simplifies planetary motion and in his opinion, allows for the future of astronomy to move forward in a smoother, less confusing or cluttered manner.

[4] After the publication of De revolutionibus orbium coelestium in 1543, Reinhold remained relatively neutral on the issue of a heliocentric versus a geocentric cosmos.

However, he wanted to recalculate and provide clean and simple-to-read tables based on the new ideas of motion presented in De revolutioninus.

Copernicus developed his heliocentric theory after realizing that the retrograde motion of the planets could be explained much better without epicycles, with the Earth orbiting the Sun rather than the other way around.

Rheticus believed that the heliocentric universe should be adopted because it could explain the phenomena of the precession of the equinoxes and the change in the obliquity of the ecliptic.

If the Sun was the center of the deferents of the planets, it allowed the circles in the universe to revolve uniformly and regularly, it united all the spheres into one system, and it was a simpler model with fewer explanations necessary.

The book emphasized the demonstration of a system in the necessary interconnexity of the relative distance and periods of the planets, a problem in the Copernican theory that the textbooks did not mention.

[4] Rheticus claimed that a common measure was established to explain how the planets were geometrically aligned and arranged so that no immense interval was left between one and the other.

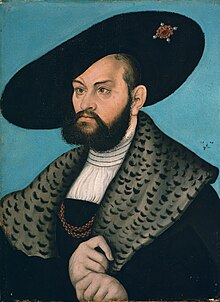

It is somewhat surprising that Albrecht remained so interested and invested in the sciences, as there were many debates at the time as to whether or not the new astronomical considerations went against the views of the world in the Bible.

As he was a Protestant/Lutheran, these men knew that he had the power to protect them from being charged with the crime of spreading beliefs that went against the current interpretation of the Bible.

Despite the fact that Albrecht had never heard of this new mathematician before, he obliged: he sent back a “lisbonino”, which was a gold coin that was meant for showcasing, rather than being used as currency.

[4][17] Most of the astronomers and mathematicians at Wittenberg (Melanchthon, Peucer, Reinhold) took a more moderate stance toward the Copernican theory and only accepted parts of it to be true.

Overall, the Wittenberg Interpretation changed the way astronomers and mathematicians viewed the heliocentric and geocentric models of the cosmos and how it was taught throughout German universities.