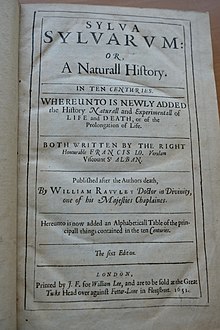

Works by Francis Bacon

Francis Bacon, 1st Viscount St Alban, KC (22 January 1561 – 9 April 1626) was an English philosopher, statesman, scientist, lawyer, jurist, author, and pioneer of the scientific method.

His demand for a planned procedure of investigating all things natural marked a new turn in the rhetorical and theoretical framework for science, much of which still surrounds conceptions of proper methodology today.

Another admonition was concerning the ends of science: that mankind should seek knowledge not for pleasure, contention, superiority over others, profit, fame, or power, but for the benefit and use of life, and that they perfect and govern it in charity.

Nevertheless, Bacon contrasted the new approach of the development of science with that of the Middle Ages: Men have sought to make a world from their own conception and to draw from their own minds all the material which they employed, but if instead of doing so, they had consulted experience and observation, they would have the facts and not opinions to reason about, and might have ultimately arrived at the knowledge of the laws which govern the material world.And he spoke of the advancement of science in the modern world as the fulfilment of a prophecy made in the Book of Daniel that said: "But thou, O Daniel, shut up the words, and seal the book, even to the time of the end: many shall run to and fro, and knowledge shall be increased" (see "Of the Interpretation of Nature").

[1][page needed] According to author Nieves Mathews, the promoters of the French Reformation misrepresented Bacon by deliberately mistranslating and editing his writings to suit their anti-religious and materialistic concepts, which action would have carried a highly influential negative effect on his reputation.

For this purpose of obtaining knowledge of and power over nature, Bacon outlined in this work a new system of logic he believed to be superior to the old ways of syllogism, developing his scientific method, consisting of procedures for isolating the formal cause of a phenomenon (heat, for example) through eliminative induction.

These are called "Idols" (idola),[a] and are of four kinds: About which, he stated: If we have any humility towards the Creator; if we have any reverence or esteem of his works; if we have any charity towards men or any desire of relieving their miseries and necessities; if we have any love for natural truths; any aversion to darkness, any desire of purifying the understanding, we must destroy these idols, which have led experience captive, and childishly triumphed over the works of God; and now at length condescend, with due submission and veneration, to approach and peruse the volume of the creation; dwell some time upon it, and bringing to the work a mind well purged of opinions, idols, and false notions, converse familiarly therein.

Bacon's concern of the idols of the marketplace is words no longer correspond to Nature but instead come to refer to intangible concepts and so possess an artificial worth.

About which Professor Benjamin Farrington stated: " while it is a fact that he labored to distinguish the realms of faith and knowledge, it is equally true that he thought one without the other useless".

In this work, which is divided into two books, Bacon starts giving philosophical, civic and religious arguments for the engaging in the aim of advancing learning.

In this work of 1603, an argument for the progress of knowledge, Bacon considers the moral, religious and philosophical implications and requirements for the advancement of learning and the development of science.

[18]This quote from the Book of Daniel appears also in the title page of Bacon's Instauratio Magna and Novum Organum, in Latin: "Multi pertransibunt & augebitur scientia".

He opens, in the Preface, stating his hope and desire that the work would contribute to the common good, and that through it the physicians would become "instruments and dispensers of God's power and mercy in prolonging and renewing the life of man".

Released in 1627, this was his creation of an ideal land where "generosity and enlightenment, dignity and splendor, piety and public spirit" were the commonly held qualities of the inhabitants of Bensalem.

The name "Bensalem" means "Son of Peace",[b] having obvious resemblance with "Bethlehem" (birthplace of Jesus), and is referred to as "God's bosom, a land unknown", in the last page of the work.

[24] After that incident, these travellers in a distant water finally reached the island of Bensalem, where they found a fair and well-governed city, and were received kindly and with all humanity by Christian and cultured people, who had been converted centuries before by a miracle wrought by Saint Bartholomew, twenty years after the Ascension of Jesus, by which the scriptures had reached them in a mysterious ark of cedar floating on the sea, guarded by a gigantic pillar of light, in the form of a column, over which was a bright cross of light.

Namely: 1) the end of their foundation; 2) the preparations they have for their works; 3) the several employments and function whereto their fellows are assigned; 4) and the ordinances and rites which they observe.

[24] In describing the ordinances and rites observed by the scientists of Salomon's House, its Head said: "We have certain hymns and services, which we say daily, of Lord and thanks to God for His marvelous works; and some forms of prayer, imploring His aid and blessing for the illumination of our labors, and the turning of them into good and holy uses".

The Essays were praised by his contemporaries and have remained in high repute ever since; 19th-century literary historian Henry Hallam wrote that "They are deeper and more discriminating than any earlier, or almost any later, work in the English language".

[36] He retells thirty-one ancient fables, suggesting that they contain hidden teachings on varied issues such as morality, philosophy, religion, civility, politics, science, and art.

In his interpretation of the myth, Bacon finds Proteus to symbolize all matter in the universe: "For the person of Proteus denotes matter, the oldest of all things, after God himself; that resides, as in a cave, under the vast concavity of the heavens" Much of Bacon's explanation of the myth deals with Proteus's ability to elude his would-be captors by shifting into various forms: "But if any skillful minister of nature shall apply force to matter, and by design torture and vex it…it, on the contrary…changes and transforms itself into a strange variety of shapes and appearances…so that at length, running through the whole circle of transformations, and completing its period, it in some degree restores itself, if the force be continued.

In Temporis Partus Masculus (The Masculine Birth of Time, 1603), a posthumously published text, Bacon first writes about the relationship between science and religion.

Through the voice of the teacher, Bacon demands a split between religion and science: "By mixing the divine with the natural, the profane with the sacred, heresies with mythology, you have corrupted, O you sacrilegious impostor, both human and religious truth.

He composed an art or manual of madness and made us slaves to words.” As Bacon develops further throughout his scientific treatises, Aristotle's crime of duping the intellect into the belief that words possess an intrinsic connection with Nature confused the subjective and the objective.

The text identifies the goal of the elderly guide's instructions as the student's ability to engage in a (re)productive relationship with Nature: “My dear, dear boy, what I propose is to unite you with things themselves in a chaste, holy, and legal wedlock.” Although, as the text presents it, the student has not yet reached that point of intellectual and sexual maturity, the elderly guide assures him that once he has properly distanced himself from Nature he will then be able to bring forth “a blessed race of Heroes and Supermen who will overcome the immeasurable helplessness and poverty of the human race.”[41] A collection of religious meditations by Lord Bacon, published in 1597.

Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker have argued, based on this treatise, that Bacon was not as idealistic as his utopian works suggest, rather that he was what might today be considered an advocate of genocidal eugenics.

They see in it a defense of the elimination of detrimental societal elements by the English and compared this to the endeavors of Hercules while establishing a civilized society in ancient Greece.

[...] (Concerning the establishment of colonies in the 'New World') To make no extirpation of the natives under the pretense of planting religion: God surely will no way be pleased with such sacrifices.

[46]Published in 1625 and considered to be the last of his writings, Bacon translated 7 of the Psalms of David (numbers 1, 12, 90, 104, 126, 137, 149) to English in verse form, in which he shows his poetical skills.

[49]Basil Montagu, a later British jurist influenced by his legal work, characterised him as a "cautious, gradual, confident, permanent reformer", always based on his "love of excellence".