Propaganda in World War I

According to Eberhard Demm and Christopher H. Sterling: Propaganda could be used to arouse hatred of the foe, warn of the consequences of defeat, and idealize one's own war aims in order to mobilize a nation, maintain its morale, and make it fight to the end.

Censorship rules placed strict restrictions on frontline journalism and reportage, a process that continues to affect the historical record — for instance, possibly due to image concerns, there is no known visual evidence of American shotgun use during the war.

When Wilhelm II declared a state of war in Germany on July 31, the commanders of the army corps (German: Stellvertretende Generalkommandos) took control of the administration, including implementing a policy of press censorship, which was carried out under Walter Nicolai.

[6] Censorship regulations were put in place in Berlin, with the War Press Office fully controlled by the Army High Command.

D) The rhetoric exalted Germany's historic mission to promote high culture and true civilization, celebrating the slogan "work, order, duty" over the enemy's "liberty, equality, fraternity."

Germany needed land to expand, as an outlet for its surplus population, talent, organizing ability, financial capital, and manufacturing output.

Russian press operating in the Caucasus had been reporting on a "really intolerable situation" in Anatolia since before the formal commencement of hostilities with the Ottoman Empire.

They had, starting in 1912, elected to again appeal to international diplomacy instead of relying on their own armed struggle.The most influential man behind the propaganda in the United States was President Woodrow Wilson.

[18] Aside from the restoration of freedom in Europe in countries that were suppressed by the power of Germany, Wilson's Fourteen Points called for transparency regarding discussion of diplomatic matters, the free navigation of the seas in peace and in war, and equal trade conditions among all nations.

[8] Wilson's points inspired audiences around the world and greatly strengthened the belief that Britain, France, and America were fighting for noble goals.

[8] The committee, headed by the former investigative journalist George Creel, emphasized the message that America's involvement in the war was entirely necessary for achieving the salvation of Europe from the German and enemy forces.

[8] In his book titled How we Advertised America, Creel states that the committee was called into existence to make World War I a fight that would be a "verdict for mankind.

Creel set out systematically to reach every person in the United States multiple times with patriotic information about how the individual could contribute to the war effort.

Creel set up divisions in his new agency to produce and to distribute innumerable copies of pamphlets, newspaper releases, magazine advertisements, films, school campaigns, and the speeches of the Four Minute Men.

[25] Cinemas were widely attended, and the CPI trained thousands of volunteer speakers to make patriotic appeals during four-minute breaks, which were needed to change reels.

The speakers attended training sessions through local universities and were given pamphlets and speaking tips on a wide variety of topics, such as buying Liberty bonds, registering for the draft, rationing food, recruiting unskilled workers for munitions jobs, and supporting Red Cross programs.

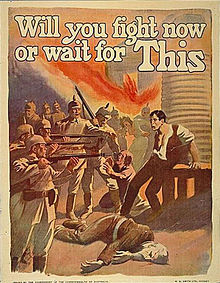

[37] Atrocity propaganda exploiting sensational stories of rape, mutilation, and wanton murder of prisoners by the Germans filled the Allied press.

[39] Graphic illustrations, accompanied by first-hand testimonies that described the crimes as savagely unjust, were compelling reminders to justify the war.

[39] Other forms of atrocity propaganda depicted the alternative to war to involve German occupation and domination,[40] which was regarded as unacceptable across the political spectrum.

That would appear to be a form of censorship, but the newspapers of Britain, which were effectively controlled by the media barons of the time, were happy to follow and printed headlines that were designed to stir up emotions, regardless of whether or not they were accurate.

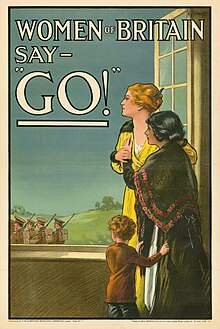

[1] In 1914, the British Army was made up of not only professional soldiers but also volunteers and so the government relied heavily on propaganda as a tool to justify the war to the public eye.

[1] Another message that was deeply embedded in national sentiment the religious symbolism of St George, who was shown slaying a dragon, which represented the German forces.

[46] Wartime diplomacy focused on five issues: propaganda campaigns to shape news reports and commentary; defining and redefining the war goals, which became harsher as the war went on; luring neutral nations (Italy, the Ottoman Empire, Bulgaria and Romania) into the coalition by offering slices of enemy territory; and encouragement by the Allies of nationalistic minority movements within the Central Powers, especially among Czechs, Poles, and Arabs.

[47] As soon as the war began, Britain cut Germany's undersea communication cables as a way to ensure that the Allies had a monopoly on the most expedient means of transmitting news from Europe to press outlets in the United States.

[48] In 1914, a secret British organization, Wellington House, was set up and called for journalists and newspaper editors to write articles that sympathised with Britain as a way to counter statements that were made by the enemy.

[48] Wellington House implemented the action not only through favourable reports in the press of neutral countries but also by publishing its own newspapers, which were circulated around the globe.

[50] British propaganda played on the fears of the country's citizens by depicting the German Army as a ravenous force that horrified towns and cities, raped women and tore families apart.

[50] In the Ottoman Empire, the United States, and other countries, women were encouraged to enter the workforce since the number of men kept shrinking during the war.

[52] In wartime fiction published by magazines like McClure's, female characters were cast as either virtuous self-sacrificing homemakers sending the men to war or unethical and selfish women who were usually drunk and too wealthy to be restrained by social mores.

McClure's Win-the-War Magazine included contributions from authors Porter Emerson Browne and Dana Gatlin, recognized by scholars for their sentimental style of writing propaganda fiction employing stereotyped female characters.