Wulfhere of Mercia

His accession marked the end of Oswiu of Northumbria's overlordship of southern England, and Wulfhere extended his influence over much of that region.

Wulfhere came to the throne when Mercian nobles organized a revolt against Northumbrian rule in 658 and drove out Oswiu's governors.

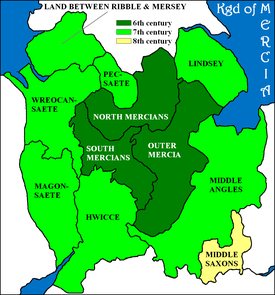

[2] Little is known about the origins of the kingdom of Mercia, in what is now the English Midlands, but according to genealogies preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and the Anglian collection the early kings were descended from Icel; the dynasty is therefore known as the Iclingas.

[3] The earliest Mercian king about whom definite historical information has survived is Penda of Mercia, Wulfhere's father.

[4] According to Bede's Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum, a history of the English church, there were seven early Anglo-Saxon rulers who held imperium, or overlordship, over the other kingdoms.

[5] The fifth of these was Edwin of Northumbria, who was killed at the Battle of Hatfield Chase by a combined force including Cadwallon, a British king of Gwynedd and Penda.

Within a year Oswald killed Cadwallon and reunited the kingdoms, and subsequently re-established Northumbrian hegemony over the south of England.

[22] An 11th-century history of St. Peter's Monastery in Gloucester names two other women, Eadburh and Eafe, as queens of Wulfhere, but neither claim is plausible.

[26] The northern portion was kept under direct Northumbrian control; the southern kingdom was given to Penda's son Peada, who had married Oswiu's daughter Ealhflæd ca 653.

[5] Overlordship was a common relationship between kingdoms at this time, often taking the form of a lesser king under the domination of a stronger one.

This attempt to establish close control of Mercia failed in 658 when three Mercian leaders, Immin, Eafa and Eadbert, rebelled against the Northumbrians.

[32] Bede does not list him as one of the rulers who exercised imperium, but modern historians consider that the rise to primacy of the kingdom of Mercia began in his reign.

The monastery had initially been endowed by Peada; for the dedication of Wulfhere's gift both Archbishop Deusdedit (died 664), and Bishop Jaruman (held office from 663), were present.

This decision was probably a reaction to the advance of the Mercians into the traditional heartland of the West Saxons, leaving Dorchester dangerously close to the border.

He subsequently gave both the island and the territory of the Meonware, which lay along the river Meon, on the mainland north of the Isle of Wight, to his godson King Æthelwealh of the South Saxons.

[50] In the early 670s, Cenwealh of Wessex died, and perhaps as a result of the stress caused by Wulfhere's military activity the West Saxon kingdom fragmented and came to be ruled by underkings, according to Bede.

A decade after Wulfhere's death, the West Saxons under Cædwalla began an aggressive expansion to the east, reversing much of the Mercian advance.

His wife was Queen Eafe, the daughter of Eanfrith of the Hwicce, a tribe whose territory lay to the southwest of Mercia.

Swithhelm of the East Saxons also died in 664; he was succeeded by his two sons, Sigehere and Sæbbi, and Bede describes their accession as "rulers ... under Wulfhere, king of the Mercians".

[42] A plague the same year caused Sigehere and his people to recant their Christianity, and according to Bede, Wulfhere sent Jaruman, the bishop of Lichfield, to reconvert the East Saxons.

This becomes even clearer in the next few years, as some time between 665 and 668 Wulfhere sold the see of London to Wine, who had been expelled from his West Saxon bishopric by Cenwealh.

It has been speculated that Wulfhere acted as the effective ruler of Kent in the interregnum between Egbert's death and Hlothhere's accession.

It was ruled by Egbert until the early 670s, when a charter shows Wulfhere confirming a grant made to Bishop Eorcenwald by Frithuwold, a sub-king in Surrey, which may have extended north into modern Buckinghamshire.

A witness named Frithuric is recorded on a charter in the reign of Wulfhere's successor, Æthelred, making a grant to the monastery of Peterborough, and the alliteration common in Anglo-Saxon dynasties has led to speculation that the two men may have both come from a Middle Anglian dynasty, with Wulfhere perhaps having placed Frithuwold on the throne of Surrey.

[42] It may be that the political basis for Mercian episcopal control of the Lindesfara was laid early in Wulfhere's reign, under Trumhere and Jaruman, the two bishops who preceded Chad.

Bede does not report the fighting, nor is it mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, but according to Stephen, Ecgfrith defeated Wulfhere, forcing him to surrender Lindsey, and to pay tribute.

[62] Wulfhere survived the defeat but evidently lost some degree of control over the south as a result; in 675, Æscwine, one of the kings of the West Saxons, fought him at Biedanheafde.

Henry of Huntingdon, a 12th-century historian who had access to versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle now lost,[63] believed that Mercians had been the victors in a "terrible battle" and remarks upon Wulfhere having inherited "the valour of his father and grandfather".

Æthelred recovered Lindsey from the Northumbrians a few years after his accession, but he was generally unable to maintain the domination of the south achieved by Wulfhere.