Xu (state)

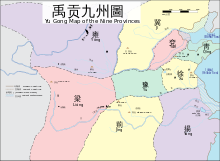

Able to consolidate its rule over a territory that stretched from Hubei in the south, through eastern Henan, northern Anhui and Jiangsu, as far north as southern Shandong,[6] Xu's confederation remained a major power until the early Spring and Autumn period.

[14] No contemporary evidence exists to verify this information and the oldest literary sources available, the oracle bones of the Shang dynasty, do not mention such an empire.

[15] Oracle bones and later historical records both indicate that the Xuzhou area was occupied by the indigenous Dapeng kingdom since the middle Shang dynasty.

[14][19] Like the Dongyi states at Pugu and Yan, Xu participated in the Rebellion of the Three Guards against the Duke of Zhou, although it had no known direct relation to the three competing parties.

[20] In contrast to other sources, the Records of the Grand Historian suggest that Xu and the Huaiyi were not involved in the initial rebellion at all, and only clashed with Zhou forces later.

[24] Despite that, Xu remained somewhat defiant, and moved its core area further south into northern Anhui in order to escape the constant pressure from the Zhou dynasty in the north.

[26] Based on archaeological findings, Edward L. Shaughnessy even speculates that the Zhou dynasty was so weakened that it largely retreated to its capital area, leaving most of its empire to fend for itself.

[27] Building upon this theory, historian Manfred Frühauf believes that the Huaiyi, among them Xu, regained their independence as consequence of this general Zhou retreat.

[29] By 944 BC, Lord Yan of Xu managed to unite thirty-six Dongyi and Huaiyi states under his leadership, declared himself king and proceeded to invade the Zhou empire.

The military contest between the Huaiyi and Zhou kingdom never really stopped, and even though the latter increasingly suffered from internal disorder and even chaos, it remained a formidable adversary for Xu's confederation.

In turn, the Huaiyi confederation under Xu began a massive counter offensive in 850 BC, aiming to conquer the North China Plain and to destroy the Zhou rule over the East.

Enlisting the military aid of several loyalist states of Shandong, he launched a massive campaign against the Xu-led Huaiyi coalition in 822 BC, eventually claiming to have won a great victory.

[42] Despite Xuan's restoration attempts, the Zhou dynasty's royal power largely collapsed in 771 BC, ushering into the Spring and Autumn period.

Xu bronzes from the early Spring and Autumn period were found in southern Jiangsu and northern Zhejiang, indicating the state's influence in or possibly even control over these regions.

Their successor, Duke Zhuang of Lu, on the other side, considered the remaining Xu tribes of Shandong a threat and started a war to eliminate them.

By that time, the only remaining northern Xu enclave of any significance was centered at Caozhou, holding the local marshes from where the Chi River originated.

In response to this aggressive expansion into its heartland, the Xu kingdom began to cooperate with Chu's northern enemies, and occupied one of the now-hostile Shu states in 656 BC.

[60] After 622 BC, Chu forced the remaining states along the middle Huai River into vassalage, destroying any of them that continued open resistance.

In that year, King Ling of Chu called for meeting of the states at the former capital of Shen, wanting them to accept him as new hegemon of China.

[66] In winter 530 BC, King Ling of Chu led another army to besiege and conquer Xu's capital in order to prepare an invasion of Wu.

Contemporary writer Zuo Qiuming believed that this hinted at the small states' increasing weakness, as they no longer had a leader among them capable of resisting invaders who were "devoid of principle".

[74] Aided by the famous military strategist Sun Tzu,[76] Helü ordered his troops to raise "embankments on the hills so as to lay the [kingdom's] capital under water".

Although Chu sent an army to relieve Xu, the situation in the besieged city became unbearable, so that Zhangyu went forth with his wife to personally surrender to King Helü.

[74] Despite its end, Xu continued to "exert a major influence in the region",[78] especially since exiles from the fallen state settled in a large area.

[79][43] Those found at Wu sites and dated to the time after Xu's destruction were probably war booty, trading goods or "tokens of political or marriage alliance".

Nevertheless, several sinologists, such as Donald B. Wagner, Constance A. Cook, and Barry B. Blakeley consider it likely that the Huaiyi were a specific people, distinct from other groups such as the Dongyi of Shandong and the Nanyi of the middle Yangtze.

[81][82][d] Archaeological excavations seem to corroborate this assumption, as they indicate that the Xu peoples had a distinct indigenous culture which had evolved from local Neolithic origins.

In fact, the Huaiyi appeared as users of bronze and copper who produced metal weapons, vessels and bells since they were first attested by Zhou sources in the eleventh century BC.

[78][43] The capital of Xu was located in Sihong County,[29] while modern-day Pizhou served as its main ritual center and necropolis for its rulers.

[90] Xu is represented with the star Theta Serpentis in asterism Left Wall, Heavenly Market enclosure (see Chinese constellation).