Year 2000 problem

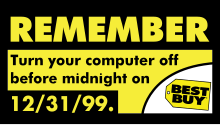

In the years leading up to the turn of the millennium, the public gradually became aware of the "Y2K scare", and individual companies predicted the global damage caused by the bug would require anything between $400 million and $600 billion to rectify.

[1] A lack of clarity regarding the potential dangers of the bug led some to stock up on food, water, and firearms, purchase backup generators, and withdraw large sums of money in anticipation of a computer-induced apocalypse.

[3][4] Then-U.S. president Bill Clinton, who organized efforts to minimize the damage in the United States, labelled Y2K as "the first challenge of the 21st century successfully met",[5] and retrospectives on the event typically commend the programmers who worked to avert the anticipated disaster.

Computerworld's 1993 three-page "Doomsday 2000" article by Peter de Jager was called "the information-age equivalent of the midnight ride of Paul Revere" by The New York Times.

As space on disc and tape storage was also expensive, these strategies saved money by reducing the size of stored data files and databases in exchange for becoming unusable past the year 2000.

While some commentators and experts argued that the coverage of the problem largely amounted to scaremongering,[17] it was only the safe passing of the main event itself, 1 January 2000, that fully quelled public fears.

[17] In a similar vein, the Microsoft Press book Running Office 2000 Professional, published in May 1999, accurately predicted that most personal computer hardware and software would be unaffected by the year 2000 problem.

We used to spend a lot of time running through various mathematical exercises before we started to write our programs so that they could be very clearly delimited with respect to space and the use of capacity.

Business data processing was done using unit record equipment and punched cards, most commonly the 80-column variety employed by IBM, which dominated the industry.

He spent the next twenty years fruitlessly trying to raise awareness of the problem with programmers, IBM, the government of the United States and the International Organization for Standardization.

[23] Despite magazine articles on the subject from 1970 onward, the majority of programmers and managers only started recognizing Y2K as a looming problem in the mid-1990s, but even then, inertia and complacency caused it to be mostly unresolved until the last few years of the decade.

Windows Mobile is the first software reported to have been affected by this glitch; in some cases WM6 changes the date of any incoming SMS message sent after 1 January 2010 from the year 2010 to 2016.

[40] The most important occurrences of such a glitch were in Germany, where up to 20 million bank cards became unusable, and with Citibank Belgium, whose Digipass customer identification chips failed.

If these systems are not updated and fixed, then dates all across the world that rely on Unix time will wrongfully display the year as 1901 beginning at 03:14:08 UTC on 19 January 2038.

As a result, a new wave of problems started appearing in 2020, including parking meters in New York City refusing to accept credit cards, issues with Novitus point of sale units, and some utility companies printing bills listing the year 1920.

[citation needed] Romania also changed its national identification number in response to the Y2K problem, due to the birth year being represented by only two digits.

"[111] In 1998, the United States government responded to the Y2K threat by passing the Year 2000 Information and Readiness Disclosure Act, by working with private sector counterparts in order to ensure readiness, and by creating internal continuity of operations plans in the event of problems and set limits to certain potential liabilities of companies with respect to disclosures about their year 2000 programs.

It was a liaison operation designed to mitigate the possibility of false positive readings in each nation's nuclear attack early warning systems.

IY2KCC's mission was to "promote increased strategic cooperation and action among governments, peoples, and the private sector to minimize adverse Y2K effects on the global society and economy."

While a range of authors responded to this wave of concern, two of the most survival-focused texts to emerge were Boston on Y2K (1998) by Kenneth W. Royce and Mike Oehler's The Hippy Survival Guide to Y2K.

[128] Adherents in these movements were encouraged to engage in food hoarding, take lessons in self-sufficiency, and the more extreme elements planned for a total collapse of modern society.

The Chicago Tribune reported that some large fundamentalist churches, motivated by Y2K, were the sites for flea market-like sales of paraphernalia designed to help people survive a social order crisis ranging from gold coins to wood-burning stoves.

[129] Betsy Hart wrote in the Deseret News that many of the more extreme evangelicals used Y2K to promote a political agenda in which the downfall of the government was a desired outcome in order to usher in Christ's reign.

[130] Y2K fears were described dramatically by New Zealand-based Christian prophetic author and preacher Barry Smith in his publication "I Spy with my Little Eye," where he dedicated an entire chapter to Y2K.

The Baltimore Sun claimed this in their article "Apocalypse Now – Y2K spurs fears," noting the increased call for repentance in the populace in order to avoid God's wrath.

"[127] However, Pat Robertson, founder of the global Christian Broadcasting Network, gave equal time to pessimists and optimists alike and granted that people should at least expect "serious disruptions".

Those who hold this view claim that the lack of problems at the date change reflects the completeness of the project, and that many computer applications would not have continued to function into the 21st century without correction or remediation.

It has been suggested that on 11 September 2001, infrastructure in New York City (including subways, phone service, and financial transactions) was able to continue operation because of the redundant networks established in the event of Y2K bug impact[141] and the contingency plans devised by companies.

[143] Backup systems were activated at various locations around the region, many of which had been established to deal with a possible complete failure of networks in Manhattan's Financial District on 31 December 1999.

[150] The 2024 CrowdStrike incident, a global IT system outage, was compared to the Y2K bug by several news outlets, recalling fears surrounding it due to its scale and impact.