Yang–Mills theory

All known fundamental interactions can be described in terms of gauge theories, but working this out took decades.

[2] Hermann Weyl's pioneering work on this project started in 1915 when his colleague Emmy Noether proved that every conserved physical quantity has a matching symmetry, and culminated in 1928 when he published his book applying the geometrical theory of symmetry (group theory) to quantum mechanics.

Erwin Schrödinger in 1922, three years before working on his equation, connected Weyl's group concept to electron charge.

He settled on conservation of isospin, a quantum number that distinguishes a neutron from a proton, but he made no progress on a theory.

[3]: 200 Taking a break from Princeton in the summer of 1953, Yang met a collaborator who could help: Robert Mills.

As Mills himself describes:"During the academic year 1953–1954, Yang was a visitor to Brookhaven National Laboratory ...

Yang, who has demonstrated on a number of occasions his generosity to physicists beginning their careers, told me about his idea of generalizing gauge invariance and we discussed it at some length ...

I was able to contribute something to the discussions, especially with regard to the quantization procedures, and to a small degree in working out the formalism; however, the key ideas were Yang's.

Yang's presentation of the work at Princeton in February 1954 was challenged by Pauli, asking about the mass in the field developed with the gauge invariance idea.

[3]: 202 Pauli knew that this might be an issue as he had worked on applying gauge invariance but chose not to publish it, viewing the massless excitations of the theory to be "unphysical 'shadow particles'".

[2]: 13 Yang and Mills published in October 1954; near the end of the paper, they admit: We next come to the question of the mass of the

[3] The idea was set aside until 1960, when the concept of particles acquiring mass through symmetry breaking in massless theories was put forward, initially by Jeffrey Goldstone, Yoichiro Nambu, and Giovanni Jona-Lasinio.

This prompted a significant restart of Yang–Mills theory studies that proved successful in the formulation of both electroweak unification and quantum chromodynamics (QCD).

The dynamics of the photon field and its interactions with matter are, in turn, governed by the U(1) gauge theory of quantum electrodynamics.

Phenomenology at lower energies in quantum chromodynamics is not completely understood due to the difficulties of managing such a theory with a strong coupling.

In 1953, in a private correspondence, Wolfgang Pauli formulated a six-dimensional theory of Einstein's field equations of general relativity, extending the five-dimensional theory of Kaluza, Klein, Fock, and others to a higher-dimensional internal space.

Because Pauli found that his theory "leads to some rather unphysical shadow particles", he refrained from publishing his results formally.

[6] Although Pauli did not publish his six-dimensional theory, he gave two seminar lectures about it in Zürich in November 1953.

[6] In January 1954 Ronald Shaw, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge also developed a non-Abelian gauge theory for nuclear forces.

Since no such massless particles were known at the time, Shaw and his supervisor Abdus Salam chose not to publish their work.

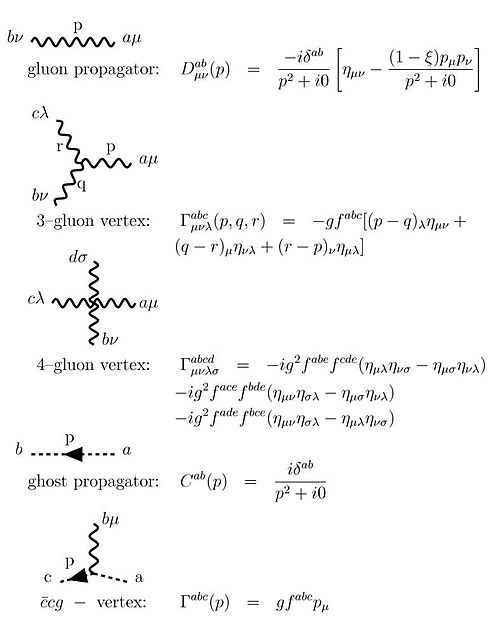

[citation needed] Note that the transition between "upper" ("contravariant") and "lower" ("covariant") vector or tensor components is trivial for a indices (e.g.

enters into the equations of motion as Note that the currents must properly change under gauge group transformations.

This problem was already known for quantum electrodynamics but here becomes more severe due to non-abelian properties of the gauge group.

Using LSZ reduction formula we get from the n-point functions the corresponding process amplitudes, cross sections and decay rates.

In this case, large computational resources are needed to be sure the correct limit of infinite volume (smaller lattice spacing) is obtained.

As of today, the situation appears somewhat satisfactory for the hadronic spectrum and the computation of the gluon and ghost propagators, but the glueball and hybrids spectra are yet a questioned matter in view of the experimental observation of such exotic states.

The mathematics of the Yang–Mills theory is a very active field of research, yielding e.g. invariants of differentiable structures on four-dimensional manifolds via work of Simon Donaldson.

Furthermore, the field of Yang–Mills theories was included in the Clay Mathematics Institute's list of "Millennium Prize Problems".

Here the prize-problem consists, especially, in a proof of the conjecture that the lowest excitations of a pure Yang–Mills theory (i.e. without matter fields) have a finite mass-gap with regard to the vacuum state.

Another open problem, connected with this conjecture, is a proof of the confinement property in the presence of additional fermions.