Yusuf and Zulaikha

According to Agnès Kefeli, "in the biblical and Qur’anic interpretations of Joseph's story, Potiphar's wife bears all the blame for sin and disappears quickly from the narrative".

But "in Turkic and Persian literatures (although not in the Qur’an or the Arabic tales of the prophets), Joseph and Zulaykha do, ultimately, become sexually united, in parallel to their noncorporeal mystical union".

[1]: 384 The story of Yusuf and Zulaikha is subsequently found in many languages, such as Arabic, Persian, Bengali, Turkish, Punjabi and Urdu.

Though found widely in the Muslim world, the story of Yusuf and Zulaika seems first to have achieved a developed an independent form in Persian literature around the tenth century CE: there is evidence for a lost narrative poem on the subject by the tenth-century Abu l-Muʾayyad Balkhī (as well as one by an otherwise unknown Bakhtiyārī of apparently similar date).

After reaching maturity, Yusuf becomes so beautiful that his master's wife, later called Zulaikha in the Islamic tradition, falls in love with him.

[17] The first surviving Persian narrative account of Yusuf and Zulaikha is a probably eleventh-century mathnawī called Yūsuf u Zulaykhā.

From as early as the fifteenth century into the twentieth, this account was thought to be by the renowned poet Firdawsī, composer of the secular Persian epic Shahnameh, but the authorship is now regarded as unknown.

[18][19][20] While Yūsuf u Zulaykhā does not seem to have been particularly influential on Persian tradition, it was a key source for the account of Yusuf in Shāhīn-i Shīrāzī's Judaeo-Persian Bereshit-nāma, a mathnawī on the Book of Genesis composed around 1358.

[2] In 1483 AD, the renowned poet Jami wrote his interpretation of the allegorical romance and religious texts of Yusuf and Zulaikha.

Jami's example shows how a religious community takes a story from a sacred text and appropriate it in a religious-socio-cultural setting that is different from the original version.

A prime example of syncretism, it blends elements of Hindu culture with the classic Islamic tale, which in turn encourages readers to coexist with other faiths.

It is known for its detailed descriptions of Yusuf and Zulaikha's physical beauty, and begins with the two protagonists' childhoods, which then unravels into a tale full of passion and pursuit.

[32] Following the introduction of Sagir's poem, other Bengali writers throughout the centuries took inspiration and created their own versions of Yusuf and Zulaikha, including Abdul Hakim and Shah Garibullah.

[33] There also exists a Punjabi Qisse version of Yusuf and Zulaikha, composed by Hafiz Barkhurdar, that contains around 1200 pairs of rhyming verses.

This is evident in Maulvi Abd al-Hakim's interpretation of Yusuf and Zulaikha, which directly imitates Jami as well as other features of the Persian language.

Based on Jami's Persian version, Munshi Sadeq Ali also wrote this story as a poetic-style puthi in the Sylheti Nagari script, which he titled Mahabbatnama.

[41] In 1492 CE, an Ottoman Turkish mathnawī of Yusuf and Zulaikha, mixing poetry in the khafīf metre with ghazal was completed by Ḥamd Allāh Ḥamdī.

Substantial periods of conquest and dissolution of Islam throughout Asia and North Africa led to a flurry of diverse artistic interpretations of Yusuf and Zulaikha.

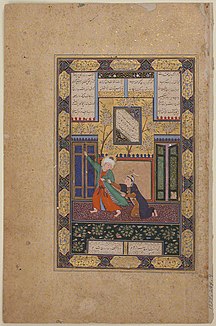

Within one of the wealthiest trading centers along the Silk Road in Bukhara, Uzbekistan, the manuscript of Bustan of Sa’di would be found.

From such an economic boom the Bustan of Sa’di created in 1257 C.E portrays many scenes from the poems of Yusuf and Zulaikha.

The scene demonstrated visually a prominent theme from the poem in which we see Yusuf's powerful faith in God overcome his own physical desires.

As depicted in the artwork, the locked doors unexpectedly spring open, offering Yusuf a path from Zulaikha's home.

In crafting this piece the materials used fall in line with the conventional methods used at the time and were a mixture of oil paints, gold and watercolors.

The artist Kamāl al-Dīn Behzād under the direction of Sultan Husayn Bayqara of the Timurid Empire) constructed a manuscript illustrating the tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha.

His artistic style of blending the traditional geometric shape with open spaces to create a central view of his characters was a new idea evident in many of his works.

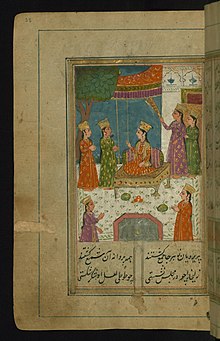

In a work originating from the Kashmir region of India, we see how under the Islamic Mughal Empire the renowned poem of Yusuf and Zulaikha continued to flourish in art.

[50] The continued interest in illustrating the renowned tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha can be found in a manuscript from Muhhamid Murak dating back to the year 1776.