Babur

Babur formed a partnership with the Safavid emperor Ismail I and reconquered parts of Turkestan, including Samarkand, only to again lose it and the other newly conquered lands to the Shaybanids.

Nonetheless, Sanga suffered a major defeat due to Babur's skillful troop positioning and use of gunpowder, specifically matchlocks and small cannons.

[20] The difficulty of pronouncing the name for his Central Asian Turco-Mongol army may have been responsible for the greater popularity of his nickname Babur,[21] also variously spelled Baber,[22] Babar,[23] and Bābor.

They are known as the Baburnama and were written in Chagatai, his first language,[27] though, according to Dale, "his Turkic prose is highly Persianized in its sentence structure, morphology or word formation and vocabulary.

[29] Babur hailed from the Turkic Barlas tribe, which was of Mongol origin and had embraced the Turco-Persian tradition[30][31] They had also converted to Islam centuries earlier and resided in Turkestan and Khorasan.

[33] Hence, Babur, though nominally a Mongol (or Moghul in Persian language), drew much of his support from the local Turkic and Iranian people of Central Asia, and his army was diverse in its ethnic makeup.

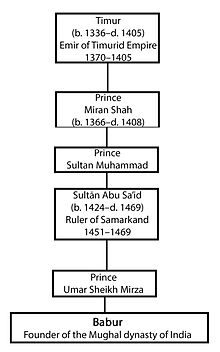

[34] In 1494, eleven-year-old Babur became the ruler of Fergana, in present-day Uzbekistan, after Umar Sheikh Mirza died "while tending pigeons in an ill-constructed dovecote that toppled into the ravine below the palace".

[35] During this time, two of his uncles from the neighbouring kingdoms, who were hostile to his father, and a group of nobles who wanted his younger brother Jahangir to be the ruler, threatened his succession to the throne.

[21] Babur was able to hold the city despite desertions in his army, but he later fell seriously ill.[37] Meanwhile, a rebellion back home, approximately 350 kilometres (220 mi) away, amongst nobles who favoured his brother, robbed him of Fergana.

He then tried to reclaim Fergana, but lost the battle there also and, escaping with a small band of followers, he wandered the mountains of central Asia and took refuge with hill tribes.

[41] In the same year, Babur united with Sultan Husayn Mirza Bayqarah of Herat, a fellow Timurid and distant relative, against their common enemy, the Uzbek Shaybani.

[43] Babur became the only reigning ruler of the Timurid dynasty after the loss of Herat, and many princes sought refuge with him at Kabul because of Shaybani's invasion in the west.

[49] Determined to conquer the Uzbeks and recapture his ancestral homeland, Babur was wary of their allies the Ottomans, and made no attempt to establish formal diplomatic relations with them.

"[49] After his third loss of Samarkand, Babur gave full attention to the conquest of North India, launching a campaign; he reached the Chenab River, now in Pakistan, in 1519.

In response, Babur burned Lahore for two days, then marched to Dibalpur, placing Alam Khan, another rebel uncle of Lodi, as governor.

[40][51] In the battle that began on the following day, Babur used the tactic of Tulugma, encircling Ibrahim Lodi's army and forcing it to face artillery fire directly, as well as frightening its war elephants.

[40] Babur wrote in his memoirs about his victory: By the grace of the Almighty God, this difficult task was made easy to me and that mighty army, in the space of a half a day was laid in dust.

[40]After the battle, Babur occupied Delhi and Agra, took the throne of Lodi, and laid the foundation for the eventual rise of Mughal rule in India.

Rana Sanga wanted to overthrow Babur, whom he considered to be a foreigner ruling in India, and also to extend the Rajput territories by annexing Delhi and Agra.

Upon receiving news of Rana Sangha's advance towards Agra, Babur took a defensive position at Khanwa (currently in the Indian state of Rajasthan), from where he hoped to launch a counterattack later.

Rao also notes that Rana Sanga faced "treachery" when the Hindu chief Silhadi joined Babur's army with a garrison of 6,000 soldiers.

[citation needed] Historians suggest the early Mughal period of religious violence contributed to introspection and then the transformation in Sikhism from pacifism to militancy for self-defense.

[62] According to Babur's autobiography, Baburnama, his campaign in northwest India targeted Hindus and Sikhs as well as apostates (non-Sunni sects of Islam), and an immense number were killed, with Muslim camps building "towers of skulls of the infidels" on hillocks.

Babur was opposed to the blind obedience towards the Chinggisid laws and customs that were influential in Turco-Mongol society:"Previously our ancestors had shown unusual respect for the Chingizid code (törah).

He authored his famous memoir the Bāburnāma, as well as beautiful lyrical works or ghazals, treatises on Muslim jurisprudence (Mubayyin), poetics (Aruz risolasi), music, and a special calligraphy, known as khatt-i Baburi.

[73] The following ruba'i is an example of Babur's poetry written in Turkic, composed in the aftermath of his famous victory in North India to celebrate his ghazi status.

[94] Quoting Henry Beveridge, Stanley Lane-Poole writes: His autobiography is one of those priceless records which are for all time, and is fit to rank with the confessions of St. Augustine and Rousseau, and the memoirs of Gibbon and Newton.

In 2003 the Allahabad High Court ordered the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) to conduct a more in-depth study and an excavation to ascertain the type of structure beneath the mosque.

[101] Archaeologist KK Muhammed, the only Muslim member in the team of people surveying the excavation, also confirmed individually that there existed a temple like structure before the Babri Masjid was constructed over it.

[103] According to archaeologist Supriya Verma and Jaya Menon, who observed the excavations on behalf of the Sunni Waqf Board, "the ASI was operating with a preconceived notion of discovering the remains of a temple beneath the demolished mosque, even selectively altering the evidence to suit its hypothesis."