Zoroaster

[15] Zoroaster is credited with authorship of the Gathas as well as the Yasna Haptanghaiti, a series of hymns composed in Old Avestan that cover the core of Zoroastrian thinking.

His translated name, "Zoroaster", derives from a later (5th century BC) Greek transcription, Zōroastrēs (Ζωροάστρης),[17] as used in Xanthus's Lydiaca (Fragment 32) and in Plato's First Alcibiades (122a1).

[27] Some scholars propose that the chronological calculation for Zoroaster was developed by Persian magi in the 4th century BC, and as the early Greeks learned about him from the Achaemenids, this indicates they did not regard him as a contemporary of Cyrus the Great, but as a remote figure.

[14][6] The basis of this theory is primarily proposed on linguistic similarities between the Old Avestan language of the Zoroastrian Gathas and the Sanskrit of the Rigveda (c. 1700–1100 BC), a collection of early Vedic hymns.

[52] Yasna 9 and 17 cite the Ditya River in Airyanem Vaējah (Middle Persian Ērān Wēj) as Zoroaster's home and the scene of his first appearance.

[55] On the other hand, in post-Islamic sources Shahrastani (1086–1153), an Iranian writer originally from Shahristān, in present-day Turkmenistan, proposed that Zoroaster's father was from Atropatene (also in Medea) and his mother was from Rey.

[65] By the age of 30, Zoroaster experienced a revelation during a spring festival; on the river bank he saw a shining being, who revealed himself as Vohu Manah (Good Purpose) and taught him about Ahura Mazda (Wise Lord) and five other radiant figures.

[67] Eventually, at the age of about 42, Zoroaster received the patronage of queen Hutaosa and a ruler named Vishtaspa, an early adherent of Zoroastrianism (possibly from Bactria according to the Shahnameh).

The Dēnkart, and the epic Shahnameh, ascribe his death to a Turanian soldier named Baraturish, potentially a spin on the same figure, while other traditions combine both accounts or hold that he died of old age.

[74] The French figurist Jesuit missionary to China Joachim Bouvet thought that Zoroaster, the Chinese cultural hero Fuxi and Hermes Trismegistus were actually the Biblical patriarch Enoch.

Such parallels include the evident similarities between Amesha Spenta and the archangel Gabriel, praying five times a day, covering one's head during prayer, and the mention of Thamud and Iram of the Pillars in the Quran.

[78] Like the Greeks of classical antiquity, Islamic tradition understands Zoroaster to be the founding prophet of the Magians (via Aramaic, Arabic Majūsiyya, collective Majūs).

The 11th-century Cordoban Ibn Hazm (Zahiri school) contends that the designation kitābī "[follower] of the Scripture [of God]" cannot apply in light of the Zoroastrian assertion that their books were destroyed by Alexander.

Citing the authority of the 8th-century al-Kalbi, the 9th- and 10th-century Sunni historian al-Tabari (I, 648)[citation needed] reports that Zaradusht bin Isfiman (an Arabic adaptation of "Zarathushtra Spitama") was an inhabitant of Israel and a servant of one of the disciples of the prophet Jeremiah.

Upon their arrival, Zaradusht translated the sage's Hebrew teachings for the king and so convinced him to convert (Tabari also notes that they had previously been Sabis) to the Magian religion.

[86] Zoroaster's ethical dualism is—to an extent—incorporated in Manichaeism's doctrine which, unlike Mani's thoughts,[87] viewed the world as being locked in an epic battle between opposing forces of good and evil.

The encyclopedia Natural History (Pliny) claims that Zoroastrians later educated the Greeks who, starting with Pythagoras, used a similar term, philosophy, or "love of wisdom" to describe the search for ultimate truth.

Thus, mankind are not the slaves or servants of Ahura Mazda, but can make a personal choice to be co-workers, thereby perfecting the world as saoshyants ("world-perfecters") and eventually achieving the status of an Ashavan ("master of Asha").

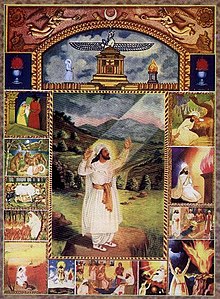

[citation needed] Although a few recent depictions of Zoroaster show him performing some deed of legend, in general the portrayals merely present him in white vestments (which are also worn by present-day Zoroastrian priests).

The Greeks—in the Hellenistic sense of the term—had an understanding of Zoroaster as expressed by Plutarch, Diogenes Laertius, and Agathias[100] that saw him, at the core, to be the "prophet and founder of the religion of the Iranian peoples," Beck notes that "the rest was mostly fantasy".

[110] Association with astrology according to Roger Beck, were based on his Babylonian origin, and Zoroaster's Greek name was identified at first with star-worshiping (astrothytes, 'star sacrificer") and, with the Zo-, even as the 'living' star.

Pliny's 2nd- or 3rd-century attribution of "two million lines" to Zoroaster suggest that (even if exaggeration and duplicates are taken into consideration) a formidable pseudepigraphic corpus once existed at the Library of Alexandria.

[117] The exception to the fragmentary evidence (i.e. reiteration of passages in works of other authors) is a complete Coptic tractate titled Zostrianos (after the first-person narrator) discovered in the Nag Hammadi library in 1945.

"[105] A third text attributed to Zoroaster is On Virtue of Stones (Peri lithon timion), of which nothing is known other than its extent (one volume) and that pseudo-Zoroaster 'sang' it (from which Cumont and Bidez[who?]

[119] This notion of Zoroaster's laughter also appears in the 9th– to 11th-century texts of genuine Zoroastrian tradition, and for a time it was assumed[weasel words] that the origin of those myths lay with indigenous sources.

[citation needed] Pliny also records that Zoroaster's head had pulsated so strongly that it repelled the hand when laid upon it, a presage of his future wisdom.

[citation needed] For instance, Plutarch's description of its dualistic theologies reads thus: "Others call the better of these a god and his rival a daemon, as, for example, Zoroaster the Magus, who lived, so they record, five thousand years before the siege of Troy.

A sculpture of Zoroaster by Edward Clark Potter, representing ancient Persian judicial wisdom and dating to 1896, towers over the Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State at East 25th Street and Madison Avenue in Manhattan.

[128][129][130] A sculpture of Zoroaster is included among other prominent religious figures in a procession representing major faith traditions on the south side of Rockefeller Memorial Chapel at the University of Chicago.

It features figures from Abraham to the Reformation, illustrating a historical continuum of religious thought that includes the likes of Zoroaster, Moses, Plato and others.