Mithraism

[8][full citation needed] No written narratives or theology from the religion survive; limited information can be derived from the inscriptions and brief or passing references in Greek and Latin literature.

[i] An early example of the Greek form of the name is in a 4th century BCE work by Xenophon, the Cyropaedia, which is a biography of the Persian king Cyrus the Great.

The centre-piece is Mithras clothed in Anatolian costume and wearing a Phrygian cap; who is kneeling on the exhausted bull, holding it by the nostrils[4](p 77) with his left hand, and stabbing it with his right.

[28] Besides the main cult icon, a number of mithraea had several secondary tauroctonies, and some small portable versions, probably meant for private devotion, have also been found.

[30](pp 286–287) On the specific banquet scene on the Fiano Romano relief, one of the torchbearers points a caduceus towards the base of an altar, where flames appear to spring up.

An example of such a catechism, apparently pertaining to the Leo grade, was discovered in a fragmentary Egyptian papyrus (Papyrus Berolinensis 21196),[45][47] and reads: Almost no Mithraic scripture or first-hand account of its highly secret rituals survives;[o] with the exception of the aforementioned oath and catechism, and the document known as the Mithras Liturgy, from 4th century Egypt, whose status as a Mithraist text has been questioned by scholars including Franz Cumont.

Beck argues that religious celebrations on this date are indicative of special significance being given to the summer solstice; but this time of the year coincides with ancient recognition of the solar maximum at midsummer, when iconographically identical holidays such as Litha, Saint John's Eve, and Jāņi are also observed.

Burned residues of animal entrails are commonly found on the main altars, indicating regular sacrificial use, though mithraea do not commonly appear to have been provided with facilities for ritual slaughter of sacrificial animals (a highly specialised function in Roman religion), and it may be presumed that a mithraeum would have made arrangements for this service to be provided for them in co-operation with the professional victimarius[51](p 568) of the civic cult.

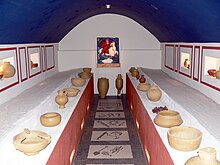

[z] For the most part, mithraea tend to be small, externally undistinguished, and cheaply constructed; the cult generally preferring to create a new centre rather than expand an existing one.

The term is used in an inscription by Proficentius[b] and derided by Firmicus Maternus in De errore profanarum religionum,[61] a 4th century Christian work attacking paganism.

[63] Activities of the most prominent deities in Mithraic scenes, Sol and Mithras, were imitated in rituals by the two most senior officers in the cult's hierarchy, the Pater and the Heliodromus.

A noticeable feature of this narrative (and of its regular depiction in surviving sets of relief carvings) is the absence of female personages (the sole exception being Luna watching the tauroctony in the upper corner opposite Helios, and the presumable presence of Venus as patroness of the nymphus grade).

[2] According to Geden, while the participation of women in the ritual was not unknown in the Eastern cults, the predominant military influence in Mithraism makes it unlikely in this instance.

[4](p 39) Clauss suggests that a statement by Porphyry, that people initiated into the Lion grade must keep their hands pure from everything that brings pain and harm and is impure, means that moral demands were made upon members of congregations.

[79](p 118) Inscriptions and monuments related to the Mithraic Mysteries are catalogued in a two volume work by Maarten J. Vermaseren, the Corpus Inscriptionum et Monumentorum Religionis Mithriacae (or CIMRM).

[90] The historian Dio Cassius (2nd to 3rd century CE) tells how the name of Mithras was spoken during the state visit to Rome of Tiridates I of Armenia, during the reign of Nero.

[93] Citing Eubulus as his source, Porphyry writes that the original temple of Mithras was a natural cave, containing fountains, which Zoroaster found in the mountains of Persia.

Franz Cumont argued that it isn't;[101](p 12) Marvin Meyer thinks it is;[98](pp 180–182) while Hans Dieter Betz sees it as a synthesis of Greek, Egyptian, and Mithraic traditions.

[111] A similar view has been expressed by Luther H. Martin: "Apart from the name of the god himself, in other words, Mithraism seems to have developed largely in and is, therefore, best understood from the context of Roman culture.

"[17] Reporting on the Second International Congress of Mithraic Studies, 1975, Ugo Bianchi says that although he welcomes "the tendency to question in historical terms the relations between Eastern and Western Mithraism", it "should not mean obliterating what was clear to the Romans themselves, that Mithras was a 'Persian' (in wider perspective: an Indo-Iranian) god.

"[113] Boyce wrote, "no satisfactory evidence has yet been adduced to show that, before Zoroaster, the concept of a supreme god existed among the Iranians, or that among them Mithra – or any other divinity – ever enjoyed a separate cult of his or her own outside either their ancient or their Zoroastrian pantheons.

[ay] He says that ... an indubitable residuum of things Persian in the Mysteries and a better knowledge of what constituted actual Mazdaism have allowed modern scholars to postulate for Roman Mithraism a continuing Iranian theology.

More problematic – and never properly addressed by Cumont or his successors – is how real-life Roman Mithraists subsequently maintained a quite complex and sophisticated Iranian theology behind an occidental facade.

"[118] Beck theorizes that the cult was created in Rome, by a single founder who had some knowledge of both Greek and Oriental religion, but suggests that some of the ideas used may have passed through the Hellenistic kingdoms.

[9](pp 77 ff) A. D. H. Bivar, L. A. Campbell, and G. Widengren have variously argued that Roman Mithraism represents a continuation of some form of Iranian Mithra worship.

[bb] Mithraism reached the apogee of its popularity during the 2nd and 3rd centuries, spreading at an "astonishing" rate at the same period when the worship of Sol Invictus was incorporated into the state-sponsored cults.

In particular, large numbers of votive coins deposited by worshippers have been recovered at the Mithraeum at Pons Sarravi (Sarrebourg) in Gallia Belgica, in a series that runs from Gallienus (r. 253–268) to Theodosius I (r. 379–395).

[143] Jelbert argues that within the tauroctony image, Mithras' body is analogous to the path of the Milky Way that bridges Taurus and Scorpius, and that this bifurcated section mirrors the shape, scale and position of the deity relative to the other characters in the scene.

[149] Justin Martyr contrasted Mithraic initiation communion with the Eucharist:[150] Ernest Renan suggested in 1882 that, under different circumstances, Mithraism might have risen to the prominence of modern-day Christianity.

[br] David Ulansey thinks Renan's statement "somewhat exaggerated",[bs] but does consider Mithraism "one of Christianity's major competitors in the Roman Empire".