Zeebrugge Raid

The port was used by the Imperial German Navy as a base for U-boats and light shipping, which were a threat to Allied control of the English Channel and southern North Sea.

Several attempts to close the Flanders ports by bombardment failed and Operation Hush, a 1917 plan to advance up the coast, proved abortive.

Two of three blockships were scuttled in the narrowest part of the Bruges–Ostend Canal and one of two submarines rammed the viaduct linking the shore and the mole, to trap the German garrison.

At the end of 1916 a combined operation against Borkum, Ostend and Zeebrugge had been considered by Admiral Sir Lewis Bayly, commander of the Coast of Ireland Station.

A bombardment of the Zeebrugge lock gates under cover of a smoke screen was studied by Vice-Admiral Sir Reginald Bacon, commander of the Dover Patrol and the Admiralty in late 1915 but was also rejected as too risky.

The raid was proposed in 1917 by Admiral Sir John Jellicoe but was not authorised until Keyes adapted Bacon's plan for a blocking operation, to make it difficult for German ships and submarines to leave the port.

Mist and low cloud would make artillery observation from an aircraft impossible and the wind would have to be blowing from a narrow range of bearings or the smoke screen would be carried over the ships and out to sea, exposing them to view from the shore.

Firing from the monitors was opened just after 5:00 a.m. and at first fell short; many of the shells failed to explode, which left the aircraft unable to signal the fall of shot.

When the Pups from 4 (Naval) Squadron arrived, twice their number of German Albatros fighters engaged them and some of the aircraft from over the fleet, which joined in the dogfight.

The basin north of the locks had been hit and some damage caused to the docks but Zeebrugge remained open to German destroyers and U-boats.

[9] The Admiralty concluded that had the monitors been ready to fire as soon as the observer in the artillery-observation aircraft signalled or if the shoot had been reported throughout, the lock gates would have been hit.

The German destroyers frustrated two attempts to enter the harbour, which left the fleet without sighting data and reliant on dead reckoning.

The covering force guarded the ships from a point 5 nmi (5.8 mi; 9.3 km) distant, having engaged two German destroyers as they tried to reach Zeebrugge, sinking S20.

The dockyard was hit by twenty out of 115 shells and intelligence reports noted the sinking of a lighter, a UC-boat, damage to three destroyers and that the German command had been made anxious about the security of the coast.

Had Bacon been able to repeat the shore bombardments at short intervals, naval operations from the Flanders coast by the Germans would have been much more difficult to organise.

[13] As the long methodical bombardments of Ostend and Zeebrugge had proved impractical, Bacon attached a large monitor to the forces which patrolled coastal barrages, ready to exploit opportunities of favourable wind and weather to bombard Zeebrugge and Ostend, which occurred several times but had no effect on the working of the ports.

The only vulnerable part of the German defensive system was the lock gates at Zeebrugge, the destruction of which would make the canal to Bruges tidal and drastically reduce the number of ships and submarines that could pass along it.

The success of the raid depended upon smokescreens to protect the British ships from the fire of German coastal artillery but the wind direction was unfavourable and the attack was called off.

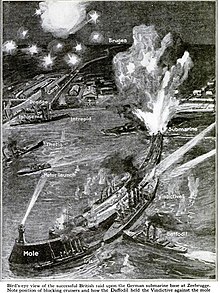

The raid began with a diversion against the mile-long Zeebrugge mole, led by the old cruiser, Vindictive, with two Mersey ferries, Daffodil and Iris II.

Vindictive was to land a force of 200 sailors and a battalion of Royal Marines, at the entrance to the Bruges–Ostend Canal, to destroy German gun positions.

Vindictive was spotted by German gunners and forced to land in the wrong place, resulting in the loss of the marines' heavy gun support.

The failure of the attack on the Zeebrugge mole resulted in the Germans concentrating their fire on the three blocking ships, HMS Thetis, Intrepid and Iphigenia, which were filled with concrete.

Thetis, which had been ordered to ram the lock gates at the end of the channel, was severely damaged by German fire and collided with a submerged wire net, which disabled both of its engines.

[31] Newbolt considered that the reduced traffic was caused by the recall of some U-boats to Germany in June, after reports that operations in the Dover Straits had become too dangerous.

[31] Newbolt wrote that the raid on Zeebrugge was part of an anti-submarine campaign which had lasted for five months, using patrols and minefields to close the Straits and which continued despite the most destructive sortie achieved by the Germans during the war.

[32] News of the raid was skilfully exploited to raise Allied morale and to foreshadow victory Possunt quia posse videntur ("They can because they think they can").

[44] A ballot was similarly held for the crews of the assault vessels for the Zeebrugge Mole (Vindictive, Royal Daffodil and Iris II) and the raiding parties.