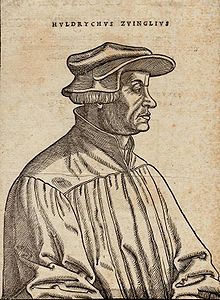

Theology of Huldrych Zwingli

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers.

He denied the Catholic doctrine of transubstantiation and following Cornelius Henrici Hoen, he agreed that the bread and wine of the institution signify and do not literally become the body and blood of Jesus Christ.

Zwingli's differences of opinion on this with Martin Luther resulted in the failure of the Marburg Colloquy to bring unity between the two Protestant leaders.

Christians were obliged to obey the government, but civil disobedience was allowed if the authorities acted against the will of God.

This is strongly evident in his early writings such as Archeteles (1522) and The Clarity and Certainty of the Word of God (1522).

[3] The inspiration of scripture, the concept that God or the Holy Spirit is the author, was taken for granted by Zwingli.

His view of inspiration was not mechanical and he recognized the human element in his commentaries as he noted the differences in the canonical gospels.

[6] Zwingli rooted his theology of salvation deeply in Augustinian soteriology[7] alongside Martin Luther (1483-1546)[8] and John Calvin (1509–1564).

In October 1523, the controversy over the issue broke out during the second Zürich disputation and Zwingli vigorously defended the need for infant baptism and his belief that rebaptism was unnecessary.

He accused the Anabaptists of adding to the word of God and noted that there is no law forbidding infant baptism.

He argued against their view that those that received the Spirit and were able to live without sin were the only persons qualified to partake in baptism.

He refers to I Corinthians 7:12–14 which states that the children of one Christian parent are holy and thus they are counted among the sons of God.

[19] Zwingli credited the Dutch humanist, Cornelius Henrici Hoen (Honius), for first suggesting the "is" in the institution words "This is my body" meant "signifies".

In The Eucharist (1525), following the introduction of his communion liturgy, he laid out the details of his theology where he argues against the view that the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ and that they are eaten bodily.

However, Zwingli also called Luther "one of the first champions of the Gospel", a David against Goliath, a Hercules who slew the Roman boar.

[24] Martin Bucer and Johannes Oecolampadius most likely influenced Zwingli as they were concerned with reconciliation of the eucharistic views.

[25] The main issue for Zwingli is that Luther puts "the chief point of salvation in the bodily eating of the body of Christ".

However, it was Zwingli's and Luther's differences in their understanding of faith, their Christology, their approach and use of scripture that ultimately made any agreement impossible.

The development of the complex relationship between church and state in Zwingli's view can only be understood by examining the context of his life, the city of Zürich, and the wider Swiss Confederation.

His earliest writings before he became a reformer, such as The Ox (1510) and The Labyrinth (1516), reveal a patriotic love of his land, a longing for liberty, and opposition to the mercenary service where young Swiss citizens were sent to fight in foreign wars for the financial benefit of the state government.

His life as a parish priest and an army chaplain helped to develop his concern for morality and justice.

Even before the Reformation, the council operated relatively independently on church matters although the areas of doctrine and worship were left to the authority of the ecclesiastical hierarchy.

As Zwingli was convinced that doctrinal matters had to conform to the word of God rather than the hierarchy, he recognised the role of the council as the only body with power to act if the religious authorities refused to undertake reform.

His theocratic views are best expressed in Divine and Human Righteousness (1523) and An Exposition of the Articles (1523) in that both preacher and prince were servants under the rule of God.