1815 eruption of Mount Tambora

The ash from the eruption column dispersed around the world and lowered global temperatures in an event sometimes known as the Year Without a Summer in 1816.

[6] This brief period of significant climate change triggered extreme weather and harvest failures in many areas around the world.

Several climate forcings coincided and interacted in a systematic manner that has not been observed after any other large volcanic eruption since the early Stone Age.

Soon after, a violent whirlwind ensued, which hit the village of Saugur (now Sangar), blowing down nearly every house and carrying everything it encountered into the air, including large trees.

[11] Pyroclastic flows cascaded down the mountain to the sea on all sides of the peninsula, wiping out the village of Tambora, and affecting a total area on land of about 874 km2 (337 sq mi).

[12][13] A moderate-sized tsunami struck the shores of various islands in the Indonesian archipelago on 10 April, with a height of up to 4 m (13 ft) in Sanggar around 22:00.

A nitrous odor was noticeable in Batavia, and heavy tephra-tinged rain fell, finally receding between 11 and 17 April.

There were still on the road side the remains of several corpses, and the marks of where many others had been interred: the villages almost entirely deserted and the houses fallen down, the surviving inhabitants having dispersed in search of food.

Since the eruption, a violent diarrhoea has prevailed in Bima, Dompo, and Sang'ir, which has carried off a great number of people.

It is supposed by the natives to have been caused by drinking water which has been impregnated with ashes; and horses have also died, in great numbers, from a similar complaint.

[8] Between 1 and 3 October the British ships Fairlie and James Sibbald encountered extensive pumice rafts about 3,600 km (2,200 mi) west of Tambora.

[20] Tanguy's revision of the death toll was based on Zollinger's work on Sumbawa for several months after the eruption and on Thomas Raffles's notes.

[4] Reid has estimated that 100,000 people on Sumbawa, Bali, and other locations died from the direct and indirect effects of the eruption.

[22] The scale of the volcanic eruption will determine the significance of the impact on climate and other chemical processes, but a change will be measured even in the most local of environments.

On 4 June 1816, frosts were reported in the upper elevations of New Hampshire, Maine (then part of Massachusetts), Vermont, and northern New York.

[4] The climate changes disrupted the Indian monsoons, caused three failed harvests and famine, and contributed to the spread of a new strain of cholera that originated in Bengal in 1816.

The crisis was severe in Germany, where food prices rose sharply, and demonstrations in front of grain markets and bakeries, followed by riots, arson, and looting, took place in many European cities.

[4] Volcanism affects the atmosphere in two distinct ways: short-term cooling caused by reflected insolation and long-term warming from increased CO2 levels.

(Williams 2012)[citation needed] Toxic gases also were pumped into the atmosphere, including sulfur that caused lung infections.

(Cole-Dai et al. 2009)[citation needed] The ejection of these gases, especially hydrogen chloride, caused the precipitation to be extremely acidic, killing much of the crops that survived or were rebudding during the spring.

[4] The ash in the atmosphere for several months after the eruption reflected significant amounts of solar radiation, causing unseasonably cool summers that contributed to food shortages.

The monsoon season in China and India was altered, causing flooding in the Yangtze Valley and forcing thousands of Chinese to flee coastal areas.

(Granados et al. 2012)[citation needed] The gases also reflected some of the already-decreased incoming solar radiation, causing a 0.4 to 0.7 °C (0.7 to 1.3 °F) decrease in global temperatures throughout the decade.

The winter of 1817, however, was radically different, with temperatures below −34 °C (−30 °F) in central and northern New York, which were cold enough to freeze lakes and rivers that were normally used to transport supplies.

Both Europe and North America suffered from freezes lasting well into June, with snow accumulating to 32 cm (13 in) in August, which killed recently planted crops and crippled the food industry.

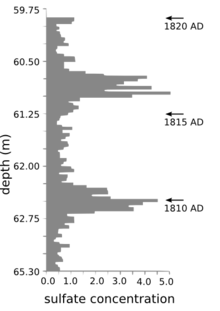

(Robock 2000)[citation needed] Scientists have used ice cores to monitor atmospheric gases during the cold decade (1810–1819), and the results have been puzzling.

The high concentrations of sulfur could have caused a four-year stratospheric warming of around 15 °C (27 °F), resulting in a delayed cooling of surface temperatures that lasted for nine years.

[4] Climate data have shown that the variance between daily lows and highs may have played a role in the lower average temperature because the fluctuations were much more subdued.

Southeastern England, northern France, and the Netherlands experienced the greatest amount of cooling in Europe, accompanied by New York, New Hampshire, Delaware, and Rhode Island in North America.

[28] The documented rainfall was as much as 80 percent more than the calculated normal with regards to 1816, with unusually high amounts of snow in Switzerland, France, Germany, and Poland.