1838 Mormon War

[2] In October 1833, vigilantes ransacked the latter-day saint storehouse in Independence, destroyed the printing press of the Mormon newspaper, The Evening and Morning Star, attacked their settlements on the outskirts of the city and eventually forcibly expelled them from Jackson County.

Executive paralysis permitted terrorism, which forced latter-day saints to self-defense, which was immediately labeled as an "insurrection", and was put down by the activated militia of the county.

[6] In 1834, latter-day saints attempted to effect a return to Jackson County with a quasi-military expedition known as Zion's Camp, but this effort also failed when the governor did not provide expected support.

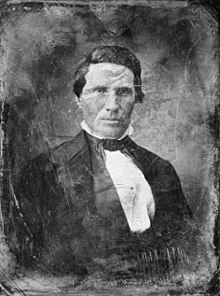

[7] Recognizing the need for a more permanent solution, Alexander William Doniphan of the Missouri legislature proposed the creation of a new county specifically for latter-day saint settlement.

[21] Two days after Rigdon's Salt Sermon, 80 prominent latter-day saints, including Hyrum Smith, signed the so-called Danite Manifesto, which warned the dissenters to "depart or a more fatal calamity shall befall you."

[27][28] Reminding Daviess County residents of the growing electoral power of that community, Peniston claimed in a speech made in Gallatin that if the Missourians "suffer such men as these [latter-day saints] to vote, you will soon lose your suffrage."

[31][5][32] When a rumor reached the latter-day saints that Judge Adam Black was gathering a mob near Millport, Joseph Smith sent Danite leaders Sampson Avrard, Cornelius Lott and Lyman Wight to his home.

"[34] The latter-day saints also visited Sheriff William Morgan and several other leading Daviess County citizens, forcing some of them to sign statements disavowing any ties to the vigilance committees as well.

[34] Black later swore an affidavit before the justice of the peace in Daviess county attesting to the treatment and threats he received from George Smith the other church members.

Atchison said further, "I would respectfully suggest to your Excellency the propriety of a visit to the scene of excitement in person, or at all events, a strong proclamation" as the only way to restore peace and the rule of law.

[54] During the days that followed, latter-day saint vigilantes under the direction of Lyman Wight drove Missourians who lived in outlying farms from their homes, which were similarly plundered and burned.

After several non-latter-day saints made statements to the authorities that Johnson had acted as a moderating influence on the Danites, he was allowed to escape rather than stand trial.

After a militia sentry shot at the crowd, the latter-day saints divided into three columns led by David W. Patten, Charles C. Rich, and James Durphee.

[78] One 19th century Missouri historian noted: The Daviess County men were very bitter against the latter-day saints, and vowed the direst vengeance on the entire sect.

The Livingston men became thoroughly imbued with the same spirit, and were eager for the raid ... feel[ing] an extraordinary sympathy for the outrages suffered by their neighbors[79]Although it had just been issued, little evidence exists that the governor's "Extermination Order" had reached the attackers.

[85] Ruth Naper swore before a justice of the peace that in early November, after the Haun's Mill Massacre, armed nonlatter-day saints billeted themselves in her home without her consent while she was living there as a widow with small children.

Elijah Reed similarly swore before a clerk of the circuit court that, fleeing for his life from a group of armed Missouri settlers, he took shelter with the Jameson family (here spelled "Jimmison").

Hyrum Smith also stated under oath before a municipal judge that after the skirmishes that destroyed houses and farmlands, the latter-day saint leadership sent a message to General Atchison and expected an army to provide protection for them.

November 1, the armed soldiers patrolling the streets of Far West were permitted enter homes, molest the people at their leisure, confiscate the firearms and ravish (rape) the women there.

Parley P. Pratt added his sworn testimony to the rapes committed when he attested before a municipal judge that he was among the group with Joseph Smith who were taken prisoner in the corn field.

The account John Murdock recorded in his journal reflects what Pratt and Smith avowed, adding that the rapes and abuse continued for as long as the latter-day saints remained in Missouri.

To William Wines Phelps, a fellow latter-day saint and witness to the events, Hinkle wrote: "When the facts were laid before Joseph, did he not say, 'I will go'; and did not the others go with him, and that, too, voluntarily, so far as you and I were concerned?

[103] Brigham Young recounts that, once the militia was disarmed, Lucas's men were turned loose on the city: [T]hey commenced their ravages by plundering the citizens of their bedding, clothing, money, wearing apparel, and every thing of value they could lay their hands upon, and also attempting to violate the chastity of the women in sight of their husbands and friends, under the pretence of hunting for prisoners and arms.

After the court martial, he ordered General Alexander William Doniphan: You will take Joseph Smith and the other prisoners into the public square of Far West and shoot them at 9 o'clock tomorrow morning.

[107]The defendants, consisting of about 60 men including Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon, were turned over to a civil court of inquiry in Richmond under Judge Austin A.

[115][116] Judge Austin A King, who had been assigned the cases of the latter-day saints charged with offenses during the conflict, warned "If you once think to plant crops or to occupy your lands any longer than the first of April, the citizens will be upon you: they will kill you every one, men, women and children.

[117] One resolution passed by the Quincy town council read: Resolved: That the gov of Missouri, in refusing protection to this class of people when pressed upon by an heartless mob, and turning upon them a band of unprincipled Militia, with orders encouraging their extermination, has brought a lasting disgrace upon the state over which he presides.

Public opinion has recoiled from a summary and forcible removal of our negro population;—much more likely will it be to revolt at the violent expulsion of two or three thousand souls, who have so many ties to connect them with us in a common brotherhood.

One historian notes that Governor Boggs was running for election against several violent men, all capable of the deed, and that there was no particular reason to suspect Rockwell of the crime.

[128] The following year, Rockwell was arrested, tried, and acquitted of the attempted murder, after a grand jury was unable to find sufficient evidence to indict him,[126] although most of Boggs' contemporaries remained convinced of his guilt.