1843 National Convention of Colored Citizens

The National Convention of Colored Citizens was held August 15–19, 1843 at the Park Presbyterian Church in Buffalo, New York.

Delegates deliberated courses of action and voted upon resolutions to further anti-slavery efforts and to help African Americans.

National colored conventions were organized to discuss changes in approaching anti-slavery actions and movements and to combine efforts between various African American groups that were spread throughout the northern states.

Colored Conventions were held in the early 1830s, but efforts to combine groups in places like New York and Philadelphia became increasingly difficult due to the differing approaches to combating slavery.

[1] The Liberty Party in 1840 advanced abolitionist movements through political action and more formal forms of persuasion.

The National Convention included delegates from Maine, Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Ohio, Michigan, Illinois, Virginia, North Carolina, and Georgia.

The appointed chair started the meeting by calling roll and reading the minutes from the previous session.

In addition, it was concluded that there are broad benefits to agriculture and that colored people in cities should be encouraged to move to farms.

President Amos G. Beman spoke out against the address on moral grounds, stating that it advocated violence.

The Emancipator and Free American paper described Garnet as "Guided by the will of Heaven, and impelled by the highest motives that man can be susceptible of.

In comparison to his peers, he held more radical and straightforward views on approaches to end slavery and to fight for equality.

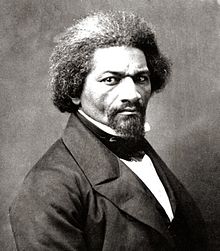

Unlike Henry Garnet, Frederick Douglass argued against the use of physical force[4] Samuel Davis gave the keynote address and set the convention in motion.

Davis' speech aimed to unify convention participants and their strategies; he emphasized that the main goal of all black citizens should be to "make known our wrongs to the world and our oppressors."

"[10] Davis called upon all attending to expand their reach to become more politically aligned with popular parties and people that would accept them and help their cause.

Continuing the speech, Davis explained the importance of fighting for the rights of all black citizens and securing happiness wherever they settle or congregate.

He said that few states recognized any rights for blacks and that members of the convention should work tenaciously to secure an elective franchise in areas they are denied and were currently subordinate to oppressive law.

[11] Davis ended his speech with a plea for attendees to unite and combine their efforts despite their differing views and factions.

Henry Highland Garnet gave a powerful speech most commonly known as the "Address to the Slaves of the United States" which was regarded widely as a call to arms and violence for the cause of freedom.

He reminded them of how slave-owners, proclaiming Christianity, captured their ancestors and brought them across the ocean where they had no future or prospects of an enjoyable and free life.

He further explained that slavery and oppression acted as a roadblock to African Americans partaking in God's blessings and the freedoms they inherited at birth: the inalienable rights at the very roots and foundation of this country.

Garnet's vision for freeing slaves included a short-term antidote of violent actions and a widespread refusal to work.

Garnet concluded his speech proposing that the motto for slaves and free Blacks alike should be a resounding cry of 'Resistance!'

His speech influenced subsequent colored conventions and anti-slavery literature to increase calls for action, especially to slaves.