Secession in the United States

[4] Historian Pauline Maier argues that this narrative asserted "the right of revolution, which was, after all, the right Americans were exercising in 1776"; and notes that Thomas Jefferson's language incorporated ideas explained at length by a long list of 17th-century writers, including John Milton, Algernon Sidney, John Locke, and other English and Scottish commentators, all of whom had contributed to the development of the Whig tradition in 18th-century Britain.

But when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing...a design to reduce them under absolute Despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such Government, and to provide new Guards for their future security.

[9]Gordon S. Wood quotes President John Adams: "Only repeated, multiplied oppressions placing it beyond all doubt that their rulers had formed settled plans to deprive them of their liberties, could warrant the concerted resistance of the people against their government".

Historian Elizabeth R. Varon wrote: [O]ne word ("disunion") contained, and stimulated, their (Americans') fears of extreme political factionalism, tyranny, regionalism, economic decline, foreign intervention, class conflict, gender disorder, racial strife, widespread violence and anarchy, and civil war, all of which could be interpreted as God's retribution for America's moral failings.

For many Americans in the North and the South, disunion was a nightmare, a tragic cataclysm that would reduce them to the kind of fear and misery that seemed to pervade the rest of the world.

[a] Because the Articles had specified a "perpetual union", various arguments have been offered to explain the apparent contradiction (and presumed illegality) of abandoning one form of government and creating another that did not include the members of the original.

James Madison of Virginia and Alexander Hamilton of New York—they who joined to vigorously promote a new Constitution—urged that renewed stability of the Union government was critically needed to protect property and commerce.

Writing in 1824, exactly midway between the fall of the Articles of Confederation and the rise of a second self-described American Confederacy, Marshal summarized the issue thusly: "Reference has been made to the political situation of these states, anterior to [the Constitution's] formation.

[25] Patrick Henry adamantly opposed adopting the Constitution because he interpreted its language to replace the sovereignty of the individual states, including that of his own Virginia.

They argued, however, that Henry exaggerated the extent to which a consolidated government was being created and that the states would serve a vital role within the new republic even though their national sovereignty was ending.

During the crisis, President Andrew Jackson, published his Proclamation to the People of South Carolina, which made a case for the perpetuity of the Union; plus, he provided his views re the questions of "revolution" and "secession":[33] But each State having expressly parted with so many powers as to constitute jointly with the other States a single nation, cannot from that period possess any right to secede, because such secession does not break a league, but destroys the unity of a nation, and any injury to that unity is not only a breach which would result from the contravention of a compact, but it is an offense against the whole Union.

[34]Some twenty-eight years after Jackson spoke, President James Buchanan gave a different voice—one much more accommodating to the views of the secessionists and the slave states—in the midst of the pre-War secession crisis.

In this manner our thirty-three States may resolve themselves into as many petty, jarring, and hostile republics, each one retiring from the Union without responsibility whenever any sudden excitement might impel them to such a course.

He argued—as one of many vociferous responses by the Jeffersonian Republicans—the sense of the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, adopted in 1798 and 1799, which reserved to those States the rights of secession and interposition (nullification).

[36] Thomas Jefferson, while sitting as Vice President of the United States in 1799, wrote to James Madison of his conviction in "a reservation of th[ose] rights resulting to us from these palpable violations [the Alien and Sedition Acts]" and, if the federal government did not return to "the true principles of our federal compact, [he was determined to] sever ourselves from that union we so much value, rather than give up the rights of self government which we have reserved, and in which alone we see liberty, safety and happiness.

[38] In writing the first Kentucky Resolution, Jefferson warned that, "unless arrested at the threshold", the Alien and Sedition Acts would "necessarily drive these states into revolution and blood".

[41] Timothy Pickering of Massachusetts and a few Federalists envisioned creating a separate New England confederation, possibly combining with lower Canada to form a new pro-British nation.

"[43] Federalist party members convened the Hartford Convention on December 15, 1814, and they addressed their opposition to the continuing war with Britain and the domination of the federal government by the "Virginia dynasty".

[44] Historian Donald R. Hickey notes: Despite pleas in the New England press for secession and a separate peace, most of the delegates taking part in the Hartford Convention were determined to pursue a moderate course.

They viewed the movements to annex Texas and to make war on Mexico as fomented by slaveholders bent on dominating Western expansion and thereby the national destiny.

New England abolitionist Benjamin Lundy argued that the annexation of Texas was "a long-premeditated crusade—set on foot by slaveholders, land speculators, etc., with the view of reestablishing, extending, and perpetuating the system of slavery and the slave trade".

The Constitution was created, he wrote, "at the expense of the colored population of the country", and Southerners were dominating the nation because of the Three-fifths Compromise; now it was time "to set the captive free by the potency of truth" and to "secede from the government".

[52] In 1846, the following volume by Henry Clarke Wright was published in London: The dissolution of the American union: demanded by justice and humanity, as the incurable enemy of liberty.

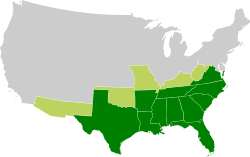

Support of secession really began to shift to Southern states from 1846, after introduction into the public debate of the Wilmot Proviso, which would have prohibited slavery in the new territories acquired from Mexico.

Southern leaders increasingly felt helpless against a powerful political group that was attacking their interests (slavery), reminiscent of Federalist alarms at the beginning of the century.

Historian Bruce Catton described President Abraham Lincoln's April 15, 1861 proclamation, three days after the attack on Fort Sumter, as a proclamation in which Lincoln defined the Union's position on the hostilities: After reciting the obvious fact that "combinations too powerful to be suppressed" by ordinary law courts and marshalls had taken charge of affairs in the seven secessionist states, it announced that the several states of the Union were called on to contribute 75,000 militia "...to suppress said combinations and to cause the laws to be duly executed."

Vice President and Senate President John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky remained until he was replaced by Hannibal Hamlin, and then expelled, but gone was the President pro tempore (Benjamin Fitzpatrick of Alabama) and the heads of the Senate committees on Claims (Alfred Iverson Sr. of Georgia), Commerce (Clement Claiborne Clay of Alabama), the District of Columbia (Albert G. Brown of Mississippi), Finance (Robert M. T. Hunter of Virginia, expelled), Foreign Relations (James M. Mason of Virginia, expelled), Military Affairs (Jefferson Davis of Mississippi), Naval Affairs (Stephen Mallory of Florida), and Public Lands (Robert Ward Johnson of Arkansas).

Thus, these scholars argue, the illegality of unilateral secession was not firmly de facto established until the Union won the Civil War; in this view, the legal question was resolved at Appomattox.

The following year, U.S. Representative Collin Peterson of Minnesota proposed legislation to allow the residents of the Northwest Angle, part of his district, to vote on seceding from the United States and joining Canada.

Respondents cited issues like gridlock, governmental overreach, the possible unconstitutionality of the Affordable Care Act and a loss of faith in the federal government as reasons for desiring secession.