3D optical data storage

No commercial product based on 3D optical data storage has yet arrived on the mass market, although several companies[which?]

The intensity or wavelength of the fluorescence is different depending on whether the media has been written at that point, and so by measuring the emitted light the data is read.

The light, therefore, addresses a large number (possibly even 109) of molecules at any one time, so the medium acts as a homogeneous mass rather than a matrix structured by the positions of chromophores.

The origins of the field date back to the 1950s, when Yehuda Hirshberg developed the photochromic spiropyrans and suggested their use in data storage.

[3] In the 1970s, Valerii Barachevskii demonstrated[4] that this photochromism could be produced by two-photon excitation, and at the end of the 1980s Peter M. Rentzepis showed that this could lead to three-dimensional data storage.

[5] A wide range of physical phenomena for data reading and recording have been investigated, large numbers of chemical systems for the medium have been developed and evaluated, and extensive work has been carried out in solving the problems associated with the optical systems required for the reading and recording of data.

Although there are many nonlinear optical phenomena, only multiphoton absorption is capable of injecting into the media the significant energy required to electronically excite molecular species and cause chemical reactions.

Two-photon absorption is the strongest multiphoton absorbance by far, but still it is a very weak phenomenon, leading to low media sensitivity.

At the focal point two-photon absorption becomes significant, because it is a nonlinear process dependent on the square of the laser fluence.

However, this approach results in a loss of nonlinearity compared to nonresonant two–photon absorbance (since each two-photon absorption step is essentially linear), and therefore risks compromising the 3D resolution of the system.

Data may be written by a nonlinear optical method, but in this case the use of very high power lasers is acceptable so media sensitivity becomes less of an issue.

However, PSHB media currently requires extremely low temperatures to be maintained in order to avoid data loss.

While some of these rely on the nonlinearity of the light-matter interaction to obtain 3D resolution, others use methods that spatially filter the media's linear response.

No absorption of light is necessary, so there is no risk of damaging data while reading, but the required refractive index mismatch in the disc may limit the thickness (i.e., number of data layers) that the media can reach due to the accumulated random wavefront errors that destroy the focused spot quality.

Media for 3D optical data storage have been suggested in several form factors: disk, card and crystal.

A credit card form factor media is attractive from the point of view of portability and convenience, but would be of a lower capacity than a disc.

Several science fiction writers have suggested small solids that store massive amounts of information, and at least in principle this could be achieved with 5D optical data storage.

Particularly when two-photon absorption is utilized, high-powered lasers may be required that can be bulky, difficult to cool, and pose safety concerns.

Therefore, as well as coping with the high laser power and variable spherical aberration, the optical system must combine and separate these different colors of light as required.

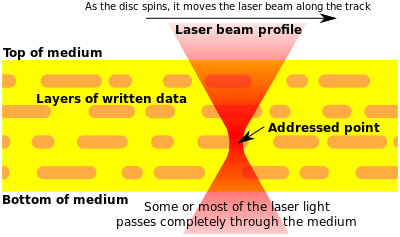

In addition, fluorescence is radiated in all directions from the addressed point, so special light collection optics must be used to maximize the signal.

Once they are identified along the z-axis, individual layers of DVD-like data may be accessed and tracked in similar ways to DVDs.

Despite the highly attractive nature of 3D optical data storage, the development of commercial products has taken a significant length of time.

In this case, the repeated reading of data may eventually serve to erase it (this also happens in phase change materials used in some DVDs).

The groups that have provided valuable input include: In addition to the academic research, several companies have been set up to commercialize 3D optical data storage and some large corporations have also shown an interest in the technology.