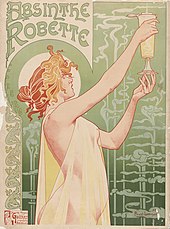

Absinthe

Absinthe (/ˈæbsɪnθ, -sæ̃θ/, French: [apsɛ̃t] ⓘ) is an anise-flavored spirit derived from several plants, including the flowers and leaves of Artemisia absinthium ("grand wormwood"), together with green anise, sweet fennel, and other medicinal and culinary herbs.

From Europe and the Americas, notable absinthe drinkers included Ernest Hemingway, James Joyce, Lewis Carroll, Charles Baudelaire, Paul Verlaine, Arthur Rimbaud, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

By 1915, absinthe had been banned in the United States and much of Europe, including France, the Netherlands, Belgium, Switzerland, and Austria-Hungary, yet it has not been demonstrated to be any more dangerous than ordinary spirits.

[11] Absinthe's revival began in the 1990s, following the adoption of modern European Union food and beverage laws that removed long-standing barriers to its production and sale.

By the early 21st century, nearly 200 brands of absinthe were being produced in a dozen countries, most notably in France, Switzerland, Austria, Germany, the Netherlands, Spain, and the Czech Republic.

According to popular legend, it began as an all-purpose patent remedy created by Dr. Pierre Ordinaire, a French doctor living in Couvet, Switzerland, around 1792 (the exact date varies by account).

It makes a ferocious beast of man, a martyr of woman, and a degenerate of the infant, it disorganizes and ruins the family and menaces the future of the country.

[26]Edgar Degas's 1876 painting L'Absinthe can be seen at the Musée d'Orsay epitomising the popular view of absinthe addicts as sodden and benumbed, and Émile Zola described its effects in his novel L'Assommoir.

Lanfray was an alcoholic who had drunk a lot of wine and brandy before the killings, but that was overlooked or ignored, and blame for the murders was placed solely on his consumption of two glasses of absinthe.

[32] The prohibition of absinthe in France eventually led to the popularity of pastis, and to a lesser extent, ouzo, and other anise-flavoured spirits that do not contain wormwood.

Similarly, Belgium lifted its long-standing ban on 1 January 2005 citing a conflict with the adopted food and beverage regulations of the single European Market.

[60][61][62] Most countries have no legal definition for absinthe, whereas the method of production and content of spirits such as whisky, brandy, and gin are globally defined and regulated.

Botanicals are initially macerated in distilled base alcohol before being redistilled to exclude bitter principles, and impart the desired complexity and texture to the spirit.

It directed the maker to "Take of the tops of wormwood, four pounds; root of angelica, calamus aromaticus, aniseed, leaves of dittany, of each one ounce; alcohol, four gallons.

Additionally, at least some cheap absinthes produced before the ban were reportedly adulterated with poisonous antimony trichloride, reputed to enhance the louching effect.

The release of these dissolved essences coincides with a perfuming of herbal aromas and flavours that "blossom" or "bloom", and brings out subtleties that are otherwise muted within the neat spirit.

As the popularity of the drink increased, additional accoutrements of preparation appeared, including the absinthe fountain, which was effectively a large jar of iced water with spigots, mounted on a lamp base.

According to popular treatises from the 19th century, absinthe could be loosely categorised into several grades (ordinaire, demi-fine, fine, and Suisse – the latter does not denote origin), in order of increasing alcoholic strength and quality.

Absinthe should not be stored in the refrigerator or freezer, as the anethole may polymerise inside the bottle, creating an irreversible precipitate, and adversely impacting the original flavour.

[92] The belief that absinthe induces hallucinogenic effects is rooted, at least partly, in the findings of 19th-century French psychiatrist Valentin Magnan, who carried out ten years of experiments with wormwood oil.

In one of the best-known written accounts of absinthe drinking, an inebriated Oscar Wilde described a phantom sensation of having tulips brush against his legs after leaving a bar at closing time.

[99] It is widely accepted that reports of hallucinogenic effects resulting from absinthe consumption were attributable to the poisonous adulterants being added to cheaper versions of the drink in the 19th century,[103] such as oil of wormwood, impure alcohol (contaminated possibly with methanol), and poisonous colouring matter – notably (among other green copper salts) cupric acetate and antimony trichloride (the last-named being used to fake the ouzo effect).

[106] Thujone, once widely believed to be an active chemical in absinthe, is a GABA antagonist, and while it can produce muscle spasms in large doses, there is no direct evidence to suggest it causes hallucinations.

[108][109][110][111] Tests conducted on mice to study toxicity showed an oral LD50 of about 45 mg thujone per kg of body weight,[112] which represents far more absinthe than could be realistically consumed.

Despite adopting sweeping EU food and beverage regulations in 1988 that effectively re-legalised absinthe, a decree was passed that same year that preserved the prohibition on products explicitly labelled as "absinthe", while placing strict limits on fenchone (fennel) and pinocamphone (hyssop)[124] in an obvious, but failed, attempt to thwart a possible return of absinthe-like products.

French producers circumvented this regulatory obstacle by labelling absinthe as spiritueux à base de plantes d'absinthe ('wormwood-based spirits'), with many either reducing or omitting fennel and hyssop altogether from their products.

A legal challenge to the scientific basis of this decree resulted in its repeal (2009),[125] which opened the door for the official French re-legalisation of absinthe for the first time since 1915.

The ban was reinforced in 1931 with harsher penalties for transgressors and remained in force until 1992 when the Italian government amended its laws to comply with the EU directive 88/388/EEC.

[133] In 2007, the Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) effectively lifted the long-standing absinthe ban, and it has since approved many brands for sale in the US market.

[149] Many other renowned artists and writers similarly drew from this cultural well, including Aleister Crowley, Ernest Hemingway, Pablo Picasso, August Strindberg, and Erik Satie.