Thermodynamic temperature

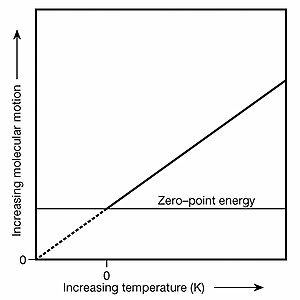

The magnitude of the kelvin was redefined in 2019 in relation to the physical property underlying thermodynamic temperature: the kinetic energy of atomic free particle motion.

However, the property that gives all gases their pressure, which is the net force per unit area on a container arising from gas particles recoiling off it, is a function of the kinetic energy borne in the freely moving atoms' and molecules' three translational degrees of freedom.

[2] Fixing the Boltzmann constant at a specific value, along with other rule making, had the effect of precisely establishing the magnitude of the unit interval of SI temperature, the kelvin, in terms of the average kinetic behavior of the noble gases.

[8][9] Notwithstanding the 2019 revision, water triple-point cells continue to serve in modern thermometry as exceedingly precise calibration references at 273.16 K and 0.01 °C.

The Boltzmann constant also relates the thermodynamic temperature of a gas to the mean kinetic energy of an individual particles' translational motion as follows:

where: While the Boltzmann constant is useful for finding the mean kinetic energy in a sample of particles, it is important to note that even when a substance is isolated and in thermodynamic equilibrium (all parts are at a uniform temperature and no heat is going into or out of it), the translational motions of individual atoms and molecules occurs across a wide range of speeds (see animation in Fig.

For instance, when scientists at the NIST achieved a record-setting cold temperature of 700 nK (billionths of a kelvin) in 1994, they used optical lattice laser equipment to adiabatically cool cesium atoms.

Importantly, the atom's translational velocity of 14.43 microns per second constitutes all its retained kinetic energy due to not being precisely at absolute zero.

This makes molecules distinct from monatomic substances (consisting of individual atoms) like the noble gases helium and argon, which have only the three translational degrees of freedom (the X, Y, and Z axis).

Gasoline can absorb a large amount of heat energy per mole with only a modest temperature change because each molecule comprises an average of 21 atoms and therefore has many internal degrees of freedom.

As can be seen in that animation, not only does momentum (heat) diffuse throughout the volume of the gas through serial collisions, but entire molecules or atoms can move forward into new territory, bringing their kinetic energy with them.

In any bulk quantity of a substance at equilibrium, black-body photons are emitted across a range of wavelengths in a spectrum that has a bell curve-like shape called a Planck curve (see graph in Fig.

The top of a Planck curve (the peak emittance wavelength) is located in a particular part of the electromagnetic spectrum depending on the temperature of the black-body.

Black-body radiation diffuses thermal energy throughout a substance as the photons are absorbed by neighboring atoms, transferring momentum in the process.

At higher temperatures, such as those found in an incandescent lamp, black-body radiation can be the principal mechanism by which thermal energy escapes a system.

This phenomenon may more easily be grasped by considering it in the reverse direction: latent heat is the energy required to break chemical bonds (such as during evaporation and melting).

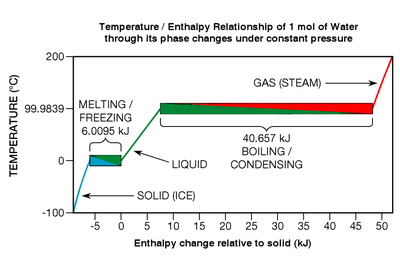

Even though thermal energy is liberated or absorbed during phase transitions, pure chemical elements, compounds, and eutectic alloys exhibit no temperature change whatsoever while they undergo them (see Fig.

If the molecular bonds in a crystal lattice are strong, the heat of fusion can be relatively great, typically in the range of 6 to 30 kJ per mole for water and most of the metallic elements.

[34] If the substance is one of the monatomic gases (which have little tendency to form molecular bonds) the heat of fusion is more modest, ranging from 0.021 to 2.3 kJ per mole.

[37] Water's sizable enthalpy of vaporization is why one's skin can be burned so quickly as steam condenses on it (heading from red to green in Fig.

A further complication is that many solids change their crystal structure to more compact arrangements at extremely high pressures (up to millions of bars, or hundreds of gigapascals).

By expressing variables in absolute terms and applying Gay-Lussac's law of temperature/pressure proportionality, solutions to everyday problems are straightforward; for instance, calculating how a temperature change affects the pressure inside an automobile tire.

The thermodynamic temperature can be shown to have special properties, and in particular can be seen to be uniquely defined (up to some constant multiplicative factor) by considering the efficiency of idealized heat engines.

Guillaume Amontons (1663–1705) published two papers in 1702 and 1703 that may be used to credit him as being the first researcher to deduce the existence of a fundamental (thermodynamic) temperature scale featuring an absolute zero.

In his paper Observations of two persistent degrees on a thermometer, he recounted his experiments showing that ice's melting point was effectively unaffected by pressure.

Notwithstanding the work of Guillaume Amontons 85 years earlier, Jacques Alexandre César Charles (1746–1823) is often credited with discovering (circa 1787), but not publishing, that the volume of a gas under constant pressure is proportional to its absolute temperature.

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850) published work in 1802 (acknowledging the unpublished lab notes of Jacques Charles fifteen years earlier) describing how the volume of gas under constant pressure changes linearly with its absolute (thermodynamic) temperature.

Ludwig Boltzmann (1844–1906) made major contributions to thermodynamics between 1877 and 1884 through an understanding of the role that particle kinetics and black body radiation played.

In November 2018, the 26th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) changed the definition of the Kelvin by fixing the Boltzmann constant to 1.380649×10−23 when expressed in the unit J/K.

Note too that absolute zero serves as the baseline atop which thermodynamics and its equations are founded because they deal with the exchange of thermal energy between "systems" (a plurality of particles and fields modeled as an average).