Iridium

The dominant uses of iridium are the metal itself and its alloys, as in high-performance spark plugs, crucibles for recrystallization of semiconductors at high temperatures, and electrodes for the production of chlorine in the chloralkali process.

[10] For this reason, the unusually high abundance of iridium in the clay layer at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary gave rise to the Alvarez hypothesis that the impact of a massive extraterrestrial object caused the extinction of non-avian dinosaurs and many other species 66 million years ago, now known to be produced by the impact that formed the Chicxulub crater.

Similarly, an iridium anomaly in core samples from the Pacific Ocean suggested the Eltanin impact of about 2.5 million years ago.

Because of its hardness, brittleness, and very high melting point, solid iridium is difficult to machine, form, or work; thus powder metallurgy is commonly employed instead.

Despite these limitations and iridium's high cost, a number of applications have developed where mechanical strength is an essential factor in some of the extremely severe conditions encountered in modern technology.

[18] Iridium is extremely brittle, to the point of being hard to weld because the heat-affected zone cracks, but it can be made more ductile by addition of small quantities of titanium and zirconium (0.2% of each apparently works well).

Hexachloroiridic (IV) acid, H2IrCl6, and its ammonium salt are common iridium compounds from both industrial and preparative perspectives.

The first European reference to platinum appears in 1557 in the writings of the Italian humanist Julius Caesar Scaliger as a description of an unknown noble metal found between Darién and Mexico, "which no fire nor any Spanish artifice has yet been able to liquefy".

[45] In 1735, Antonio de Ulloa and Jorge Juan y Santacilia saw Native Americans mining platinum while the Spaniards were travelling through Colombia and Peru for eight years.

[44] In 1741, Charles Wood,[46] a British metallurgist, found various samples of Colombian platinum in Jamaica, which he sent to William Brownrigg for further investigation.

[47] Brownrigg also made note of platinum's extremely high melting point and refractory metal-like behaviour toward borax.

Other chemists across Europe soon began studying platinum, including Andreas Sigismund Marggraf,[48] Torbern Bergman, Jöns Jakob Berzelius, William Lewis, and Pierre Macquer.

In 1752, Henrik Scheffer published a detailed scientific description of the metal, which he referred to as "white gold", including an account of how he succeeded in fusing platinum ore with the aid of arsenic.

[44] Chemists who studied platinum dissolved it in aqua regia (a mixture of hydrochloric and nitric acids) to create soluble salts.

[13] The French chemists Victor Collet-Descotils, Antoine François, comte de Fourcroy, and Louis Nicolas Vauquelin also observed the black residue in 1803, but did not obtain enough for further experiments.

Vauquelin treated the powder alternately with alkali and acids[22] and obtained a volatile new oxide, which he believed to be of this new metal—which he named ptene, from the Greek word πτηνός ptēnós, "winged".

[50] He named iridium after Iris (Ἶρις), the Greek winged goddess of the rainbow and the messenger of the Olympian gods, because many of the salts he obtained were strongly colored.

[13][52] British scientist John George Children was the first to melt a sample of iridium in 1813 with the aid of "the greatest galvanic battery that has ever been constructed" (at that time).

In 1880, John Holland and William Lofland Dudley were able to melt iridium by adding phosphorus and patented the process in the United States; British company Johnson Matthey later stated they had been using a similar process since 1837 and had already presented fused iridium at a number of World Fairs.

[13] In Munich, Germany in 1957 Rudolf Mössbauer, in what has been called one of the "landmark experiments in twentieth-century physics",[53] discovered the resonant and recoil-free emission and absorption of gamma rays by atoms in a solid metal sample containing only 191Ir.

[54] This phenomenon, known as the Mössbauer effect resulted in the awarding of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1961, at the age 32, just three years after he published his discovery.

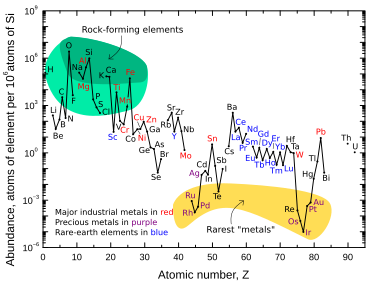

[60] In contrast to its low abundance in crustal rock, iridium is relatively common in meteorites, with concentrations of 0.5 ppm or more.

[22] In nickel and copper deposits, the platinum group metals occur as sulfides, tellurides, antimonides, and arsenides.

[69] Iridium in sediments can come from cosmic dust, volcanoes, precipitation from seawater, microbial processes, or hydrothermal vents,[69] and its abundance can be strongly indicative of the source.

[71][72] For example, core samples from the Pacific Ocean with elevated iridium levels suggested the Eltanin impact of about 2.5 million years ago.

[73] The Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary of 66 million years ago, marking the temporal border between the Cretaceous and Paleogene periods of geological time, was identified by a thin stratum of iridium-rich clay.

[74] A team led by Luis Alvarez proposed in 1980 an extraterrestrial origin for this iridium, attributing it to an asteroid or comet impact.

The main areas of use are electrodes for producing chlorine and other corrosive products, OLEDs, crucibles, catalysts (e.g. acetic acid), and ignition tips for spark plugs.

Such crucibles are used in the Czochralski process to produce oxide single-crystals (such as sapphires) for use in computer memory devices and in solid state lasers.

Those who know the constant trouble and expense which are occasioned by the wearing of the vent-pieces of cannon when in active service, will appreciate this important adaptation".