Abundance of the chemical elements

The abundance of chemical elements in the universe is dominated by the large amounts of hydrogen and helium which were produced during Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

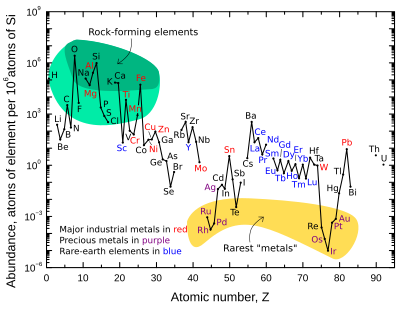

Elements with even atomic numbers are generally more common than their neighbors in the periodic table, due to their favorable energetics of formation, described by the Oddo–Harkins rule.

The abundance of elements in specialized environments, such as atmospheres, oceans, or the human body, are primarily a product of chemical interactions with the medium in which they reside.

The abundance of chemical elements in the universe is dominated by the large amounts of hydrogen and helium which were produced during Big Bang nucleosynthesis.

Lithium, beryllium, and boron, despite their low atomic number, are rare because, although they are produced by nuclear fusion, they are destroyed by other reactions in the stars.

[4][5] Their natural occurrence is the result of cosmic ray spallation of carbon, nitrogen and oxygen in a type of nuclear fission reaction.

The Segrè plot is initially linear because (aside from hydrogen) the vast majority of ordinary matter (99.4% in the Solar System[6]) contains an equal number of protons and neutrons (Z=N).

Despite comprising only a very small fraction of the universe, the remaining "heavy elements" can greatly influence astronomical phenomena.

Iron-56 is particularly common, since it is the most stable nuclide (in that it has the highest nuclear binding energy per nucleon) and can easily be "built up" from alpha particles (being a product of decay of radioactive nickel-56, ultimately made from 14 helium nuclei).

Elements heavier than iron are made in energy-absorbing processes in large stars, and their abundance in the universe (and on Earth) generally decreases with increasing atomic number.

The table shows the ten most common elements in our galaxy (estimated spectroscopically), as measured in parts per million, by mass.

[3] Nearby galaxies that have evolved along similar lines have a corresponding enrichment of elements heavier than hydrogen and helium.

Since physical laws and processes are apparently uniform throughout the universe, however, it is expected that these galaxies will likewise have evolved similar abundances of elements.

They are produced in small quantities by nuclear fusion in dying stars or by breakup of heavier elements in interstellar dust, caused by cosmic ray spallation.

Additionally, the alternation in the nuclear binding energy between even and odd atomic numbers resolves above oxygen as the graph increases steadily up to its peak at iron.

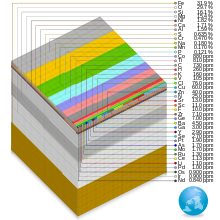

By mass, it is composed mostly of iron (32.1%), oxygen (30.1%), silicon (15.1%), magnesium (13.9%), sulfur (2.9%), nickel (1.8%), calcium (1.5%), and aluminium (1.4%); with the remaining 1.2% consisting of trace amounts of other elements.

[16] The bulk composition of the Earth by elemental mass is roughly similar to the gross composition of the solar system, with the major differences being that Earth is missing a great deal of the volatile elements hydrogen, helium, neon, and nitrogen, as well as carbon which has been lost as volatile hydrocarbons.

The mass-abundance of the nine most abundant elements in the Earth's crust is roughly: oxygen 46%, silicon 28%, aluminium 8.3%, iron 5.6%, calcium 4.2%, sodium 2.5%, magnesium 2.4%, potassium 2.0%, and titanium 0.61%.

The eight naturally occurring very rare, highly radioactive elements (polonium, astatine, francium, radium, actinium, protactinium, neptunium, and plutonium) are not included, since any of these elements that were present at the formation of the Earth have decayed eons ago, and their quantity today is negligible and is only produced from radioactive decay of uranium and thorium.

[18] Other cosmically common elements such as hydrogen, carbon and nitrogen form volatile compounds such as ammonia and methane that easily boil away into space from the heat of planetary formation and/or the Sun's light.

The more abundant rare earth elements are similarly concentrated in the crust compared to commonplace industrial metals such as chromium, nickel, copper, zinc, molybdenum, tin, tungsten, or lead.

However, in contrast to the ordinary base and precious metals, rare earth elements have very little tendency to become concentrated in exploitable ore deposits.

The mass-abundance of the seven most abundant elements in the Earth's mantle is approximately: oxygen 44.3%, magnesium 22.3%, silicon 21.3%, iron 6.32%, calcium 2.48%, aluminium 2.29%, nickel 0.19%.

[19] Due to mass segregation, the core of the Earth is believed to be primarily composed of iron (88.8%), with smaller amounts of nickel (5.8%), sulfur (4.5%), and less than 1% trace elements.

[6] The most abundant elements in the ocean by proportion of mass in percent are oxygen (85.84%), hydrogen (10.82%), chlorine (1.94%), sodium (1.08%), magnesium (0.13%), sulfur (0.09%), calcium (0.04%), potassium (0.04%), bromine (0.007%), carbon (0.003%), and boron (0.0004%).

By mass, human cells consist of 65–90% water (H2O), and a significant portion of the remainder is composed of carbon-containing organic molecules.

Almost 99% of the mass of the human body is made up of six elements: hydrogen (H), carbon (C), nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), calcium (Ca), and phosphorus (P) .

[22] In the case of the lanthanides, the definition of an essential nutrient as being indispensable and irreplaceable is not completely applicable due to their extreme similarity.