Acala

[6] Acala (as Fudō) is one of the especially important and well-known divinities in Japanese Buddhism, being especially venerated in the Shingon, Tendai, Zen, and Nichiren sects, as well as in Shugendō.

[8][9]More well-known, however, is the following passage from the Mahāvairocana Tantra (also known as the Mahāvairocanābhisaṃbodhi Tantra or the Vairocana Sūtra) which refers to Acala as one of the deities of the Womb Realm Mandala: Below the mantra-lord (i.e., Vairocana), in the direction of Nairṛti (i.e., southwest), Is Acala, the Tathāgata's servant (不動如來使): he holds a wisdom sword and a noose (pāśa), The hair from the top of his head hangs down on his left shoulder, and with one eye he looks fixedly; Awesomely wrathful, his body [is enveloped in] fierce flames, and he rests on a rock; His face is marked with [a frown like] waves on water, and he has the figure of a stout young boy.

[10][8][11] The deity was apparently popular in India during the 8th-9th centuries as evident by the fact that six of the Sanskrit texts translated by the esoteric master Amoghavajra into Chinese are devoted entirely to him.

[3] Indeed, Acala's rise to a more prominent position in the Esoteric pantheon in East Asian Buddhism may be credited in part to the writings of Amoghavajra and his teacher Vajrabodhi.

[16] In a commentary on the Mahāvairocana Tantra by Yi Xing, he is said to have manifested in the world following Vairocana's vow to save all beings, and that his primary function is to remove obstacles to enlightenment.

[23][4] By contrast, the sanrinjin (三輪身, "bodies of the three wheels") theory, based on Amoghavajra's writings and prevalent in Japanese esoteric Buddhism (Mikkyō), interprets Acala as an incarnation of Vairocana.

""embodiments of the wheel of injunction") of the Five Great Buddhas, who appear both as gentle bodhisattvas to teach the Dharma and also as fierce wrathful deities to subdue and convert hardened nonbelievers.

However, this interpretation, while common in Japan, is not necessarily universal: in Nichiren-shū, for instance, Acala and Rāgarāja (Aizen Myōō), the two vidyārājas who commonly feature in the mandalas inscribed by Nichiren, are seen as protective deities (外護神, gegoshin) who respectively embody the two tenets of hongaku ("original enlightenment") doctrine: "life and death (saṃsāra) are precisely nirvana" (生死即涅槃, shōji soku nehan) and "worldly passions (kleśa) are precisely enlightenment (bodhi)" (煩悩即菩提, bonnō soku bodai).

"His right hand is terrifying with a sword in it, His left is holding a noose; He is making a threatening gesture with his index finger, And bites his lower lip with his fangs.

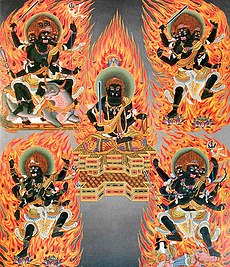

"[18] In Nepalese and Tibetan art, Acala is usually shown either kneeling on his left knee or standing astride, bearing a noose or lasso (pāśa) and an upraised sword.

"Ruler of Hindrances", a Buddhist equivalent to the Hindu god Ganesha, albeit interpreted negatively as one who causes obstacles), signifying his role as the destroyer of impediments to enlightenment.

[3][34] By contrast, portrayals of Acala (Fudō) in Japan generally tend to conform to the description given in the Amoghapāśakalparāja Sūtra and the Mahāvairocana Tantra: holding a lasso and a sword while sitting or standing on a rock (盤石座, banjakuza) or a pile of hewn stones (瑟瑟座, shitsushitsuza), with his braided hair hanging from the left of his head.

[38] Unlike the South Asian Acala, whose striding posture conveys movement and dynamism, the Japanese Fudō sits or stands erect, suggesting motionlessness and rigidity.

The first type (observable in the earliest extant Japanese images of the deity) shows him with wide open, glaring eyes, straight hair braided in rows and two fangs pointed in the same direction; a lotus flower rests above his head.

[37][43][44][45] Although the squinting left eye and inverted fangs of the second type ultimately derives from the description of Acala given in the Mahāvairocana Tantra and Yi Xing's commentary on the text ("with his lower [right] tooth he bites the upper-right side of his lip, and with his left [-upper tooth he bites] his lower lip which sticks out"), these attributes were mostly absent in Chinese and earlier Japanese icons.

In Tibet, for instance, a variant of the kneeling Acala depiction shows him as being white in hue "like sunrise on a snow mountain reflecting many rays of light".

The most famous example of the Aka-Fudō portrayal is a painting kept at Myōō-in on Mount Kōya (Wakayama Prefecture) traditionally attributed to the Heian period Tendai monk Enchin.

[52][53][54] The most well-known image of the Ki-Fudō type, meanwhile, is enshrined in Mii-dera (Onjō-ji) at the foot of Mount Hiei in Shiga Prefecture and is said to have been based on another vision that Enchin saw while practicing austerities in 838.

[92] The cult of Acala was first brought to Japan by the esoteric master Kūkai, the founder of the Shingon school, and his successors, where it developed as part of the growing popularity of rituals for the protection of the state.

While Acala was at first simply regarded as the primus inter pares among the five wisdom kings, he gradually became a focus of worship in his own right, subsuming characteristics of the other four vidyarājas (who came to be perceived as emanating from him), and became installed as the main deity (honzon) at many temples and outdoor shrines.

Many eminent Buddhist priests like Kūkai, Kakuban, Ennin, Enchin, and Sōō worshiped Acala as their patron deity, and stories of how he miraculously rescued his devotees in times of danger were widely circulated.

[94] At temples dedicated to Acala, priests perform the Fudō-hō (不動法), or ritual service to enlist the deity's power of purification to benefit the faithful.

Lay persons or monks in yamabushi gear who go into rigorous training outdoors in the mountains often pray to small Acala statues or portable talismans that serve as his honzon.

He is also frequently invoked during Chinese Buddhist repentance ceremonies, such as the Liberation Rite of Water and Land, along with the other Wisdom Kings where they are given offerings and intreated to expel evil from the ritual platform.