Adaptive immune system

Sometimes the adaptive system is unable to distinguish harmful from harmless foreign molecules; the effects of this may be hayfever, asthma, or any other allergy.

This acquired response is called "adaptive" because it prepares the body's immune system for future challenges (though it can actually also be maladaptive when it results in allergies or autoimmunity).

First, somatic hypermutation is a process of accelerated random genetic mutations in the antibody-coding genes, which allows antibodies with novel specificity to be created.

Most textbooks today, following the early use by Janeway, use "adaptive" almost exclusively and noting in glossaries that the term is synonymous with "acquired".

In the last decade, the term "adaptive" has been increasingly applied to another class of immune response not so-far associated with somatic gene rearrangements.

The peripheral bloodstream contains only 2% of all circulating lymphocytes; the other 98% move within tissues and the lymphatic system, which includes the lymph nodes and spleen.

[2] In humans, approximately 1–2% of the lymphocyte pool recirculates each hour to increase the opportunity for the cells to encounter the specific pathogen and antigen that they react to.

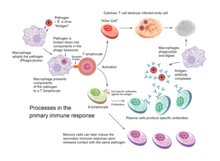

The acquired immune response is triggered by recognizing foreign antigen in the cellular context of an activated dendritic cell.

[3] Dendritic cells engulf exogenous pathogens, such as bacteria, parasites or toxins in the tissues and then migrate, via chemotactic signals, to the T cell-enriched lymph nodes.

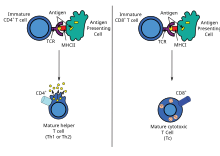

The host cell uses enzymes to digest virally associated proteins and displays these pieces on its surface to T-cells by coupling them to MHC.

[3] Naive cytotoxic T cells are activated when their T-cell receptor (TCR) strongly interacts with a peptide-bound MHC class I molecule.

[3] Once activated, the CTL undergoes a process called clonal selection, in which it gains functions and divides rapidly to produce an army of "armed" effector cells.

Activated CTL then travels throughout the body searching for cells that bear that unique MHC Class I + peptide.

Increasingly, there is strong evidence from mouse and human-based scientific studies of a broader diversity in CD4+ effector T helper cell subsets.

On one hand, γδ T cells may be considered a component of adaptive immunity in that they rearrange TCR genes via V(D)J recombination, which also produces junctional diversity, and develop a memory phenotype.

Antibodies (also known as immunoglobulin, Ig), are large Y-shaped proteins used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects.

[18] Other experimental model based on red flour beetle also showed pathogen specific primed memory transfer into offspring from both mothers and fathers.

Last one is piRNA where small RNA binds to the Piwi protein family and controls transposones and other mobile elements.

This is "adaptive" in the sense that the body's immune system prepares itself for future challenges, but is "maladaptive" of course if the receptors are autoimmune.

In utero, maternal IgG is transported directly across the placenta, so that, at birth, human babies have high levels of antibodies, with the same range of antigen specificities as their mother.

[2][3] According to the clonal selection theory, at birth, an animal randomly generates a vast diversity of lymphocytes (each bearing a unique antigen receptor) from information encoded in a small family of genes.

The first is that the fetus occupies a portion of the body protected by a non-immunological barrier, the uterus, which the immune system does not routinely patrol.

[3] A more modern explanation for this induction of tolerance is that specific glycoproteins expressed in the uterus during pregnancy suppress the uterine immune response (see eu-FEDS).

It is believed that the ancestors of modern viviparous mammals evolved after an infection by this virus, enabling the fetus to survive the immune system of the mother.

One of the most interesting developments in biomedical science during the past few decades has been elucidation of mechanisms mediating innate immunity.

[36] Repeated malaria infections strengthen acquired immunity and broaden its effects against parasites expressing different surface antigens.

These observations raise questions about mechanisms that favor the survival of most children in Africa while allowing some to develop potentially lethal infections.

[37] The acquired immune system, which has been best-studied in mammals, originated in jawed fish approximately 500 million years ago.

The evolution of the AIS, based on Ig, TCR, and MHC molecules, is thought to have arisen from two major evolutionary events: the transfer of the RAG transposon (possibly of viral origin) and two whole genome duplications.

Jawless fishes have a different AIS that relies on gene rearrangement to generate diverse immune receptors with a functional dichotomy that parallels Ig and TCR molecules.