Acute pancreatitis

[2] Mild cases are usually successfully treated with conservative measures such as hospitalization with intravenous fluid infusion, pain control, and early enteral feeding.

[2] 35% develop exocrine pancreatic insufficiency in which the pancreas is unable to secrete digestive enzymes due to structural damage, leading to malabsorption.

[2] Common symptoms of acute pancreatitis include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and low to moderate grade fever.

[2][3] The abdominal pain is the most common symptom and it is usually described as being in the left upper quadrant, epigastric area or around the umbilicus, with radiation throughout the abdomen, or to the chest or back.

[6] Pleural effusions (fluid in the lung cavity) may occur in up to 34% of people with acute pancreatitis and are associated with a poor prognosis.

[9][2] Systemic complications include acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome, disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), hypocalcemia (from fat saponification), hyperglycemia and insulin dependent diabetes mellitus (from pancreatic insulin-producing beta cell damage), and malabsorption due to exocrine failure.

This occurs through inappropriate activation of inactive enzyme precursors called zymogens (or proenzymes) inside the pancreas, most notably trypsinogen.

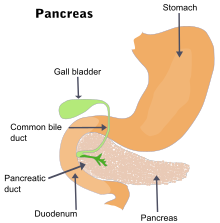

Normally, trypsinogen is converted to its active form (trypsin) in the first part of the small intestine (duodenum), where the enzyme assists in the digestion of proteins.

The death of pancreatic cells occurs via two main mechanisms: apoptosis, which is physiologically controlled, and necrosis, which is less organized and more damaging.

Lipase activation produces the necrosis of fat tissue in pancreatic interstitium and peripancreatic spaces as well as vessel damage.

[18] Another study found that the amylase could add diagnostic value to the lipase, but only if the results of the two tests were combined with a discriminant function equation.

[20] The differential diagnosis includes:[21] Regarding the need for computed tomography, practice guidelines state: CT is an important common initial assessment tool for acute pancreatitis.

Pancreatic necrosis can be reliably identified by intravenous contrast-enhanced CT imaging,[22] and is of value if infection occurs and surgical or percutaneous debridement is indicated.

[24] Additional utility of MRI includes its indication for imaging of patients with an allergy to CT's contrast material, and an overall greater sensitivity to hemorrhage, vascular complications, pseudoaneurysms, and venous thrombosis.

MRCP provides useful information regarding the etiology of acute pancreatitis, i.e., the presence of tiny biliary stones (choledocholithiasis or cholelithiasis) and duct anomalies.

[24] Clinical trials indicate that MRCP can be as effective a diagnostic tool for acute pancreatitis with biliary etiology as endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, but with the benefits of being less invasive and causing fewer complications.

[2] Isotonic crystalloid solutions (such as lactated ringers) are preferred over normal saline for fluid resuscitation and are associated with a lower risk of developing systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS).

[2] In the initial stages (within the first 12 to 24 hours) of acute pancreatitis, fluid replacement has been associated with a reduction in morbidity and mortality.

[33] In addition, meperidine has a short half-life and repeated doses can lead to accumulation of the metabolite normeperidine, which causes neuromuscular side effects and, rarely, seizures.

Acute pancreatitis is a catabolic state and with hemodynamic instability or fluid shifts or edema there may be reduced intravascular perfusion to the gut.

[2] Enteral nutrition gives one needed caloric intake as well as enhances intestinal motility and blood flow to the gut, reducing these risks.

[39] If a gallstone is detected, ERCP, performed within 24 to 72 hours of presentation with successful removal of the stone, is known to reduce morbidity and mortality.

[2] Two such scoring systems are the Ranson criteria and APACHE II (Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation) indices.

[45] Some experts recommend using the APACHE II score as well as a serum hematocrit level early during the admission as prognostic indicators.

The criteria for point assignment is that a certain breakpoint be met at any time during that 48 hour period, so that in some situations it can be calculated shortly after admission.

[47][48][49] However, a few studies indicate that CTSI is not significantly associated with the prognosis of hospitalization in patients with pancreatic necrosis, nor is it an accurate predictor of AP severity.

It is scored through the mnemonic, PANCREAS: Predicts mortality risk in pancreatitis with fewer variables than Ranson's criteria.