Aerodynamics

Most of the early efforts in aerodynamics were directed toward achieving heavier-than-air flight, which was first demonstrated by Otto Lilienthal in 1891.

[2] Since then, the use of aerodynamics through mathematical analysis, empirical approximations, wind tunnel experimentation, and computer simulations has formed a rational basis for the development of heavier-than-air flight and a number of other technologies.

Recent work in aerodynamics has focused on issues related to compressible flow, turbulence, and boundary layers and has become increasingly computational in nature.

Modern aerodynamics only dates back to the seventeenth century, but aerodynamic forces have been harnessed by humans for thousands of years in sailboats and windmills,[3] and images and stories of flight appear throughout recorded history,[4] such as the Ancient Greek legend of Icarus and Daedalus.

[6] In 1726, Sir Isaac Newton became the first person to develop a theory of air resistance,[7] making him one of the first aerodynamicists.

In 1871, Francis Herbert Wenham constructed the first wind tunnel, allowing precise measurements of aerodynamic forces.

Drag theories were developed by Jean le Rond d'Alembert,[13] Gustav Kirchhoff,[14] and Lord Rayleigh.

[15] In 1889, Charles Renard, a French aeronautical engineer, became the first person to reasonably predict the power needed for sustained flight.

Building on these developments as well as research carried out in their own wind tunnel, the Wright brothers flew the first powered airplane on December 17, 1903.

During the time of the first flights, Frederick W. Lanchester,[17] Martin Kutta, and Nikolai Zhukovsky independently created theories that connected circulation of a fluid flow to lift.

Macquorn Rankine and Pierre Henri Hugoniot independently developed the theory for flow properties before and after a shock wave, while Jakob Ackeret led the initial work of calculating the lift and drag of supersonic airfoils.

This rapid increase in drag led aerodynamicists and aviators to disagree on whether supersonic flight was achievable until the sound barrier was broken in 1947 using the Bell X-1 aircraft.

By the time the sound barrier was broken, aerodynamicists' understanding of the subsonic and low supersonic flow had matured.

These properties may be directly or indirectly measured in aerodynamics experiments or calculated starting with the equations for conservation of mass, momentum, and energy in air flows.

Unlike liquids and solids, gases are composed of discrete molecules which occupy only a small fraction of the volume filled by the gas.

On a molecular level, flow fields are made up of the collisions of many individual of gas molecules between themselves and with solid surfaces.

However, in most aerodynamics applications, the discrete molecular nature of gases is ignored, and the flow field is assumed to behave as a continuum.

The continuum assumption is less valid for extremely low-density flows, such as those encountered by vehicles at very high altitudes (e.g. 300,000 ft/90 km)[6] or satellites in Low Earth orbit.

In those cases, statistical mechanics is a more accurate method of solving the problem than is continuum aerodynamics.

The Knudsen number can be used to guide the choice between statistical mechanics and the continuous formulation of aerodynamics.

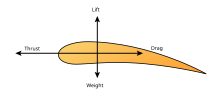

Evaluating the lift and drag on an airplane or the shock waves that form in front of the nose of a rocket are examples of external aerodynamics.

For instance, internal aerodynamics encompasses the study of the airflow through a jet engine or through an air conditioning pipe.

In air, compressibility effects are usually ignored when the Mach number in the flow does not exceed 0.3 (about 335 feet (102 m) per second or 228 miles (366 km) per hour at 60 °F (16 °C)).

The term Transonic refers to a range of flow velocities just below and above the local speed of sound (generally taken as Mach 0.8–1.2).

The presence of shock waves, along with the compressibility effects of high-flow velocity (see Reynolds number) fluids, is the central difference between the supersonic and subsonic aerodynamics regimes.

Aerodynamics is a significant element of vehicle design, including road cars and trucks where the main goal is to reduce the vehicle drag coefficient, and racing cars, where in addition to reducing drag the goal is also to increase the overall level of downforce.

The field of environmental aerodynamics describes ways in which atmospheric circulation and flight mechanics affect ecosystems.

Sports in which aerodynamics are of crucial importance include soccer, table tennis, cricket, baseball, and golf, in which most players can control the trajectory of the ball using the "Magnus effect".