Brass

It has also been widely used to make sculpture and utensils because of its low melting point, high workability (both with hand tools and with modern turning and milling machines), durability, and electrical and thermal conductivity.

Brass is still commonly used in applications where corrosion resistance and low friction are required, such as locks, hinges, gears, bearings, ammunition casings, zippers, plumbing, hose couplings, valves, SCUBA regulators, and electrical plugs and sockets.

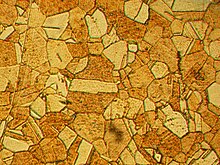

Since lead has a lower melting point than the other constituents of the brass, it tends to migrate towards the grain boundaries in the form of globules as it cools from casting.

Keys plated with other metals are not affected by the settlement, and may continue to use brass alloys with a higher percentage of lead content.

This brass alloy must be produced with great care, with special attention placed on a balanced composition and proper production temperatures and parameters to avoid long-term failures.

[24] The high malleability and workability, relatively good resistance to corrosion, and traditionally attributed acoustic properties of brass, have made it the usual metal of choice for construction of musical instruments whose acoustic resonators consist of long, relatively narrow tubing, often folded or coiled for compactness; silver and its alloys, and even gold, have been used for the same reasons, but brass is the most economical choice.

For the same reason, some low clarinets, bassoons and contrabassoons feature a hybrid construction, with long, straight sections of wood, and curved joints, neck, and/or bell of metal.

Such alloys are stiffer and more durable than the brass used to construct the instrument bodies, but still workable with simple hand tools—a boon to quick repairs.

The problem was caused by high residual stresses from cold forming of the cases during manufacture, together with chemical attack from traces of ammonia in the atmosphere.

[58][59] In West Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean early copper-zinc alloys are now known in small numbers from a number of 3rd millennium BC sites in the Aegean, Iraq, the United Arab Emirates, Kalmykia, Turkmenistan and Georgia and from 2nd millennium BC sites in western India, Uzbekistan, Iran, Syria, Iraq and Canaan.

[62] However the large number of copper-zinc alloys now known suggests that at least some were deliberately manufactured and many have zinc contents of more than 12% wt which would have resulted in a distinctive golden colour.

[68] X-ray fluorescence analysis of 39 orichalcum ingots recovered from a 2,600-year-old shipwreck off Sicily found them to be an alloy made with 75–80% copper, 15–20% zinc and small percentages of nickel, lead and iron.

[69][70] During the later part of first millennium BC the use of brass spread across a wide geographical area from Britain[71] and Spain[72] in the west to Iran, and India in the east.

[73] This seems to have been encouraged by exports and influence from the Middle East and eastern Mediterranean where deliberate production of brass from metallic copper and zinc ores had been introduced.

[74] The 4th century BC writer Theopompus, quoted by Strabo, describes how heating earth from Andeira in Turkey produced "droplets of false silver", probably metallic zinc, which could be used to turn copper into oreichalkos.

[78] However it is now thought this was probably a deliberate change in composition[87] and overall the use of brass increases over this period making up around 40% of all copper alloys used in the Roman world by the 4th century AD.

[89] However other alloys such as low tin bronze were also used and they vary depending on local cultural attitudes, the purpose of the metal and access to zinc, especially between the Islamic and Byzantine world.

The baptismal font at St Bartholomew's Church, Liège in modern Belgium (before 1117) is an outstanding masterpiece of Romanesque brass casting, though also often described as bronze.

[96] Latten is a term for medieval alloys of uncertain and often variable composition often covering decorative borders and similar objects cut from sheet metal, whether of brass or bronze.

[98] A number of Islamic writers and the 13th century Italian Marco Polo describe how this was obtained by sublimation from zinc ores and condensed onto clay or iron bars, archaeological examples of which have been identified at Kush in Iran.

In 10th century Yemen al-Hamdani described how spreading al-iglimiya, probably zinc oxide, onto the surface of molten copper produced tutiya vapor which then reacted with the metal.

[100] The 13th century Iranian writer al-Kashani describes a more complex process whereby tutiya was mixed with raisins and gently roasted before being added to the surface of the molten metal.

[103] Albertus Magnus noted that the "power" of both calamine and tutty could evaporate and described how the addition of powdered glass could create a film to bind it to the metal.

[104] German brass making crucibles are known from Dortmund dating to the 10th century AD and from Soest and Schwerte in Westphalia dating to around the 13th century confirm Theophilus' account, as they are open-topped, although ceramic discs from Soest may have served as loose lids which may have been used to reduce zinc evaporation, and have slag on the interior resulting from a liquid process.

[105] Some of the most famous objects in African art are the lost wax castings of West Africa, mostly from what is now Nigeria, produced first by the Kingdom of Ife and then the Benin Empire.

[106] Work in brass or bronze continued to be important in Benin art and other West African traditions such as Akan goldweights, where the metal was regarded as a more valuable material than in Europe.

[109] The crucible lids had small holes which were blocked with clay plugs near the end of the process presumably to maximize zinc absorption in the final stages.

[116] The European brass industry continued to flourish into the post medieval period buoyed by innovations such as the 16th century introduction of water powered hammers for the production of wares such as pots.

[117] After several false starts during the 16th and 17th centuries the brass industry was also established in England taking advantage of abundant supplies of cheap copper smelted in the new coal fired reverberatory furnace.

[118] In 1723 Bristol brass maker Nehemiah Champion patented the use of granulated copper, produced by pouring molten metal into cold water.