Air well (condenser)

Rather, plants are able to absorb dew directly from their leaves, and the main benefit of a stone mulch is to reduce water loss from the soil and to eliminate competition from weeds.

In 1900, near the site of the ancient Byzantine city of Theodosia, thirteen large piles of stones were discovered by Zibold, who was a forester and engineer in charge of the area.

[14] To verify his hypothesis, Zibold constructed a stone-pile condenser at an altitude of 288 metres (945 ft) on mount Tepe-Oba near the ancient site of Theodosia.

When he retired in 1946, he put the condenser out of order, possibly because he did not want to leave an improper installation to mislead those who might later continue studies on air wells.

Although the system apparently worked, it was expensive, and Klaphake finally adopted a more compact design based on a masonry structure.

[17] According to Klaphake: The building produces water during the day and cools itself during the night; when the sun rises, the warm air is drawn through the upper holes into the building by the out-flowing cooler air, becomes cooled on the cold surface, deposits its water, which then oozes down and is collected somewhere underneath.

At Cook, the railway company had previously installed a large coal-powered active condenser,[21] but it was prohibitively expensive to run, and it was cheaper to simply transport water.

[1][26] Beginning in 1930, Knapen's dew tower took 18 months to build; it still stands today, albeit in dilapidated condition.

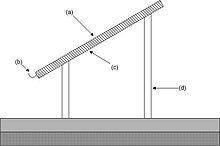

[30] In the early 1960s, dew condensers made from sheets of polyethylene supported on a simple frame resembling a ridge tent were used in Israel to irrigate plants.

Saplings supplied with dew and very slight rainfall from these collectors survived much better than the control group planted without such aids – they all dried up over the summer.

Zibold's condenser had apparently performed reasonably well, but in fact his exact results are not at all clear, and it is possible that the collector was intercepting fog, which added significantly to the yield.

[33] OPUR began a study of dew condensation under laboratory conditions; they developed a special hydrophobic film and experimented with trial installations, including a 30 square metres (320 sq ft) collector in Corsica.

[35] By the time they were ready for their first practical installation, they heard that one of their members, Girja Sharan, had obtained a grant to construct a dew condenser in Kothara, India.

In April 2001, Sharan had incidentally noticed substantial condensation on the roof of a cottage at Toran Beach Resort in the arid coastal region of Kutch, where he was briefly staying.

[38] The plastic film, known as OPUR foil, is hydrophilic and is made from polyethylene mixed with titanium dioxide and barium sulphate.

There are three principal approaches to the design of the heat sinks that collect the moisture in air wells: high mass, radiative, and active.

Early in the twentieth century, there was interest in high-mass air wells, but despite much experimentation including the construction of massive structures, this approach proved to be a failure.

The problem with the high-mass collectors was that they could not get rid of sufficient heat during the night – despite design features intended to ensure that this would happen.

[3] While some thinkers have believed that Zibold might have been correct after all,[41][42] an article in Journal of Arid Environments discusses why high-mass condenser designs of this type cannot yield useful amounts of water: We would like to stress the following point.

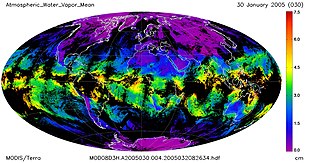

Meteorological data shows that the dew point temperature (an indicator of the water content of the air) does not change appreciably when the weather is stable.

This is why subsequent attempts by L. Chaptal and A. Knapen to build massive dew condensers only rarely resulted in significant yields.

[Emphasis as in original][2]Although ancient air wells are mentioned in some sources, there is scant evidence for them, and persistent belief in their existence has the character of a modern myth.

The condensing surface is backed by a thick layer of insulating material such as polystyrene foam and supported 2–3 metres (7–10 ft) above ground level.

[44] Although other heights do not typically work quite so well, it may be less expensive or more convenient to mount a collector near to ground level or on a two-story building.

This is probably because the designs shield the condensing surfaces from unwanted heat radiated by the lower atmosphere, and, being symmetrical, they are not sensitive to wind direction.

[49][50][51] Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have emulated this capability by creating a textured surface that combines alternating hydrophobic and hydrophilic materials.

[3] The air conditioning system of the Burj Khalifa in Dubai, for example, produces an estimated 15 million US gallons (57,000 m3) of water each year that is used for irrigating the tower's landscape plantings.

For example, in the 1930s, American designers added condenser systems to airships – in this case the air was that emitted by the exhaust of the engines, and so it contained additional water as a product of combustion.

By collecting ballast in this way, the airship's buoyancy could be kept relatively constant without having to release helium gas, which was both expensive and in limited supply.