Al-Andalus

After a decisive victory over King Roderic at the Battle of Guadalete on July 19, 711, Tariq, accompanied by his mawla, governor Musa ibn Nusayr of Ifriqiya, brought most of the Visigothic Kingdom under Muslim rule in a seven-year campaign.

[citation needed] Following the Muslim conquest of Spain, al-Andalus, then at its greatest extent, was divided into five administrative units, corresponding very roughly to: modern Andalusia; Castile and León; Navarre, Aragon, and Catalonia; Portugal and Galicia; and the Languedoc-Roussillon area of Occitania.

To put down the rebellion, the Umayyad Caliph Hisham dispatched a large Arab army, composed of regiments (Junds) of Bilad Ash-Sham,[21] to North Africa.

Berber garrisons in the north of the Iberian Peninsula mutinied, deposed their Arab commanders, and organized a large rebel army to march against the strongholds of Toledo, Córdoba, and Algeciras.

After the rebellious Berber garrisons evacuated the northern frontier fortresses, the Christian king Alfonso I of Asturias set about immediately seizing the empty forts for himself, quickly adding the northwestern provinces of Galicia and León to his fledgling kingdom.

The Asturians evacuated the Christian populations from the towns and villages of the Galician-Leonese lowlands, creating an empty buffer zone in the Douro River valley (the "Desert of the Duero").

These disturbances and disorder also allowed the Franks, now under the leadership of Pepin the Short, to invade the strategic strip of Septimania in 752, hoping to deprive al-Andalus of an easy launching pad for raids into Francia.

But when the Abbasids rejected the offer and demanded submission, the Fihrids declared independence and, probably out of spite, invited the deposed remnants of the Umayyad clan to take refuge in their dominions.

[26] He had fled the Abbasids, who had overthrown the Umayyads in Damascus and were slaughtering members of that family, and then he spent four years in exile in North Africa, assessing the political situation in al-Andalus across the Straits of Gibraltar, before he landed at Almuñécar.

[29] Abd al Rahman's rule was stable in the years after his conquest – he built major public works, most famously the Mosque of Córdoba, and helped urbanize the emirate while defending it from invaders, including the quashing of numerous rebellions, and decisively repelling the invasion by Charlemagne (which would later inspire the epic, Chanson de Roland).

[43] The Caliphate of Córdoba effectively collapsed during a ruinous civil war between 1009 and 1013, although it was not finally abolished until 1031 when al-Andalus broke up into a number of mostly independent mini-states and principalities called taifas.

After 1031, the taifas were generally too weak to defend themselves against repeated raids and demands for tribute from the Christian states to the north and west, which were known to the Muslims as "the Galician nations",[46] and which had spread from their initial strongholds in Galicia, Asturias, Cantabria, the Basque country, and the Carolingian Marca Hispanica to become the Kingdoms of Navarre, León, Portugal, Castile and Aragon, and the County of Barcelona.

[51] After the fall of Toledo, most of the major taifa rulers agreed to request the intervention of the Almoravids, a Berber empire based in Marrakesh that had conquered much of northwest Africa.

Although surrounded by Castilian lands, the emirate was wealthy through being tightly integrated in Mediterranean trade networks and enjoyed a period of considerable cultural and economic prosperity.

Many of the Muslim elite, including Muhammad XII, who had been given the area of the Alpujarras mountains as a principality, found life under Christian rule intolerable and passed over into North Africa.

[86] In 1502 the Catholic Monarchs decreed the forced conversion of all Muslims living under the rule of the Crown of Castile,[87] although in the kingdoms of Aragon and Valencia (both now part of Spain) the open practice of Islam was allowed until 1526.

[91] The earliest evidence of such activities in al-Andalus dates to the reign of Abd ar-Rahman II (r. 822–852), when developments were spurred by exposure to older works translated from, Greek, Persian and other languages.

[93] Other agronomic innovations in al-Andalus include the cultivation of the pomegranate from Syria, which has since become the namesake and ubiquitous symbol of the city of Granada, as well as the first attempt to create a botanical garden near Córdoba by 'Abd al-Rahman I.

[117]Non-Muslims were given the status of ahl al-dhimma (people under protection), with adult men paying a "Jizya" tax equal to one dinar per year with exemptions for the elderly and the disabled.

[132] In the 11th century, the Hindu-Arabic numeral system (base 10) had reached Europe via Al-Andalus through Spanish Muslims, together with knowledge of astronomy and instruments like the astrolabe, which was first imported by Gerbert of Aurillac.

[133] By about 1260, following the Almohad period, most Christians had migrated to the north and Muslim territories in Iberia were reduced to the Emirate of Granada, in which more than 90% of the population had converted to Islam and Arabic-Romance bilingualism seems to have largely disappeared.

Al-Mansur was a distinctly religious man and disapproved of the sciences of astronomy, logic, and especially of astrology, so much so that many books on these subjects, which had been preserved and collected at great expense by Al-Hakam II, were burned publicly.

Maslamah Ibn Ahmad al-Majriti (died 1008) was an outstanding scholar in astronomy and astrology; he was an intrepid traveller who journeyed all over the Islamic world and beyond and kept in touch with the Brethren of Purity.

Poets and commentators like Judah Halevi (1086–1145) and Dunash ben Labrat (920–990) contributed to the cultural life of al-Andalus, but the area was even more important to the development of Jewish philosophy.

Its key features include a hypostyle hall with marble columns supporting two-tiered arches, a horseshoe-arch mihrab, ribbed domes, a courtyard (sahn) with gardens, and a minaret (later converted into a bell tower).

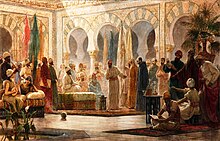

[159]: 79 The official workshops of the Caliphate, such as those at Madinat al-Zahra, produced luxury goods for use at court or as gifts for guests, allies, and diplomats, which stimulated artistic production.

[165]: 361–368 [170] Among the most famous examples is the Alcázar of Seville, the former Abbadid and Almohad palace redeveloped by Christian rulers such as Peter of Castile, who in 1364 started adding new Moorish-style sections with the help of Muslim craftsmen from Granada and Toledo.

Evidence includes the behaviour of rulers, such as Abd al-Rahmn III, Al-Hakam II, Hisham II, and Al Mu'tamid, who openly kept male harems; the memoirs of Abdallah ibn Buluggin, last Zirid king of Granada, makes references to male prostitutes, who charged higher fees and had a higher class of clientele than did their female counterparts: the repeated criticisms of Christians; and especially the abundant poetry.

[199] Jawaris concubines who gave birth to a child attained the status of an umm walad, which meant that they could no longer be sold and were to be set free after the death of her master.

[citation needed] Scientists and philosophers such as Averroes and Al-Zahrawi (fathers of rationalism and surgery, respectively) heavily inspired the Renaissance, and their ideas are still world renowned to this day.